During the dry season, a shallow Amazon lake warmed to about 106 degrees Fahrenheit (41 degrees Celsius). Within days, over 100 river dolphins died from the heat and washed ashore around Lake Tefe in Brazil, shocking communities that depend on those waters.

A new study of ten central Amazon lakes found that a drought and heat wave pushed water temperatures to record levels.

Brazilian hydrologist, Ayan Santos Fleischmann, studies water systems, and led the field investigation at Lake Tefe.

His research focuses on how Amazon lakes respond to extreme heat and drought, and how those changes affect wildlife.

During the event, Lake Tefe lost roughly three-quarters of its surface area, leaving a shallower basin that heated faster.

Measurements showed that the remaining water was only about two meters deep, and almost equally hot from surface to bottom.

River dolphins and lake heat

The Amazon river dolphin, or boto, is a freshwater cetacean adapted to life in murky rivers rather than oceans.

Conservation assessments list this species as endangered, with declining populations. Species profiles highlight threats from fishing, dams, and pollution.

Smaller tucuxi dolphins share many of the same channels and prey, yet they travel in larger, faster-moving groups than botos.

Researchers now classify tucuxis as endangered too, after sustained declines across the Amazon basin documented by dedicated dolphin-monitoring programs.

During the Lake Tefe crisis, roughly 150 river dolphins were found dead within a single week. Researchers reported that the water was so hot it was painful to touch, even briefly.

Scientists say tropical lakes have been far less monitored than temperate ones, even though millions of people depend on them daily.

Events like this one at Lake Tefe reveal that these supposedly stable systems can cross dangerous thresholds very quickly. This is especially true when heat and drought coincide.

Large temperature swings

The researchers also measured daily temperature swings of about 23 degrees Fahrenheit (13 degrees Celsius) between afternoon peaks and the coolest pre-dawn hours.

Rapid swings like that can be as stressful as constant heat, because fish and river dolphins struggle to adjust their metabolism.

During two weeks of extreme conditions, animals in Lake Tefe faced repeated thermal shocks with little chance to find cooler refuge.

Such patterns are expected to become common as ongoing climate change and gradual warming of weather patterns adds heat to the atmosphere.

Red lake and empty nets

The river dolphin deaths drew headlines, but thousands of fish also died as hot, stagnant water lost essential oxygen.

Researchers documented a phytoplankton bloom, a rapid increase in microscopic algae, that turned parts of Lake Tefe reddish.

For families who depend on fish for protein and income, nets came back nearly empty while rotting carcasses fouled the shoreline.

Some travel routes by boat also became impassable as channels dried or filled with stranded logs, adding hours to trips.

Decades of warming in Amazon lakes

To see whether the event was unusual, the team analyzed satellite records back to 1990 and tracked surface temperatures across Amazon lakes.

They found that lakes have warmed by roughly 1.1 degrees Fahrenheit (0.6 degrees Celsius) per decade. This is faster than in many other regions.

Years with extreme warmth appear more often in the record, and several align with droughts that lowered water levels in the basin.

If greenhouse gas emissions keep rising, similar hot-tub-style events could occur often and affect other Amazon floodplain lakes.

Drought and heat team up

A broad research review of temperate rivers shows that drought-driven low flows often coincide with extreme water temperature spikes.

Low flows mean less water is available to absorb incoming heat. The same amount of sunlight can therefore cause higher temperatures.

In Lake Tefe, drought concentrated heat, sediments, and pollutants into a smaller volume of water. This increased stress on animals that were already near their limits.

Calmer winds during the event reduced mixing and evaporative cooling, so the lakes behaved like stagnant pools rather than moving rivers.

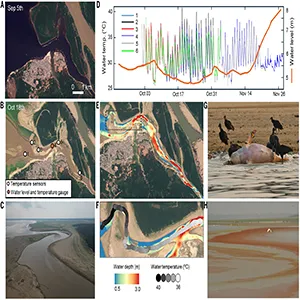

Image montage showing major drought and heating of Tefé Lake waters in 2023, reaching >40°C in the entire water column at the monitoring site, resulting in the death of over 100 river dolphins. Credit: Science. Click image to enlarge.River dolphins are revered

Image montage showing major drought and heating of Tefé Lake waters in 2023, reaching >40°C in the entire water column at the monitoring site, resulting in the death of over 100 river dolphins. Credit: Science. Click image to enlarge.River dolphins are revered

For many Amazonian communities, river dolphins are seen as guardians of the rivers and woven into local stories and ceremonies.

Seeing their bodies line the shore brought grief and anxiety to many. Some elders expressed a sense that natural protections were disappearing.

Fish die-offs forced families to buy more expensive food in town or rely on emergency deliveries, straining budgets already hit by the drought.

Health workers also worried about contamination from decaying animals, since people bathe in and drink from the same waters.

Warning sign for climate goals

All five river dolphin species are now considered threatened with extinction, according to the WWF.

For species like the tucuxi, which is already classified as endangered, additional losses from single extreme events can erase decades of slower decline.

Episodes where entire lakes approach hot-tub temperatures also signal that climate impacts are hitting ecosystems harder and earlier than many models predicted.

If current climate pledges are not strengthened and implemented, similar losses could become a regular feature of life in many river basins.

Climate, heat, and river dolphins

Researchers working in the region argue that better monitoring networks, shared openly, can give communities earlier warnings when lakes begin to overheat.

Some teams are exploring measures like protecting surrounding forests, restoring floodplains, and adjusting reservoir releases to create cooler refuge zones during intense heat.

Others emphasize that involving Indigenous peoples and long-term riverine residents in decision-making ensures that scientific plans reflect local knowledge and priorities.

“The climate emergency is here, there is no doubt about it,” said Fleischmann, who hopes the study will influence future climate decisions.

The study is published in Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–