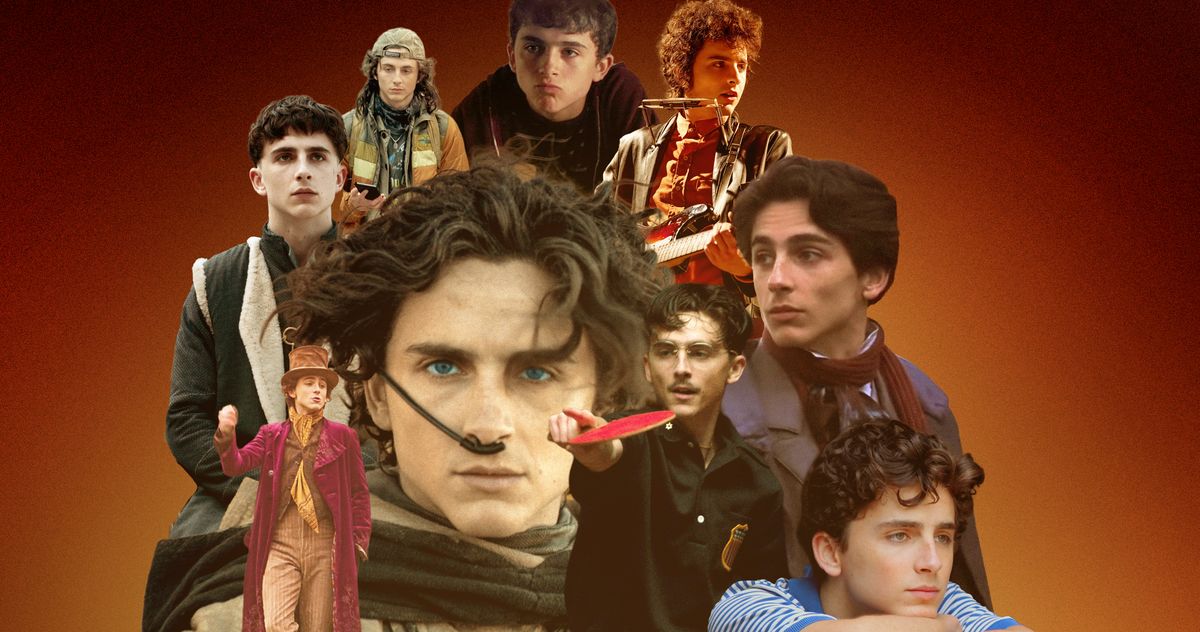

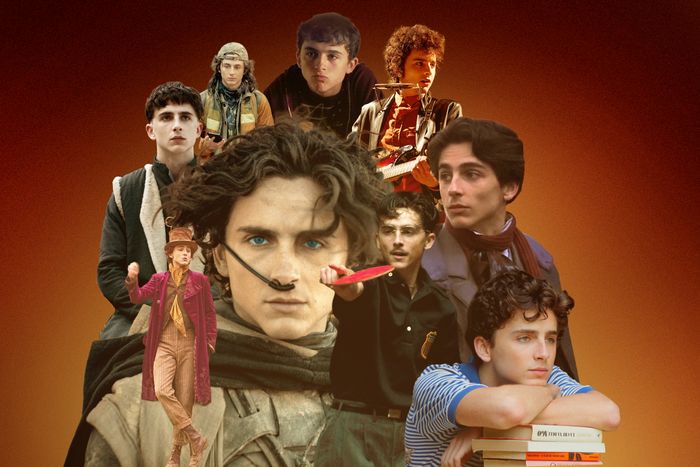

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Sony Pictures, Warner Bros., A24, Searchlight, Netflix, Paramount

Timothée Chalamet is brat, in the most complimentary way possible. In only 11 years of film performances, Chalamet’s bulldozed his way to the forefront of his generation, worked with some of this era’s most respected filmmakers, and received two Academy Award nominations for Best Actor. He’s probably going to get a third one for Marty Supreme, the press tour of which has Chalamet going everywhere and doing everything; the film is already doing bananas box-office numbers for A24. All of this is to say, Chalamet has the exact presence that Charli XCX was describing in her 2024 album — a mixture of attitude, gumption, and ambition that has superpowered his career from no-dialogue parts in myriad indies to anchoring the multibillion-dollar Dune franchise. So, it’s time to rank Chalamet’s performances, and the movies they’re in.

