The goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) is among the most unusual and least understood predators in the ocean. Deep-dwelling, rarely encountered, and visually distinctive, the species has drawn interest for its anatomical oddities. Now, new research has confirmed that it possesses one of the fastest jaw mechanisms ever recorded in fish.

In recent years, scientists analysing rare deep-sea footage uncovered a feeding method so rapid and specialised that it required new classification. This behaviour, now termed slingshot feeding, enables the goblin shark to strike prey at high velocity without using speed or momentum from its body. The finding addresses long-standing questions about how large, slow-moving predators succeed in energy-scarce environments.

The results, based on footage captured by the Okinawa Churashima Foundation and studied by researchers at Hokkaido University, show the shark’s jaws launching forward at a speed of 3.1 metres per second. The strike reaches nearly 10 percent of the animal’s body length and allows it to capture prey that would otherwise be out of reach. The mechanism is the fastest jaw protrusion documented among sharks and one of the most extreme in all fish.

First described in 1898, the goblin shark remained biologically elusive due to its habitat, which ranges from 250 to over 1,200 metres deep. New data now position this shark as a key species for understanding the mechanics of predation in extreme marine environments.

Fastest Jaws in the Ocean

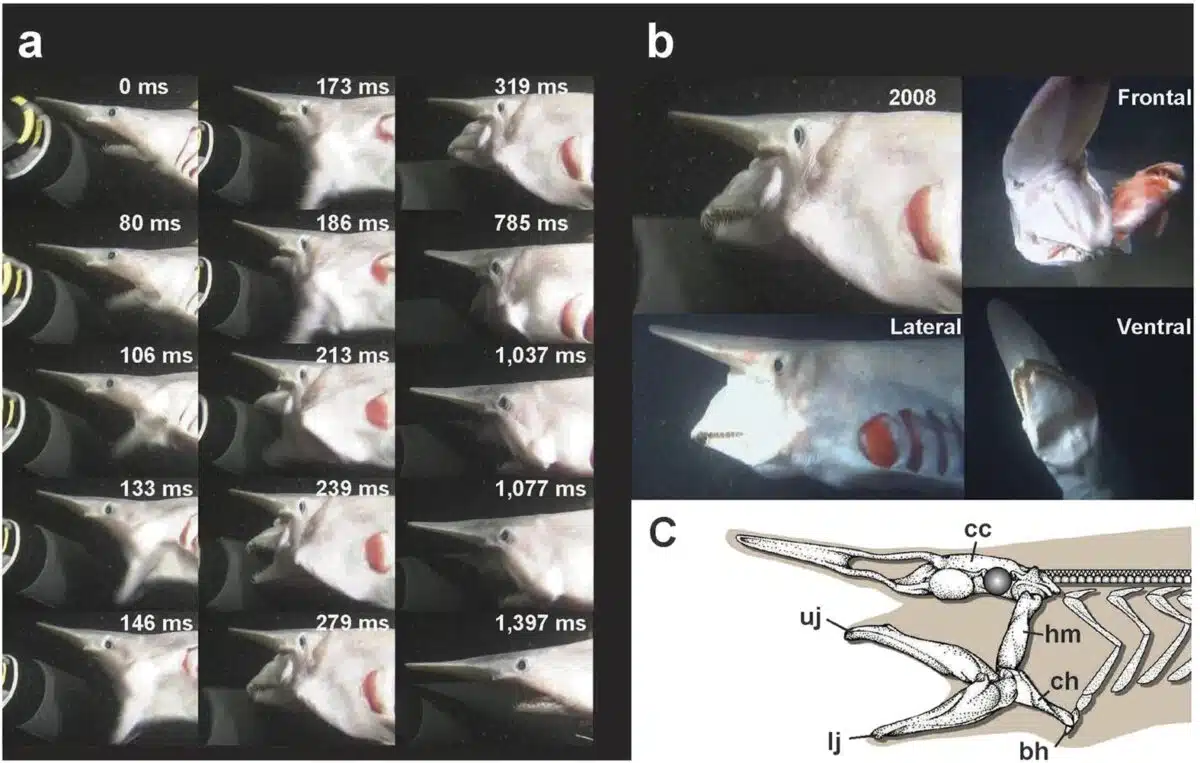

A peer-reviewed study in Scientific Reports analysed high-speed video of five successful feeding strikes by two individual goblin sharks. Researchers observed that the animal’s jaws could project forward in a rapid, staged sequence. The sequence includes initial mouth opening, jaw projection, fast closure, and a secondary open-close movement during retraction.

