Tiny crystals buried in Australia’s coastal sands have captured signals from space, helping scientists chart erosion and geological shifts across millions of years. Using a rare gas formed by cosmic rays, researchers have managed to reconstruct hidden timelines written not in fossils or rock layers, but in grains no thicker than a strand of hair.

Developed by scientists at Curtin University, in collaboration with teams from the University of Göttingen and the University of Cologne, this technique focuses on zircon, a hardy mineral that has endured countless cycles of erosion and transport. Encased within each grain lies a microscopic archive of its exposure to the open sky, a new way of reading the Earth’s surface history.

Why does this matter? Because it gives geologists a tool they’ve never had before: a natural clock.

Tracing Deep Time With Space-born Particles

The key to this method lies in krypton, a noble gas created when cosmic rays, high-energy particles from space, strike minerals like zircon at Earth’s surface. This process, called cosmogenic nuclide production, slowly fills the crystals with measurable amounts of krypton over time. That trapped gas, once extracted and analyzed, tells scientists just how long the mineral hung around on or near the surface before getting buried.

It’s almost like geology with a stopwatch. According to a research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, lead author Dr. Maximilian Dröllner explained that the method unlocks access to ancient landscapes far older than what traditional tools allow.

“Our planet’s history shows climate and tectonic forces can control how landscapes behave over very long timescales,” he said. And now, scientists can finally measure that behavior with surprising precision.

Each zircon is less than 0.1 millimeters across, but don’t let the size fool you, they’re among the toughest minerals out there.

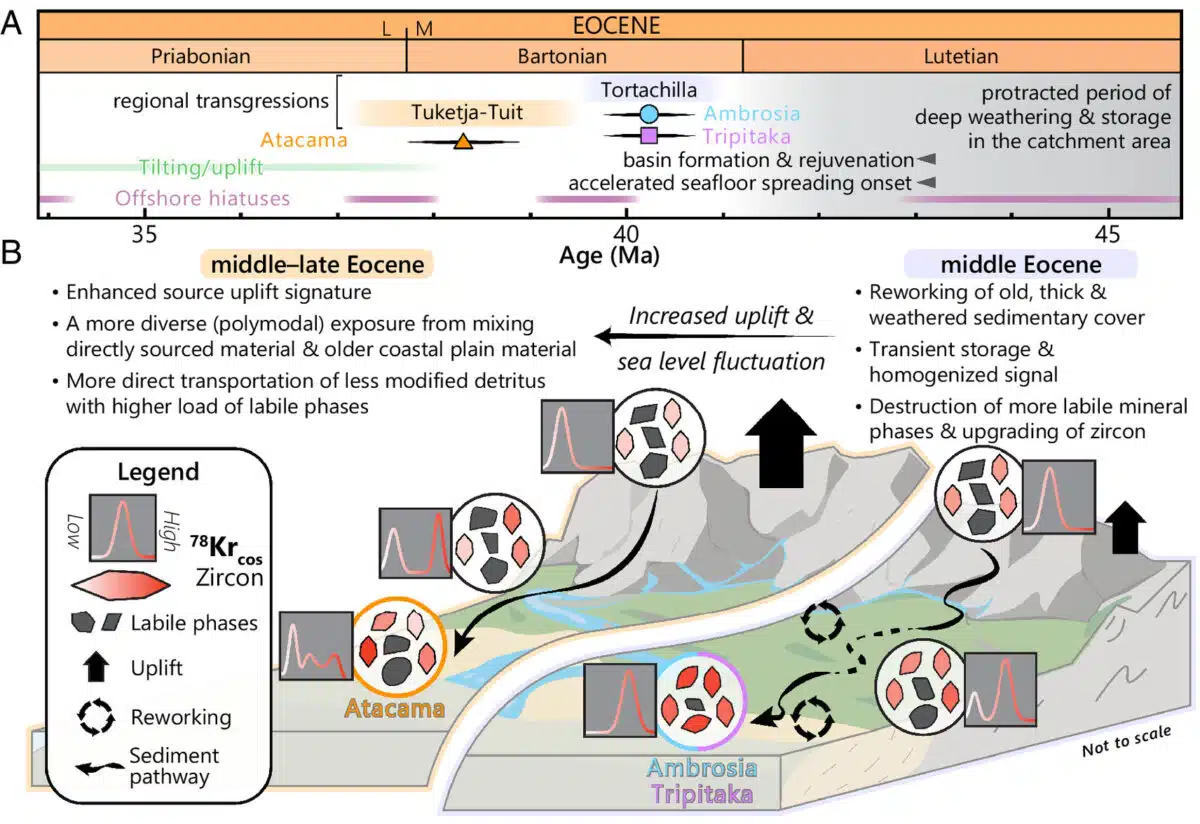

Overview of sedimentary and tectonic processes in Australia during the Eocene (45–35 Ma). Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Overview of sedimentary and tectonic processes in Australia during the Eocene (45–35 Ma). Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

When Nothing Moves, Everything Stays

One of the more surprising findings? In places where tectonic movement is minimal and sea levels are consistently high, sediments barely budge. These calm conditions mean minerals can hang around near the surface for millions of years without being flushed away or buried deep underground.

Professor Chris Kirkland, co-author and lead of Curtin’s Timescales of Mineral Systems Group, pointed out that such scenarios change how we think about landscape evolution. According to him:

“As we modify natural systems, we can expect changes in how sediment is stored in river basins and along coastlines.” That’s not just a note for geologists, but for planners, engineers, and environmental scientists looking at long-term coastal behavior.

This sort of pause in erosion and sediment movement is usually invisible using older techniques. With cosmogenic krypton, though, researchers can finally detect these quiet geological periods and understand how they affect broader landscape stability.

Electron microscope view of zircon grains, each storing cosmogenic krypton from surface exposure. Credit: Maximilian Dröllner

Electron microscope view of zircon grains, each storing cosmogenic krypton from surface exposure. Credit: Maximilian Dröllner

Where The Minerals Wait

The research also has practical implications, particularly for mineral exploration. Australia is home to vast mineral sand deposits, and understanding how these formed over geological timescales could help identify future resources more efficiently.

SciTechDaily reports that Associate Professor Milo Barham explained the connection between climate patterns and resource concentration:

“Extended periods of sediment storage allow durable minerals to gradually concentrate while less stable materials break down.”

In other words, the longer zircon stays near the surface, the richer the sediment layer becomes in valuable materials.