As with all Vulture rankings, the order here is determined by both a critique of the movies themselves and Chalamet’s turn within them. We’re excluding Chalamet’s TV work — although there isn’t that much of it anyway, aside from his foundationally dickish supporting role on Homeland — and focusing instead on the big-screen casting that has helped propel him to the upper tier of young actors working today. Chalamet’s older than you might think (born in 1995, he’s technically a baby millennial rather than Gen Z), but his career is still only in its early years. Unless he gives it all up for a secret rap career, we’ve got a lot more time with Chalamet’s specific brand of onscreen impishness. Let’s assess.

Photo: Paramount Pictures

Timmy’s first movie, and he’s barely in it. Sandwiched in between Jason Reitman’s two exceptional films with Charlize Theron, Young Adult and Tully, Men, Women & Children was Reitman’s attempt at timely social analysis — a portrait of how social media and technology are changing how people, especially teens, live. That’s well-intended enough, but the movie itself is a snooze. In Chalamet’s one major scene, he bullies an overprotected classmate played by Kaitlyn Dever and then gets his ass beat by her boyfriend, played by Ansel Elgort. Admittedly, the image of Elgort’s Tim suplexing Chalamet’s Danny onto a cafeteria lunch table is so abrupt that it’s unintentionally hilarious. Otherwise, there’s nothing here.

A similarly forgettable early role, this time in an indie dramedy about childhood best friends whose relationship is tested when Jake (Richard Tanne) is hit by a car and asks for his old buddy Sam (Noah Barrow) to help care for him; unsurprisingly, their feelings for a girl from their past get in the way. Chalamet has a few scenes as the younger Jake. He wears glasses and is kind of dorky. That’s about it.

Another one from Chalamet’s early indies era, One & Two has a fascinating central premise that can’t quite survive a feature-length run time. Chalamet and Kiernan Shipka play siblings Eva and Zac, who have a loving relationship with their mother Elizabeth (Elizabeth Reaser) and an awful relationship with their father Daniel (Grant Bowler). Eva and Zac can teleport, an ability their dad tries to punish out of them by nailing them to walls so they can’t escape; the film follows the siblings as they deal with Daniel’s abuse. This is an early glimpse into Chalamet’s ability to play both bratty and righteous, a combination that he’ll return to over and over again throughout his career. Shipka has the larger role as the more rebellious Eva, though, and it’s more her movie than his.

Photo: Jessica Miglio/Gravier Productions/Everett Collection

One ugh after another: Chalamet plays a character named Gatsby who loves New York; Elle Fanning and Selena Gomez are his two love interests who represent different kinds of art, and therefore different kinds of life, but are of course both besotted with Gatsby; there are random lines of dialogue insulting Afghans and Yasser Arafat. It’s a Woody Allen movie that sat on the shelf for years. It’s dreck. Sorry, Timmy, but what the hell, man?

It’s really a sign of how awful A Rainy Day in New York is that The Adderall Diaries, in which Chalamet has very little dialogue while playing the teen version of troubled author Stephen Elliott (James Franco), is ranked higher on this list. Pamela Romanowsky’s adaptation of Elliott’s actual memoir is incredibly jarringly edited (purposefully, to a degree, to mimic the impact of Elliott’s drug use and spotty memory), but in the flashback sequences featuring Chalamet, he gets to be physical in a way his earlier roles hadn’t allowed for. He gets high, he gets in fights, he shoplifts, he smashes up his negligent father’s (Ed Harris) car; Chalamet throws his body into all of it. Throughout the rest of his career, Chalamet will get increasingly good at explosive bursts of violence to demonstrate his character being up against the edge psychologically and emotionally, and that ability traces back to The Adderall Diaries.