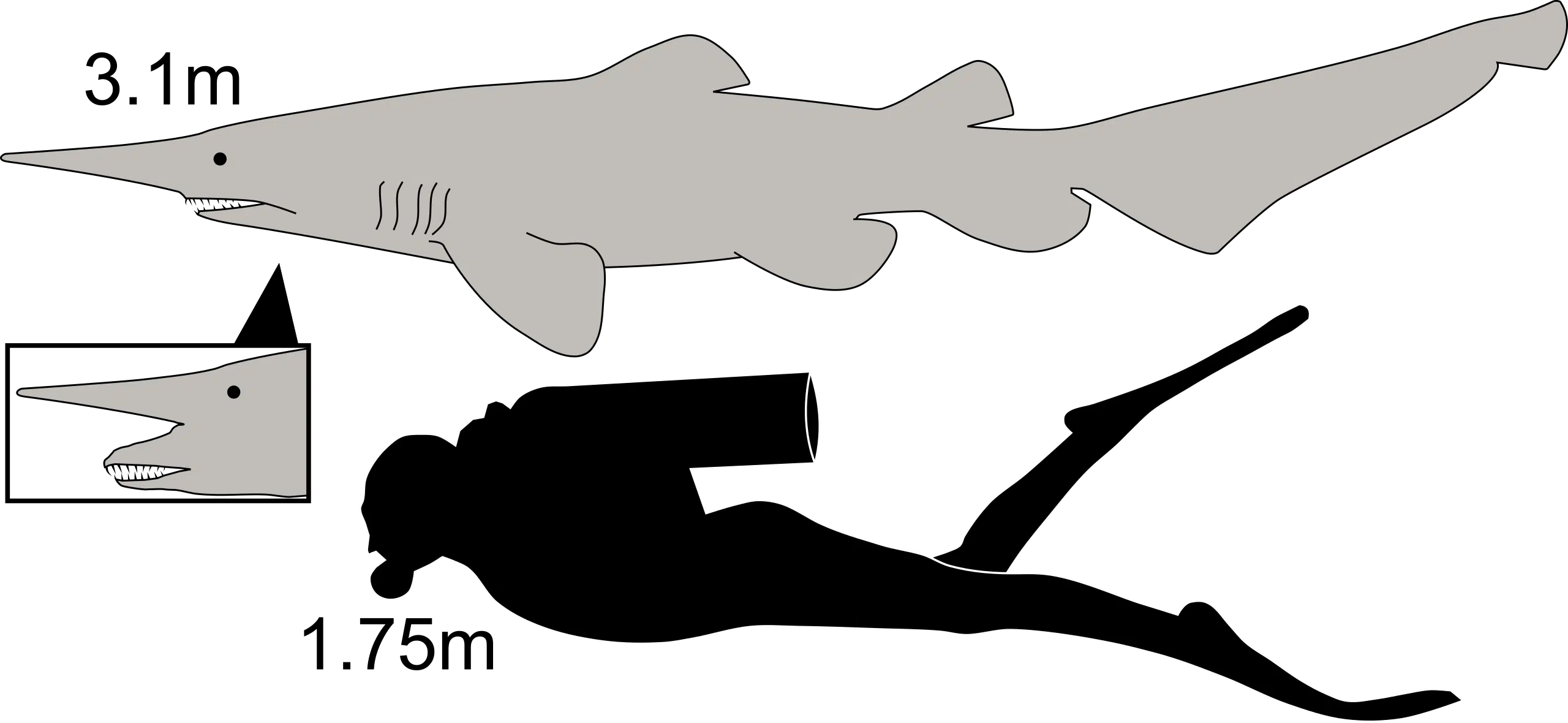

Goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) scaled with a human. Credit: Kurzon, CC BY-SA 3.0

Goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) scaled with a human. Credit: Kurzon, CC BY-SA 3.0

The strike speed of 3.1 metres per second surpasses all previously recorded jaw movements in fish. The total jaw extension reached 8.6 to 9.4 percent of body length, well beyond the 1 to 2 percent typically observed in other shark species. These metrics were captured from live feeding observations rather than dissection or modelling, providing rare behavioural confirmation.

