Until roughly eight years ago, Intellivision was in competition for last-place in the retro-gaming nostalgia sector. Its 1980 launch led to a few years of significant sales for its handlers at global toy giant Mattel, but the brand never overcame the 1983 home-console crash. “Intellivision” didn’t persist with compelling hardware, unique software or shifting to markets like arcades or PCs, leaving its ranking low on both retro stores’ shelves and collectors’ hearts.

In 2018, the brand enjoyed a bit of buzz after being acquired by a group that announced the Intellivision Amico, a home console modelled after the original system’s aesthetics but with gamepad tweaks like dedicated touchscreens and motion sensors. That buzz turned dire, however, thanks to factors like underwhelming Amico specs, countless crowdfunding attempts and interminable delays.

Strangely, that years-long weirdness may have worked out in favour of Intellivision’s legacy as a gaming platform. In May 2024, Amico Entertainment, LLC sold the original console’s branding and over 200 games’ rights to Atari of all companies – arguably to settle publicly reported, Amico-related financial matters. At this time, a resurgent Atari had launched retro hardware like the Atari 2600+ mini console. Intellivision, Atari’s one-time rival, might follow suit.

Roughly 18 months after that deal, we indeed have a piece of hardware in our hands – the $149 Intellivision Sprint – that looks like an Intellivision and plays the console’s games. Sprint combines the original console’s games, controls and quirks with the niceties of HDTV compatibility, wireless controllers and expandability.

While we do not necessarily recommend Intellivision Sprint, its current sold-out allocation suggests that a target audience indeed exists – and for such a buyer, Sprint is equal parts solid and underwhelming. Additionally, we’re hard-pressed to think of a better all-in-one way to accurately and conveniently access the original system’s catalogue, and Sprint’s launch is a good excuse to review exactly what made the original Intellivision stand out, at least for a brief 1980s moment.