There’s a kind of movie that mistakes having a sprawling ensemble of recognizable faces as having a plot or a point — New York, I Love You; Amsterdam; Mother’s Day — and Love the Coopers is firmly in that subgenre. It’s not good, a mess of Steve Martin narration, tired holiday clichés, and barely sketched characters. Chalamet’s not working with a lot as Charlie, who’s struggling with his parents’ divorce and tripping over himself when trying to approach his crush, Lauren (Molly Bloom). The character is basically “horny lonely teenager stares at his peer’s boobs and somehow she falls for him.” However! Aside from Interstellar, this is Chalamet’s first role in which he gets to do something, whether that’s bickering with Ed Helms and Alex Borstein as his parents or awkwardly flirting with Lauren. (And later, licking her tongue in front of his family.) In his best scene, Chalamet wanders through the Christmas store where Lauren works while amping himself up to talk to her, and he imagines all the decorations and tchotchkes in the store as judging him. His suspicious, indignant, and shocked reactions to the decorations’ frowns, smirks, and raised eyebrows finally give Chalamet the chance to actually build a character rather than exist purely in flashbacks or montages. Even though the role is just an annoying teen boy, we’re beginning to see what Chalamet can do.

This cast! Christian Bale, Jesse Plemons, Rosamund Pike, Wes Studi, Q’orianka Kilcher, Adam Beach, Stephen Lang, and … well, and Chalamet is also there. Scott Cooper’s film about a group of soldiers, led by Bale’s U.S. Army captain Joseph Blocker, tasked with transporting a Cheyenne war chief (Studi) and his family back to Montana, tries its best to do a neo-western thing by pointing out that all kinds of people in the Old West were violent and ruthless. It’s well-intentioned, it’s well-made, and it’s also pretty low down on this list — despite its pedigree — because Chalamet’s role in it is so small. As the French-speaking Private Philippe Dejardin, Chalamet has one conversation with Bale’s Blocker and one major scene where he helps stand guard over Pike’s widow, Rosalee Quaid, as she digs her family’s graves, before he becomes the first of Blocker’s group to get killed off by a raiding Comanche party. It’s not a lot, but it gives us a sneak peek into Chalamet’s ability to work within a hierarchy (Dune and The King will blossom this further), and he gets to employ a cute little French accent. Plus, his death scene is pretty solid! He writhes well!

Photo: A24/Everett Collection

A movie that’s more pastiche than original work, Hot Summer Nights happens to be one of Chalamet’s first lead roles, and he acquits himself just fine. (This was filmed in 2015 but not released broadly by A24 until three years later.) In Elijah Bynum’s neo-noir, Chalamet plays Daniel, a teenager who moves to Cape Cod after his father’s death and becomes an unexpected local legend. The script requires Chalamet transform from awkward kid falling on the floor after a too-deep bong hit to a powerful drug dealer over the course of a summer, and Chalamet uses his late-bloomer qualities (that gangly frame, that youthful face) particularly well to emphasize the former. The film’s narrator describes Daniel’s circumstances, fears, and desires, which undercuts Chalamet a bit by essentially taking some shortcuts with the character’s internal life. Chalamet begins to nail down his niche of ambitious adolescent upstart in this movie, though, and he sells the character’s spontaneity, whether he’s impetuously kissing McKayla (Maika Monroe), the hottest girl in town, or trying to negotiate with the dangerous dealer Dex (Emory Cohen, great).

