Cameras may soon see without lenses, and the change could be as profound as the leap from film to digital.

A new imaging technology developed at the University of Connecticut promises to rewrite the rules of optical imaging, enabling ultra-high resolution views without relying on bulky lenses or painstaking physical alignment.

Instead, the system leans on computation, sensor arrays, and clever math to overcome limits that have constrained optics for decades.

The breakthrough comes from Professor Guoan Zheng’s lab, where researchers drew inspiration from an unlikely source, the Event Horizon Telescope, the global radio telescope array that captured the first-ever image of a black hole.

That system stitched together data from multiple telescopes to simulate a much larger one.

But translating that idea to visible light has long seemed impractical. Optical wavelengths are far shorter than radio waves, meaning even tiny misalignments between sensors can destroy image quality.

Until now, synchronizing optical sensors with nanometer precision has been a nearly impossible task.

Zheng and his team took a different approach, sidestepping physical synchronization altogether.

Imaging without lenses

The result is the Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager, or MASI. Rather than forcing sensors to operate in perfect lockstep, MASI allows each one to measure light independently.

Computational algorithms then synchronize the data afterward, reconstructing a single, coherent image.

“At the heart of this breakthrough is a longstanding technical problem,” said Zheng.

“Synthetic aperture imaging – the method that allowed the Event Horizon Telescope to image a black hole – works by coherently combining measurements from multiple separated sensors to simulate a much larger imaging aperture.”

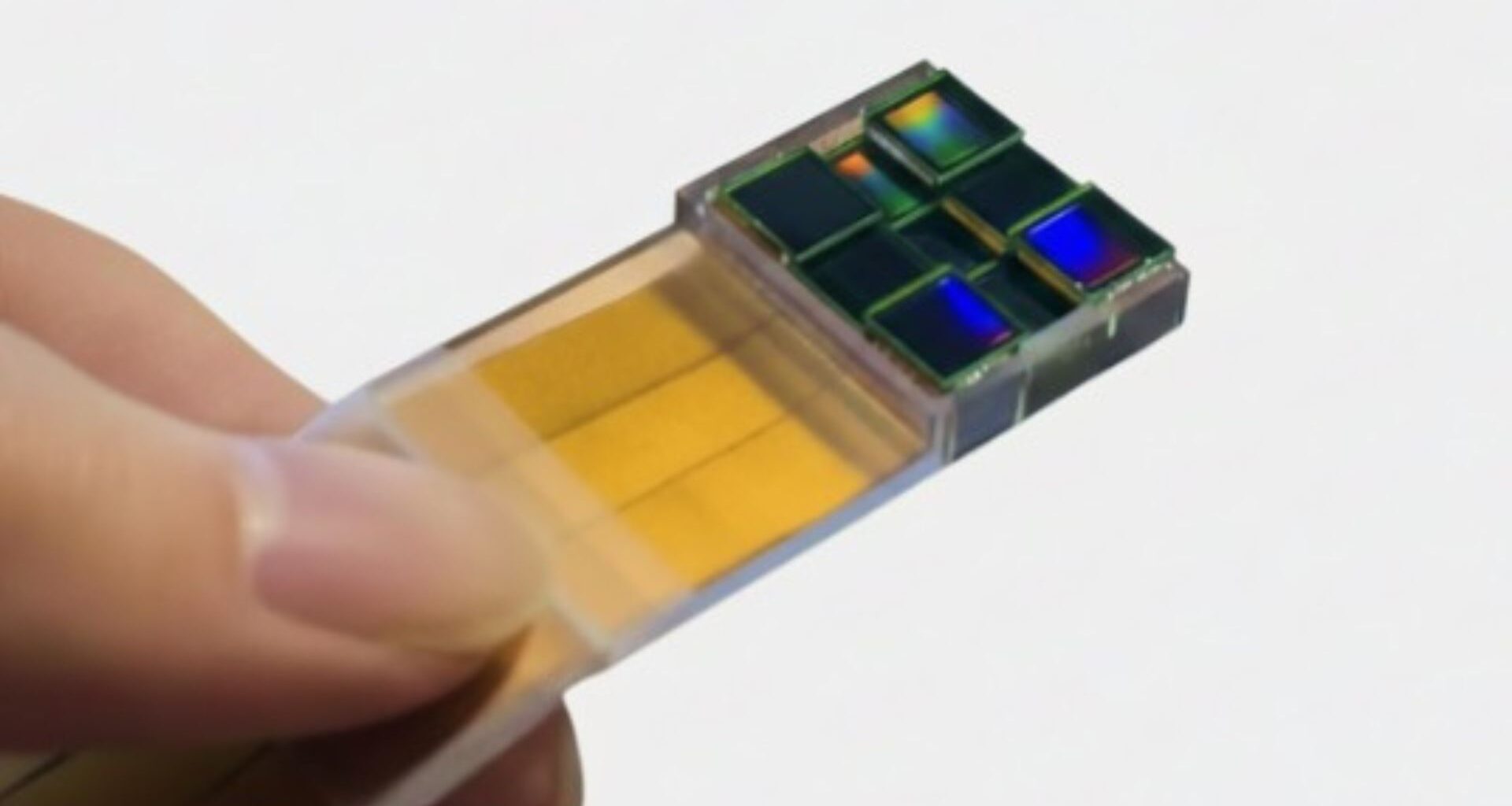

MASI replaces lenses with an array of coded sensors positioned at different points in a diffraction plane.

Each sensor captures raw diffraction patterns that contain both brightness and phase information about the light interacting with an object.

Those measurements are processed to recover each sensor’s complex wavefield. The wavefields are then digitally padded and numerically propagated back to the object plane.

A computational phase synchronization method iteratively aligns the data, maximizing coherence across the combined image.

This software-driven synchronization eliminates the rigid interferometric setups that have blocked practical optical synthetic aperture systems for years.

The outcome is a virtual aperture far larger than any individual sensor.

Software replaces glass

The payoff is striking. MASI can achieve sub-micron resolution across a wide field of view, all without lenses and from working distances of several centimeters.

Conventional optics typically force trade-offs between resolution, field of view, and distance from the object.

The system’s capabilities were demonstrated by imaging a bullet cartridge, capturing micrometer-scale details such as the firing pin impression.

Such markings can be used to link ammunition to a specific firearm, highlighting potential forensic applications.

“The potential applications for MASI span multiple fields, from forensic science and medical diagnostics to industrial inspection and remote sensing,” said Zheng. “But what’s most exciting is the scalability.”

Unlike traditional optical systems, which become exponentially more complex as they grow, MASI scales linearly.

Adding more sensors increases capability without introducing prohibitive alignment challenges.

Beyond imaging, the work underscores a broader shift in engineering: using computation to bypass physical constraints once thought fundamental.

By decoupling measurement from synchronization, MASI opens a new domain where software, not glass, defines what optical systems can see, according to findings published in Nature Communications.

With over a decade-long career in journalism, Neetika Walter has worked with The Economic Times, ANI, and Hindustan Times, covering politics, business, technology, and the clean energy sector. Passionate about contemporary culture, books, poetry, and storytelling, she brings depth and insight to her writing. When she isn’t chasing stories, she’s likely lost in a book or enjoying the company of her dogs.