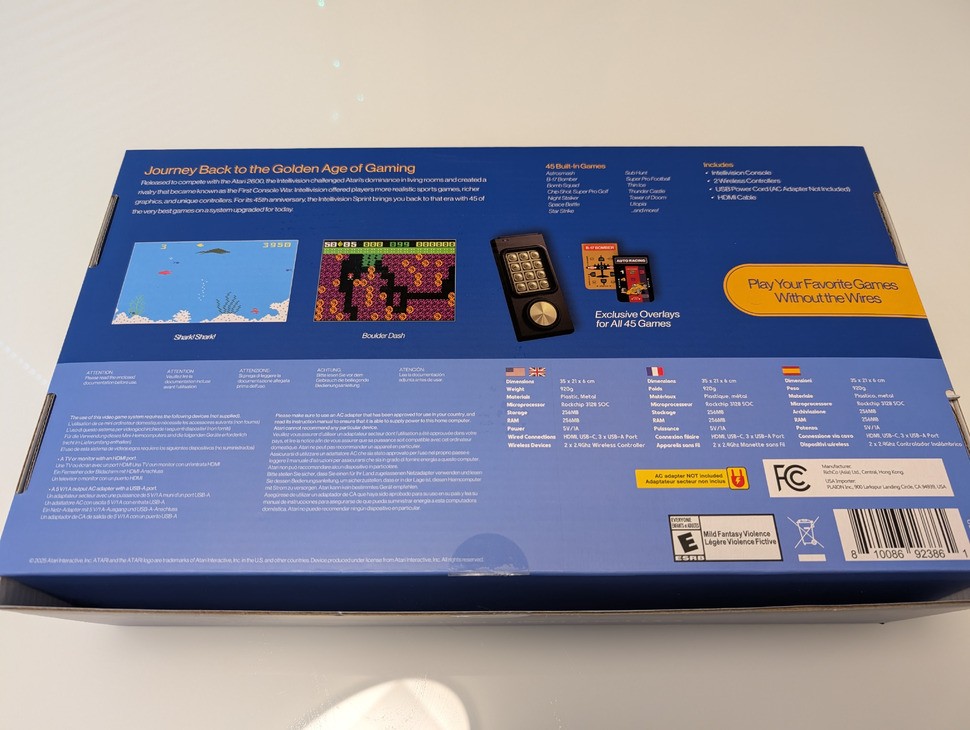

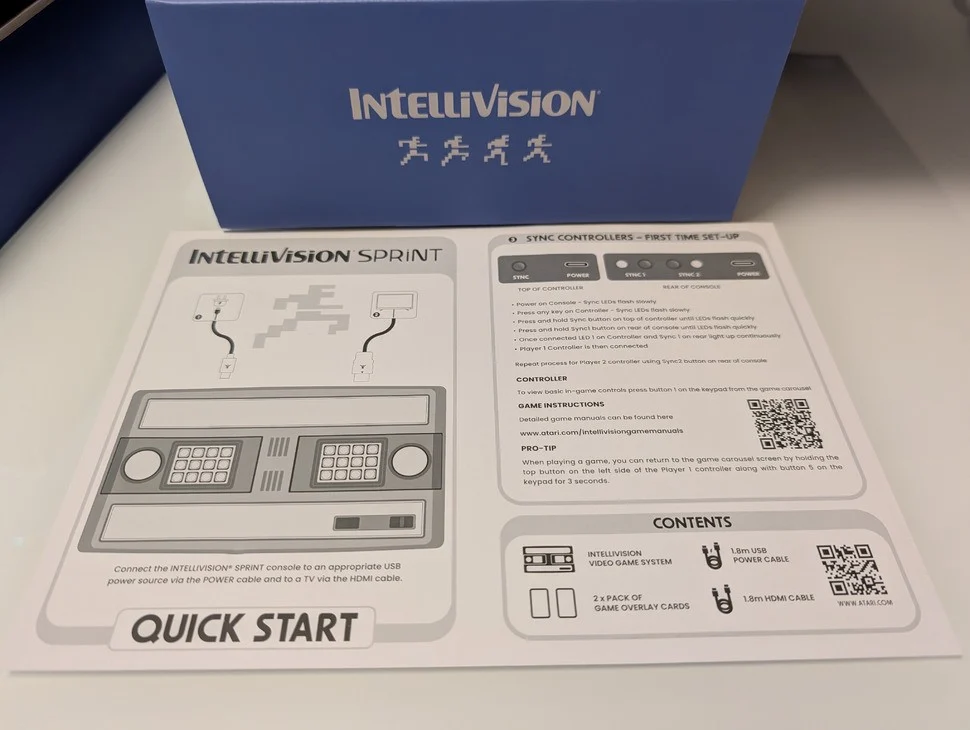

Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Sprint unboxing, including a peek at its single printed-out sheet. The system includes HDMI and USB Type-C cables, but not an AC adaptor. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Intellivision’s introduction as a TV video game system in the 1980s was preceded by an important development at Mattel: explosive handheld gaming sales. Mattel’s fortunes as a toy manufacturer had soured by the mid-1970s for a number of historically fascinating reasons (slumping toy sales, corporate shenanigans). Around the same time, home electronic games from other toy makers had grown in popularity.

As one idea to spur revenue, Mattel Toys looked at product lines like Pong clones and considered their own ideas, leaning at first towards toy-like designs. Management asked engineers to model a game with the same size and LED-screen functionality as a handheld calculator, hitting the sweet spot of small cost and size that Mattel could easily sell at toy stores. Mattel’s work on this concept actually took place years before Nintendo’s own R&D on its hugely popular Game & Watch line of handheld games – each using calculator-like panels and technology in different ways.

The 1977 commercial launch of Mattel’s first two handheld LED-display games, Auto Race and Football, employed small, red lights to simulate cars and American football players, respectively, with simple button controls to move them through challenging conditions. Their reasonable prices and handheld form factors proved a smash hit, selling “500,000 a week” by mid-February 1978.

An original Mattel Electronics commercial for its handheld “Football” game.

Mattel and its competitors produced more electronic handheld games as a result, ranging from elaborate video game facsimiles to toy-like concepts like horoscope readers and “Simon”-style memory-sequence fare. By then, Mattel had already spent years exploring the possibilities of low-cost computer chips as drivers of their own TV-connected devices, and after delays and internal adjustments, they didn’t decide on either a cartridge-ROM game console or a home computer. They originally marketed Intellivision (“intelligent television”) as a hybrid.

Mattel softened the blow of Intellivision’s originally high price point with promises of an eventual, optional keyboard attachment, complete with a built-in cassette-tape drive and other attachments, that would make it operate more like a PC. The idea being, a console that was both more powerful and more expensive than the 2600 would be easier to stomach if its final computer-calibre bundle still cost less than rising home computers like the Apple II. But after its own delays, the Intellivision keyboard kit eventually launched in incredibly limited numbers before being announced as “cancelled” – and the stink of “false advertising” drew in an FTC investigation in the United States.