Finally, we’re starting to get into the really promising stuff. Filmmaker Julia Hart pulled from her own experiences as a teacher for her directorial debut, which stars Lily Rabe as a high-school English teacher, Rachel Stevens, who gets a little too close with one of her students, Billy (Chalamet). The relationship isn’t physical but emotionally compromised; Billy stops taking his medication for his behavioral disorder, ingratiating himself into Rachel’s life and making her feel personally responsible for his personal well-being and his academic potential. Chalamet is great at this kind of character in particular: a young man who is pushing too much and refusing to understand why someone would rear back from that instead of embracing it. His Death of a Salesman monologue, delivered directly into the camera, has such aching, vulnerable energy that you almost feel like you’re spying on a religious confessional.

I’ve already explained my issues with Dune: Part Two, and they boil down to this: Paul’s growth into a villain doesn’t work when Denis Villeneuve strips so much of the purposeful religious and cultural context from the book, and Chalamet’s performance suffers because of it. Although Chalamet is handed a lot of things he is particularly well-suited for — a big pump-up speech, lots of plaintive gazing — he feels like he’s floating through a movie that’s pushing and pulling in too many directions at once. And as my colleague Alison Willmore wrote in her review, Dune: Part Two is really Zendaya’s movie, since Chani’s reactions to Paul’s arc are so much more engrossing than anything the Atreides princeling gets up to. Don’t worry, Villeneuve-heads, the first Dune is way higher up.

Photo: Paramount

There are many things to admire, even love, about Christopher Nolan’s ode to girl dads all throughout space and time, but there is one line that lives in my mind rent-free: Chalamet’s deadpan “No such thing as ghosts, dumbass” to his genius younger sister, Murph (Mackenzie Foy), who’s convinced that an apparition is living in their home. The apparition is actually their father, Joseph (Matthew McConaughey), traveling from the future to the present to communicate with them about an equation that could save humankind, but poor Tom — best suited to being a farmer, not a scientist — blows it all off. Chalamet’s not in Interstellar very long before he’s replaced by Casey Affleck playing an older version of the character, but Chalamet establishes Tom’s long-suffering, chip-on-his-shoulder energy in a great way that Affleck then builds off as he turns Tom into a tragic villain. Another youthful actor might have been tempted to overdo Tom’s creeping knowledge of his own inadequacy. Instead, Chalamet underplays it, which is just right.

Wes Anderson knew exactly how to use Chalamet, didn’t he? Backcomb that hair, slap a thin mustache on his face, and put Chalamet in front of a chessboard, and you’ve got a particularly poignant representative of a disaffected French adolescent. (Like a serious version of Michael Cera’s François Dillinger alter ego from Youth in Revolt.) Zeffirelli B. is only a sliver of a role in The French Dispatch, but it proves Chalamet’s growing certainty of his own magnetism, and his awareness of how to use his face — in particular his gaze — to convey a contemptuous frustration with the status quo. In the “Revision to a Manifesto” section of Anderson’s anthology film, Chalamet plays the representative of a student-protest movement that’s grown from initial complaints about the women’s dormitory at their university to a larger, more spirited uprising against military conscription and forced service. To communicate and negotiate terms, the two sides nominate Zeffirelli and the town mayor to play a chess game, on which journalist Lucina Krementz (Frances McDormand) reports while also unexpectedly tumbling into a relationship with Zeffirelli. Zeffirelli is purposefully a figurehead here, but Chalamet’s furrowed brow, frown, and languid physicality help him rise to every descriptor Anderson assigns him: “exhilarated, naïve, brave in the extreme.” He’s not a character who could sustain for longer than 20 or so minutes. Within that chunk of time, however, Chalamet helps him feel breathtakingly young and heartbreakingly alive.

Photo: Niko Tavernise/Netflix/Everett Collection

Chalamet is playing the most internet-poisoned person you’ve ever met in Don’t Look Up, and yet he’s somehow this cursed movie’s most tolerable character. Every moment Chalamet is onscreen, he’s delivering a new voice, unexpected intonation, or bizarre physical flourish, but at least he’s matching the surreal tone this overserious movie needs to be anything but a slog. Yes, the placement is high on this list, but again: He’s the best thing about the movie! Chalamet makes dialogue as ludicrous as “I fucking love fingerling potatoes” feel like high art in the midst of this patronizing muck! Such talent must be rewarded.

