Japanese boxing has drawn global attention more than ever before.

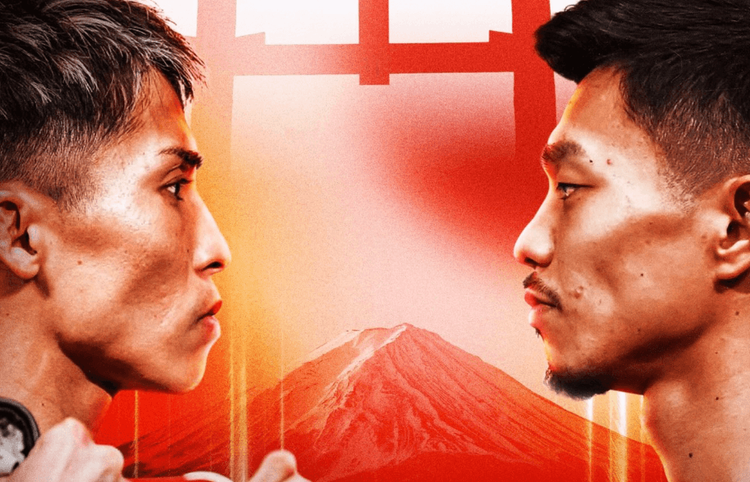

Boxing fans in every corner of the world may talk about how great Naoya Inoue, The Ring’s super bantamweight champion, is, or may debate about who will win his anticipated match with younger star Junto Nakatani.

The biggest all-Japanese fight in history is expected to be set at Tokyo Dome in May 2026.

First, Inoue (31-0, 27 KOs) must defend all of his belts against WBC’s top-rated challenger David Picasso of Mexico, and Nakatani (31-0, 24 KOs) has to overcome another Mexican world-rated fighter in Sebastian Hernandez at “The Ring V: Night of the Samurai” scheduled at Mohammed Abdo Arena in Saudi Arabia on December 27.

Twenty years ago, no one in Japan probably could imagine that such an era would come in boxing.

Two undefeated boxers from the Far East island country are near the top of The Ring’s pound-for-pound rankings, where Inoue, who has become undisputed champion across two weight divisions, has long been in the top-three discussions.

He became the first Japanese fighter in The Ring’s history to be No. 1 on the list, and the first Asian since Manny Pacquiao, following a superb KO win over a legend Nonito Donaire in June 2022.

Nakatani, who won world titles in three divisions including the WBO/IBF unified bantamweight championship, has been climbing the ranks since he was installed at No. 10 after he snatched the WBC belt, his third weight divisions for world titles, from Mexico’s Alejandro Santiago in February 2024. Nakatani is now seventh.

It may be widely known that a hard-working and tough-minded culture has bred boxing talent in Japan, but it’s not by chance that great genius in Inoue and Nakatani has emerged onto a world stage.

How did it happen?

Not a coincidence

Inoue and Nakatani share one common origin: Both came up through an annual kids’ competition, the U-15 National Championship, that Japan Pro Boxing Association started organizing alongside JBC Japan Boxing Commission.

At 15, Inoue was the MVP in the inaugural tournament in 2008. Nakatani became two-time champion five years later. Brothers Naoya and Takuma, Yudai and Ginjiro Shigeoka and Hayato and Reito Tsutsumi, ambassadors for The Ring today, also stood out in that kids’ program.

Not like in the other countries such as America or Mexico, boxing had not been recognized in general as a sport for young children in Japan. The majority of past professional boxers participated as a second or third sport after school age.

Choosing boxing was the best chance to be a professional athlete. Amateur experience wasn’t mandatory, and a strong will — coupled with membership to a boxing stable registered with JPBA — was the only requirement to start. People love the incredible story of “Man on Fire” Koichi Wajima, multiple-time Ring junior middleweight champion in 1970s who made his debut at 25 after running into a boxing gym in Tokyo when he was just a workman away from his rural home in Hokkaido.

There has never been a ban on children, and there were superb world champions in previous century such as Shozo Saijo, Hideyuki Ohashi (manager of Naoya Inoue), Joichiro Tatsuyoshi, Hiroshi Kawasima, Keitaro Hoshino, Hozumi Hasegawa and more who found their ways in boxing before their teenage years. In reality, you might have seen young kids training in local boxing gyms. Yet, there was no competition to motivate them to showcase their progress.

Around 2000, some unofficial sparring meetings in gyms in Osaka, Yokohama and other locations started voluntarily, which led to the JPBA and JBC organize a national tournament categorized by age and weight seven years later, for ages 10-15. They had to wait to be ranked until joining high school teams to compete. Before, it was common to start amateur boxing in high school and with college teams.

The inaugural National U-15 Tournament was held at Korakuen Hall in Tokyo in August 2008 and it showed high quality of competitors from regional qualifiers. Inoue was one of them, but he already had been well-known as a phenom in unofficial local sparring meetings.

Nakatani won in the tournament in 2011 and ‘12 before setting off to work with Rudy Hernandez in Los Angeles in 2013.

The annual championship staged at the famous Korakuen Hall has been the goal of boys and girls. The new gateway to future world champions kept growing under a new name, “Junior Champions League,” adding an international version, “Naoya Inoue Cup,” recently.

The new generation that looks up to Inoue and Nakatani is steadily growing up in that system.

All eyes on Inoue

The structural reform is feeding the health of the boxing scene, though the industry is still struggling to secure its future. The numbers of licensed professional boxers and fights decreased in the past 20 years, according to JBC. The declining birth rate in general is likely one factor, but the drop of boxing population is particularly noticeable here.

In 2006, there were 3,220 pro licensed boxers, including eight world champions and 303 shows nationwide. Both numbers kept shrinking to 2,068 boxers and 177 shows in 2019. In 2020, it was an anomaly because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Numbers were down to 1,417 boxers (no licensing of foreign boxers) and 92 shows.

Some promoters say matchmaking is still not easy, especially for four-rounders, but the numbers have recovered to 2,106 boxers and 195 shows to surpass 2019.

And there is a glimmer of hope for the boxing world.

Inoue has been named one of the most liked sports stars, according to the biennial survey since 1992 on sports popularity targeting 3,000 people ages 18 and over, according to the Sasakawa Sports Foundation, a public interest foundation. Inoue ranked fourth in 2022, marking his first top-10 ranking of all athletes no matter of nationality, active or retired, in the survey.

And he climbed to No. 3 in the 2024 survey, following Major League Baseball MVP Shohei Ohtani, who won a record 41% of vote, and No. 2 Yuki Ishikawa, a professional volleyball player who is a member of Sir Safety Perugia competing in Italian Serie A, and above Ichiro at No. 4 who would be a first MLB Hall of Famer from Japan next year.

In another annual research on popular athletes by Central Research Agency since 1994, Inoue, the only boxer, has been ranked seventh three years in a row since 2023. The boxing world has to be proud to have a national sport hero to keep the recognition in Japan as a sport.

If “Night of the Samurai” in Saudi Arabia, the first Ring event featuring Japanese top boxers, is successful, 2026 should give us an all-Japanese dream match, Inoue vs Nakatani.

It will be the biggest showdown in Japanese boxing history at Tokyo Dome, the nation’s mecca of entertainment.

People talk about it. Young people talk about it at schools, too.

It can be a game-changer for the sport here.