After a test-market trial in 1979, Intellivision formally launched in 1980 at the high-for-its-time price of $250. That cost came largely due to a General Instruments chipset that handily surpassed the older Atari 2600’s capabilities. Its 10-bit bus, 2MHz processor and heaps of RAM led to substantial jumps over the 2600 in categories like on-screen sprites, on-screen colours and legitimate background tile support.

To aid game makers, an “EXEC” system pre-loaded on the console essentially served as the game industry’s first API, in terms of having common programming routines and assets available – including the console’s iconic “running man” sprite. This was particularly useful for early cartridges with reduced ROM sizes, but the EXEC system’s overhead came at a price of a choppy 20Hz maximum refresh rate.

George Plimpton promotes Intellivision in a television ad from 1980.

Toy companies didn’t traditionally engage in head-to-head advertising campaigns at the time, but Mattel’s Football handheld had faced such a campaign from handheld-game rival Coleco, so Mattel followed suit with its own Intellivision-versus-Atari TV campaign. The results, starring popular critic and gaming fan George Plimpton, turned the public tide of reputation and sales towards Intellivision – but only briefly.

Though Intellivision hardware and software persisted until the late 1980s, Mattel didn’t steward the system for long. Despite a strong Intellivision launch year, Mattel Electronics was shuttered by early 1984 in the wake of tanking Intellivision sales and other corporate factors. The console and its library of software were acquired by a consortium that included ex-Mattel staffers, but they were unable to deliver the kinds of software or hardware advancements that would win over the masses.

Still, Intellivision lived on in the form of numerous software library collections for consoles and PCs over the years, albeit never with the unique combination of numerical-pad controllers and per-game, printed-out overlays that clarified what each button did in intensive games. The new $149 Intellivision Sprint console is interesting for a few reasons but most immediately so because it brings those two elements back in a big way – at least, for the first time since 2014’s lesser Intellivision Flashback plug-and-play system.

The Intellivision Sprint gamepad is the same size and design as the original 1980 version – with the exception of a “sync” button and a USB Type-C port for charging. — Image: Sam Machkovech

The Intellivision Sprint gamepad is the same size and design as the original 1980 version – with the exception of a “sync” button and a USB Type-C port for charging. — Image: Sam Machkovech

The base Sprint package includes one of the larger chassis we’ve seen on a recent, HDMI-out emulation box, as it preserves the original Intellivision “master component”‘s use as a gamepad docking station. Only, this many decades later, instead of coiled cords, this pair of gamepads connects wirelessly to the Sprint via a built-in 2.4GHz receiver.

Intellivision’s unique controller, quite frankly, isn’t great on an ergonomic basis. In trying to stand out from Atari’s one-button, big-joystick standard, Mattel opted for remote control-like familiarity, but the simultaneous requirement of directing characters with its “control disc” and clicking buttons all over the controller is arduous.

The original disc included support for 16 discrete directions – a level of fine detail that game consoles didn’t again approach as a standard until analogue joysticks became common. My initial Intellivision Sprint tests didn’t feel great on this front, however, with directional taps always feeling miscalibrated by 10-15 degrees. In researching the system on AtariAge’s forums, I saw a recommendation to loosen the Sprint gamepads’ screws by a quarter rotation. After using my screwdriver, the disc feels smoother and more responsive , especially in tank-combat games like Armor Battle – though its cardinal-direction prowess still leaves something to be desired in games like Atari’s Intellivision port of Pac-Man.

When gamepads are inserted into the Sprint, they connect to Type-C plugs and fit neatly into the chassis. — Image: Sam Machkovech

When gamepads are inserted into the Sprint, they connect to Type-C plugs and fit neatly into the chassis. — Image: Sam Machkovech

The original 1980 gamepads included a telephone-like number pad, paired with a small crevice to insert a per-game control guide. Depending on the game, the extra buttons might enable selecting a strategy in sports – a massive genre for the America-focused console – or a unit type in a war sim. Interestingly, Intellivision used these buttons as a four-way directional gun in Night Stalker mere months after Eugene Jarvis’s Robotron 2084 reached arcades – meaning, Mattel and Williams effectively launched this control innovation simultaneously.