Chalamet wanted an Oscar nomination bad with Beautiful Boy, and he probably should’ve gotten it. (The BAFTAs and SAG-AFTRA took notice, at least.) In this biographical drama, Chalamet plays Nic Sheff, a promising young artist who starts experimenting with drugs in his teens, goes to rehab before college, and then tumbles into addiction that upends his relatives’ lives and nearly kills him. The film is told primarily through his father David’s (Steve Carell) perspective as the journalist tries to understand exactly what heroin and crystal meth are doing to his son, and as he realizes that he might need to cut Nic off in order to save him. Director Felix van Groeningen and co-writer Luke Davies jump around in time and mostly reject a linear narrative, which doesn’t quite do the material justice; Beautiful Boy sometimes feels like it’s trying to make the predictability of its narrative more interesting with a “Can you guess when this particular scene was?” approach. But Chalamet is undeniable, playing Nic’s worst decisions with an easy confidence that belies exactly how much Nic was destroying his own life. A scene where we see Nic in his college library and then realize he’s using the computer to research the safest way to inject heroin hits so hard because of how calmly and methodically Chalamet looked while putting in his parents’ worst nightmare of a search prompt. This is Chalamet at some of his mercurial best, whether his voice is guttural and otherworldly as he rejects his father’s suggestion of rehab with a screaming “I’m 18, you can’t force me,” or as he coats his face with tears and snot when telling David that he knows he’s a disappointment. Because Beautiful Boy aligns so much with David, there isn’t a lot of backstory for Nic, yet it doesn’t really matter. Chalamet gives the character’s self-destruction and anguish an amount of urgency that explains more about the character than a tidy explanation for his addiction ever could.

Photo: A24/Everett Collection

Chalamet does a Jess Mariano thing in many of his roles, treating everyone around him like they’re not quite as smart as he is and not worthy of his smart-alecky retorts or references, and that’s fine — every generation’s alt-grrls deserve their own bad boyfriends. Lady Bird is the peak of that Chalamet niche, and the film that catapulted him most fully into widespread popularity. (Theatrically in the U.S., it was released three weeks before Call Me by Your Name.) Let me be clear here: Chalamet’s Kyle is a jerk, someone who lies about his virginity so he can get Saoirse Ronan’s Lady Bird into bed and who then essentially disappears from her life afterward. But damn, doesn’t Chalamet make him likable, and again, the key is how he underplays Kyle’s worst qualities so he doesn’t seem quite so bad. He’s not wrong that the U.S. government is using cell phones to track us! He’s right to read Howard Zinn! He walks that perfect teen-bad-boy line in that he’s simultaneously an incredibly soft rich kid unironically using slang like “Hella tight … very baller … very anarchist” and also a preternaturally, cherubically beautiful young man who knows that his looks and his gentle voice will get him far in life with any girl or woman he wants. In Chalamet’s hands, Kyle is a (welcome) menace.

Luca Guadagnino’s cannibal romance Bones and All has long stretches of curiously cold filmmaking, almost like the movie is trying to keep itself as sterile as possible to make its characters’ bloody hunger that much odder. Also bizarre is how much of the movie feels like it was left on the cutting-room floor; more of Michael Stuhlbarg in those ugly overalls would have been nice. But maybe Bones and All is just taking its cues from Chalamet, who delivers a mercurial performance as the drifter Lee. More knowledgeable about his hunger than his love interest, Maren (Taylor Russell), and already living by a code about who to eat and why, Lee has more information about the desires he and Maren feel but also, as a result, is more hardened by it. He kills, he lies, he survives, and Chalamet imbues him with a coiled-up energy that communicates both his willingness to do anything to see another day and his increasing loneliness as a result of that recklessness. He looks so young when dancing to Kiss’s “Lick It Up,” still blood-smeared and buzzing from his last kill, but Chalamet also conveys how that energy can’t last. Just like the next movie on this list, it’s a balancing act that it feels like only Chalamet could do.