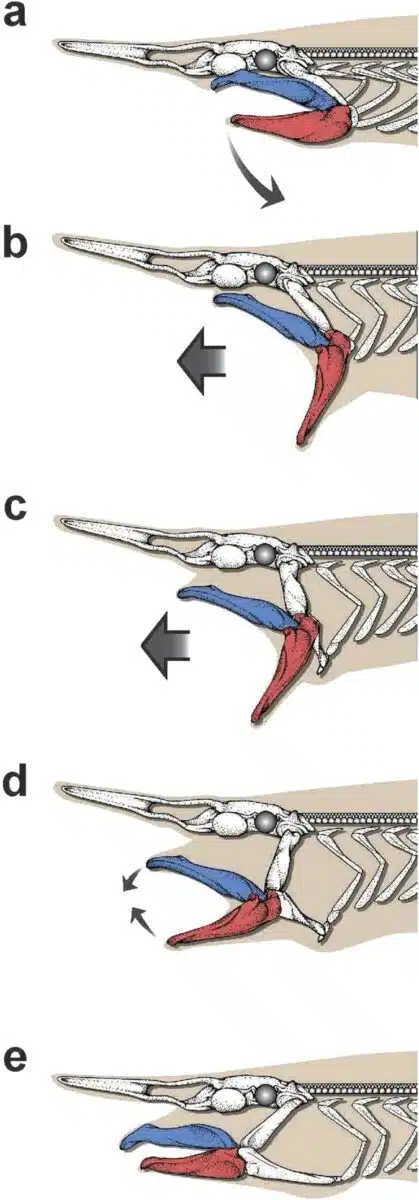

Researchers identified specialised ligaments in the jaw structure that store energy and release it during the strike, functioning similarly to a stretched elastic band. The structure enables a high-energy output without requiring significant movement from the rest of the body.

Video stills of a goblin shark eating show its protruding jaws (elapsed time is shown in milliseconds). Credit: NHK Illustrations/Hokkaido University

Video stills of a goblin shark eating show its protruding jaws (elapsed time is shown in milliseconds). Credit: NHK Illustrations/Hokkaido University

The study also noted an unexplained secondary mouth movement during jaw retraction. No definitive explanation has been given, and the function of this motion remains a subject for further investigation. A summary of the research is available via EurekAlert, the science news platform associated with the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Adaptation to Energy-Poor Environments

The goblin shark’s slow movement is consistent with its deep-sea habitat. It inhabits a zone where water pressure is high, temperatures are low, and food availability is limited. Energy conservation is critical to survival. The shark uses minimal body motion between meals, relying on its slingshot jaws to complete fast strikes with little warning.

Slingshot feeding of the goblin shark. (a) Resting phase; (b) peak retraction; (c) shooting stage; (d) onset of grasping stage; (e) peak protrusion. Thick arrows indicate movements of jaws and thin arrows indicate movements of upper and lower jaw cartilages. Credit: NHK Illustrations/Hokkaido University

Slingshot feeding of the goblin shark. (a) Resting phase; (b) peak retraction; (c) shooting stage; (d) onset of grasping stage; (e) peak protrusion. Thick arrows indicate movements of jaws and thin arrows indicate movements of upper and lower jaw cartilages. Credit: NHK Illustrations/Hokkaido University

As outlined by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the goblin shark exhibits a slow, energy-efficient swimming style that aligns with its environment. Its anatomy supports near-neutral buoyancy through high concentrations of low-density fatty acids in muscle and liver tissues. Combined with a long tail and extended upper caudal fin, the species is built for sustained, low-energy movement.

Rather than pursuing prey over long distances, goblin sharks employ an ambush strategy. This model proves effective in deep ocean conditions and contrasts with the faster, more aggressive tactics used by shallow-water species like the great white or mako shark.

Electrosensory Precision

The goblin shark’s elongated snout contains a dense array of ampullae of Lorenzini—electroreceptors that detect electrical signals generated by the movement of nearby animals. These sensors give the shark a distinct advantage in darkness, allowing it to locate prey even in conditions of near-zero visibility.

The Australian Museum reports that the underside of the snout is heavily pored, indicating high sensitivity. While many sharks possess similar sensory capabilities, the goblin shark’s configuration is exceptionally concentrated, helping it track squid, fish, and crustaceans in low-light environments.

Its feeding strategy aligns closely with its morphology. The mouth retracts beneath the eye when not in use, maintaining a streamlined profile. When extended, the jaws change the shark’s silhouette entirely, revealing rows of narrow, pointed teeth adapted for gripping soft-bodied prey. Field studies in Japan have documented the presence of bony fishes and squid in the stomachs of goblin sharks, supporting a generalist diet across the benthic food web.

Limited Visibility, High Scientific Value

Goblin sharks are rarely observed in the wild. Most of what is known about them has come from incidental deep-sea bycatch. The species has been documented in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, including off the coasts of Japan, South Africa, and Australia. Their global distribution remains poorly understood due to limited access to their deep habitats.

As noted by researchers in the original study, goblin sharks belong to an ancient family, Mitsukurinidae, which dates back over 125 million years. They are the only living representative of this lineage, making them an important reference point for understanding shark evolution and deep-sea adaptation.

Despite their appearance, there are no verified instances of goblin sharks interacting aggressively with humans. Their deep-sea location and low abundance reduce the chance of contact. The species remains understudied, with significant gaps in knowledge about reproduction, population size, and vulnerability to environmental change.