But many of Intellivision’s launch games left the number pad underused, with per-game inserts merely featuring artwork and a choice between one player or two. Worth noting: Intellivision’s 1980 launch games may have looked better than those on the rival Atari 2600 console, but some were hamstrung with tiny ROM allocations on carts, which meant they didn’t support enemy AI. In early games like Sea Battle, two-player modes were the only option.

On Intellivision Sprint, this number pad lives on, and it’s nothing to shout about. Mushy, hard-to-press buttons resemble those on original hardware instead of the better stuff found on modern TV remote controls, let alone traditional controllers. But they get the job done. Four action buttons line the controller’s edges, and they’re clickier and more responsive than in original Intellivision controllers but could have used a modern revision in terms of size and placement.

Sprint comes with 45 gamepad inserts for each of its controllers – so, 90 total. They’re a bit fiddly to insert and remove. Then again, this was the case for the original Intellivision, as well. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Sprint comes with 45 gamepad inserts for each of its controllers – so, 90 total. They’re a bit fiddly to insert and remove. Then again, this was the case for the original Intellivision, as well. — Image: Sam Machkovech

Intellivision Sprint includes a pack of physical gamepad inserts for all 45 of its built-in games – two inserts per game, in fact. This is ostensibly to support two-player living room play, though even single-player fare like Tower of Doom gets a second insert – so, slap its cool, bonus skull art on your school notebook if you want.

The inserts are as close as this system comes to providing an “instruction manual” for its built-in games. There is something charming about picking through the high-quality inserts, inserting a new one into your gamepads and trying a game you’ve never played before. That’s nicer than merely making a digital selection in a menu – though it would have been great if Sprint came with an RFID reader that identified an insert and booted its respective game, a la homebrew card readers available for platforms like MiSTer FPGA.

But some of these games are grotesquely obtuse – common in an era where tiny graphics and entirely new game mechanics were the norm – and the inserts only help so much. Atari has supplied a QR code for each game in Sprint’s menus that is intended to link to useful instructions, but these point to instruction manual scans hosted by the Atari-owned community site MobyGames. This site’s tiny manual-scan interface is not mobile-friendly – you’re scanning a QR code with a phone, after all – and some of Atari’s QR code links as of press time point to empty pages.

Should you wish to switch either gamepad from Player One to Player Two or vice versa, there’s a long-press sync button process, but while this may seem like the stuff of a Bluetooth device, there’s no BT – and thus no compatibility with your favorite BT gamepad. Atari advertises support for USB Type-A gamepads as plugged into the back of the system, but none of my Sony, Xbox or 8Bitdo pads work with Sprint’s latest firmware.