Photo: Warner Bros./Everett Collection

Within Chalamet’s filmography, Wonka is an aberration. He’s actually playing happy in this one! And he’s having a pretty good time! Paul King stepped away from the Paddington franchise for this latest stab at Roald Dahl’s iconic story of a wacky chocolatier, and the film is entirely dependent on how successfully Chalamet ingratiates himself to the movie’s singing, dancing, upbeat demands. But if there were ever a reminder of how Chalamet was once a very gung-ho theater kid, this is it. He throws his thin-but-exuberant voice into the original music, he twirls and tap-dances his way through the songs, and he makes a character who in previous iterations has been mostly larger than life believably human. Chalamet (with a particularly luscious head of hair) makes his Wonka a kind-hearted scoundrel and an always-smiling goof, pulling outsize expressions as the script requires and solidifying Wonka as a sympathetic figure. The movie isn’t perfect, its aesthetic a little too glossily Harry Potter–lite and the Keegan-Michael Key character obviously fatphobic. But Chalamet’s shrieking line delivery of “What? You’ve never had chocolate?” is such an all-timer, you might even forgive how the movie has Wonka say “I’m gonna need a factory,” like he’s gathering some kind of suicide squad. Gene Wilder’s Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is a classic, Johnny Depp’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a travesty, and Wonka falls far closer to the former than the latter thanks to Chalamet.

Robert Pattinson has the showier part in David Michôd’s beautifully melancholic adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; and Henry V. (The King is early proof of Pattinson’s propensity for weird little voices. When he smilingly calls English “simple … and ugly,” he’s not wrong.) But Pattinson couldn’t get his freak on without a steady scene partner who can hold down the film’s examination of masculinity, nobility, and national loyalty, and that’s Chalamet as young Prince Hal as he grows into King Henry. Watching Chalamet in The King is like watching a trial run for his work in Dune because the beats are so similar — a young man resisting his destiny, struggling with the expectations of his family and realizing that circumstances outside of his control are pulling him forward into conflict, and eventually seizing the opportunities afforded to him to defend what and whom he loves. (In fact, the roles overlapped; Chalamet was filming The King in summer 2018, when he entered into final negotiations to play Paul Atreides.) And also like in Dune, Chalamet communicates his young heir’s internal turmoil mostly silently, through brooding glares, unyielding posture, and a quiet vulnerability that he combats with exceptional fighting skill. Watch Chalamet in that scene with Pattinson to see how determinedly and composedly he parries Pattinson’s braggadocio, and then watch his pump-up-the-dudes speech to see how he puts his own spin on the iconic “All men are born to die” speech. The range, it’s there.

The amount that Chalamet grew as an actor in the two years between Lady Bird and Little Women is absurd. As Laurie, Chalamet dives into all the emotions that he kept in check in Lady Bird and pulls them up to the surface to create this impetuous, beautiful boy who wears his heart on his sleeve and doesn’t understand why everyone else doesn’t live like that, as well. Laurie is a cautionary tale, of course, a young man with resources and freedoms that the March sisters don’t have who has to learn, through rejection, that the entire world can’t belong to him just because he wants it to. But Chalamet combats the character’s innate privilege by amping up his yearning — so much yearning — and by centering his sensitivity above all other qualities. The scene where Laurie begs Saoirse Ronan’s Jo to marry him is almost impossible to watch for its rawness and innocence; if you asked one of Timmy’s fans when they fell in love with him, this is it.

Presented without comment as evidence of what this man can do to yank your heart out: Chalamet’s Elio crying over the film’s closing credits once he learns that his secret older lover, Oliver (Armie Hammer), is getting married. You don’t need more than this, do you?