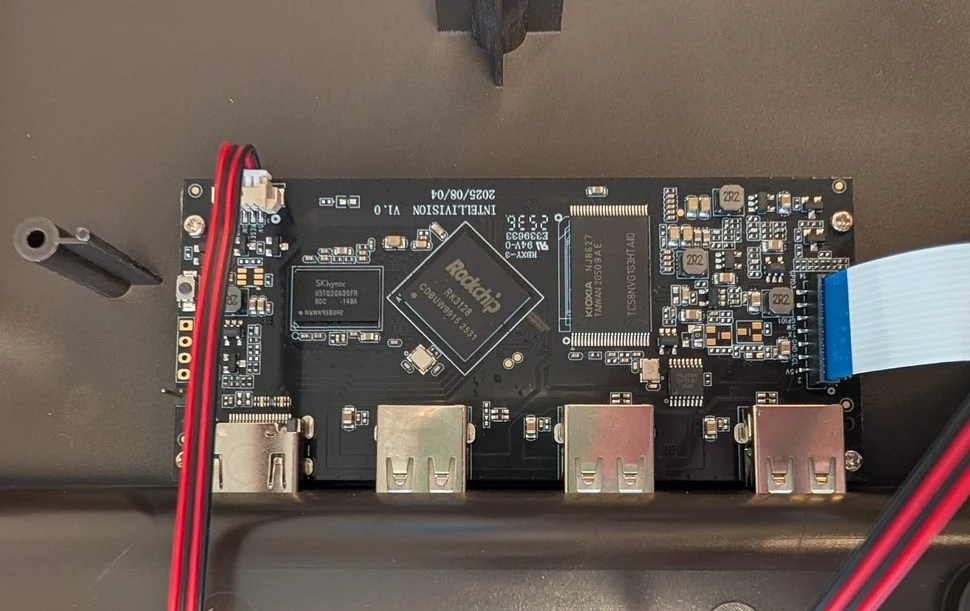

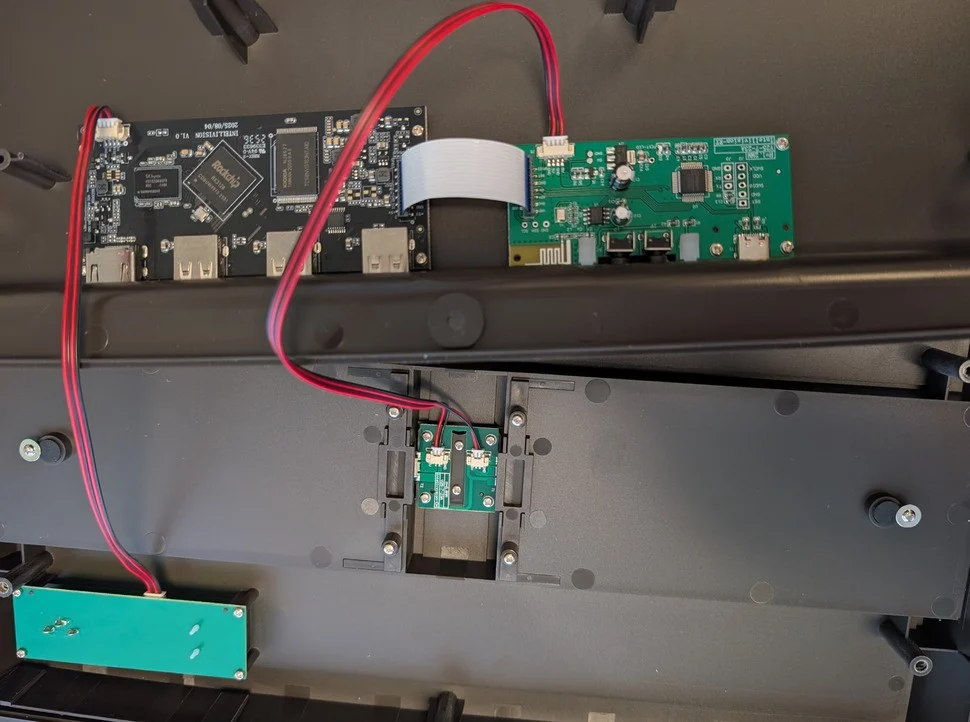

We opened the Intellivision Sprint so you don’t have to. This is a peek at its mainboard. — Image: Sam Machkovech

We opened the Intellivision Sprint so you don’t have to. This is a peek at its mainboard. — Image: Sam Machkovech We opened the Intellivision Sprint so you don’t have to. This is a peek at its mainboard. — Image: Sam Machkovech

We opened the Intellivision Sprint so you don’t have to. This is a peek at its mainboard. — Image: Sam Machkovech

I understand why someone would prefer to use a standard gamepad to more comfortably play Intellivision fare on this system, and I hope support on that front improves. At AtariAge, someone from the Plaion hardware team responsible for Sprint has avidly responded to customer queries, which suggests the device will receive continued support in the short term.

I’m hopeful Plaion answers an additional, lingering question: whether Sprint’s wireless gamepads may ever work with other devices in either wired or wireless mode, particularly Windows PCs and MiSTer FPGA emulation boxes. This is due in part to Sprint’s inherent limitations as an Intellivision playback machine.

Its Rockchip RK3128 chipset technically surpasses the specs found in other recent plug-and-play systems, complete with 1080p resolution support, yet on Sprint, it maxes out at 720p resolution. This isn’t by itself a deal-breaker for Intellivision’s 160×96 default resolution, but the OS’s lack of integer-based scaling as an option leaves the image unnecessarily blurry. Sprint also forgoes any scanline or CRT-like filters, which aren’t necessarily great in most 720p systems but would have been an upgrade over the existing uneven upscale to 720p, which leads to issues like horizontal movement shimmer.

The other real pain point for Sprint is its lack of a cartridge slot. Atari’s other recent 2600+ and 5200+ plug-and-play systems have included cartridge support, and it’s unclear whether Sprint skipped this feature as a cost-cutting effort. Where Intellivision Sprint shines, on the other hand, is its unabashed support for software expansion… if you’re willing to go through hoops.

These Activision-published games, as seen in the Intellivision Shift interface, must be manually added to the new system by way of a plugged-in, properly-formatted USB flash drive.