As written by Frank Herbert, Paul Atreides is an impossible character, a bundle of contradictions whose specialness is because of all that internal opposition. He’s tentative to embrace either of the divergent destinies his mother and father have laid out for him but curious about what the responsibilities of House Atreides are to the planet of Arrakis, and drawn to Chani even as he doesn’t entirely understand the Fremen culture, and conflicted about his own biological relationship to the evil House Harkonnen while also knowing that having some of their blood gives him an additional layer of nobility. It’s difficult to transplant that character from the page to the screen, and I’d argue that neither David Lynch nor Villeneuve fully hacked it. It’s undeniable, though, that Chalamet captures the churning spirit of Paul’s inner life in the first Dune and conveys, with those huge doe eyes, the set of his jaw, and the haughtiness of his tone, all the ways in which Paul’s being pulled apart by the expectations upon him. The first Dune is a story of transformation — the Bene Gesserit’s genetic engineering catches up with Paul as he starts to tap into his abilities, House Harkonnen destroys most of House Atreides and leaves Paul with a mantle to carry in defending it — and Chalamet establishes the baseline of Paul’s youth and then slowly matures aspect after aspect of it. The details are what matter here, from the grit of his grinding teeth during the Gom Jabbar test to the wonder in his eyes when he sees Zendaya’s Chani for the first time and realizes she exists outside of his dreams. Paul requires an actor who can be both naïve about what’s awaiting him in life and resolute once he finally faces it, and Chalamet engineers both. Plus, he looks pretty cool during those knife fights.

Photo: Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures

Although most of Chalamet’s greatest work is highly demonstrative, plaintive and tear-soaked, he’s also capable of an undercurrent of aloofness. That detachment made his performances in The French Dispatch and Lady Bird quite good; it makes his Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown great. Biopics are a tricky thing: Is the actor expected to mimic the person, or should they evoke the person? Going with the latter route allows for a certain amount of analytical awareness to enter into a performance, since the actor isn’t beholden to identical copycat behavior, and that’s what gives Chalamet’s performance in A Complete Unknown such sneaky power. The movie itself is prodding at the idea of who Dylan even was, how he mythologized himself by changing his name, avoiding explaining the motivations for his songs, and purposefully burning bridges with the very same musical allies who helped buoy him to early success; frankly, A Complete Unknown basically suggests that Dylan was an asshole. And, well, one look at this list and you know that Chalamet is particularly talented at playing assholes. Chalamet performing as Dylan is fine, but what really lingers is the way that Chalamet nails Dylan’s body language at the time, that mixture of a cocky stride and a hidden-behind-sunglasses retreat — the way he was running toward his goals while hiding from others, and ultimately, himself.

This stunt queen. For the past few months, Chalamet has been around the world promoting Marty Supreme, and all of it — the windbreakers, the dancing, the podcast and TV appearances — would be annoying if, well, his turn as Marty Mauser wasn’t so obviously the best work of his career so far. Remember when Chalamet said he wanted to be one of the best? Well, art imitates life, life imitates art, yadda yadda yadda, Timmy is Marty and Marty is Timmy. Many comparisons have been made between Chalamet and Leonardo DiCaprio, and although I don’t quite see it, Marty Supreme is absolutely Chalamet’s Catch Me If You Can, a showcase for how charming, manipulative, and single-focused Chalamet can make a character. As Marty Mauser, Chalamet is a selfish dreamer, so convinced of the idea that he’s the world’s best Ping-Pong player that he’ll do anything, and use anyone, to get ahead, and the only reason you don’t hate this guy while watching Marty Supreme is because Chalamet layers all of his egocentrism with an earnest belief in himself. Chalamet could probably do Marty’s motormouth monologuing in his sleep, but the physical demands of the role are immense, too, and he contorts and twists his body into that of a furiously competitive athlete as prone to knockout parries as he is to temper tantrums. This is the kind of role that will be so definitive for Chalamet that eventually, maybe, he’ll need to do something totally different to realign our perceptions of who he is and what he’s capable of. For now, though, Marty Supreme proves that the latter is a damn lot.