These Activision-published games, as seen in the Intellivision Shift interface, must be manually added to the new system by way of a plugged-in, properly-formatted USB flash drive.

Atari does not formally advertise this Sprint feature on its site, but word spread quickly about the system’s ability to ignore its built-in game storage in its boot sequence and instead process whatever properly formatted files it finds in an attached USB Type-A flash drive. As a result, the AtariAge forums, along with interested content creators, have become a hodgepodge way to access materials and guides for turning your own Intellivision cartridges and ROMs into a Sprint-ready collection of games.

The steps currently needed to create a Sprint-ready flash drive from scratch – at least, one that includes the kind of useful images, text and configuration files needed to cleanly operate in Sprint’s interface – are absolutely cumbersome. The open-source Sprint Game Manager software is serviceable enough if you know what you’re doing, but it requires that users bring all of their own assets – box art, game images, descriptions and even metadata – and feed them into its database one game, and one data field, at a time.

Community-developed software like Hakchi, which can add games to HDMI-connected emulation boxes from Nintendo and Sega, is far more capable of translating a collection of games to a convenient and accessible data set. I’m hopeful Intellivision Sprint gets something smoother before long. Until then, since AtariAge doesn’t pin its most useful comments to the top of its Sprint-specific forums, you’ll want to search said forums to find a pre-made pack of metadata and image files, then manually add your own collection of ROMs – and manually change every game file name to match your downloaded metadata.

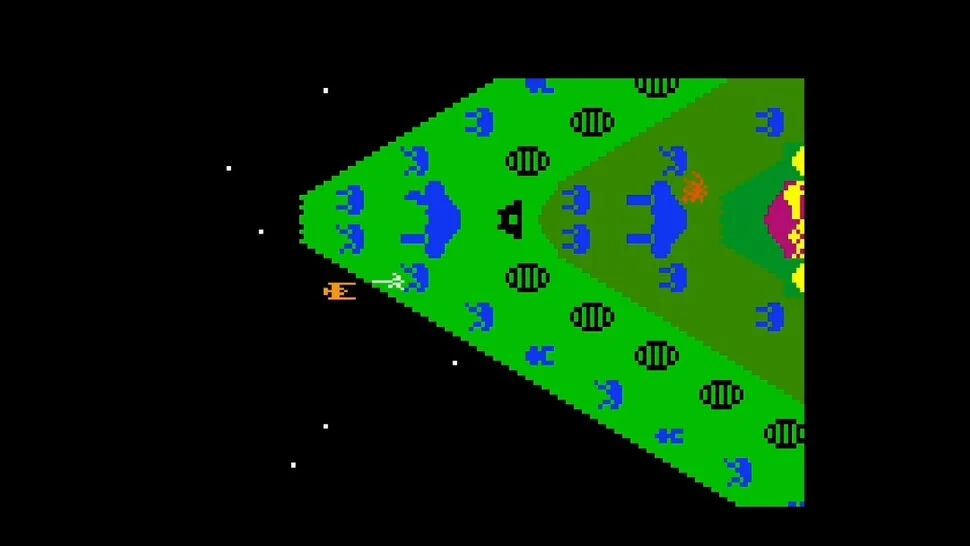

The Dreadnaught Factor from Activision, as played on Intellivision Sprint in 720p resolution.

The Dreadnaught Factor from Activision, as played on Intellivision Sprint in 720p resolution.

My experience making sense of Sprint’s expansion capabilities was fraught in part by seemingly functional USB sticks throwing up errors. After nearly a day of forum perusal and trial-and-error, however, I wound up expanding Sprint’s default 45-game selection with dozens of games that didn’t make the cut. This feature supports embedded folders, which is handy, but even this requires fiddling with file order on a flash drive as opposed to being compatible with the Sprint on-screen interface’s “sort” function.

Intellivision’s software library was thick with licenses, with its earliest sports titles featuring splashy branding from official American sports leagues and its biggest action and adventure games featuring pop-culture phenoms like Pac-Man, Dungeons & Dragons and TRON. These, unsurprisingly, are nowhere to be found in Sprint’s official game lineup. Additionally, while Mattel and INTV Corp. games fill out the pre-installed selection, companies like Coleco, Mattel, Sega and Activision don’t make the cut. I’d love for at least some of the console’s license holders to shake hands and let Sprint owners access these otherwise wholly dead software libraries on the up-and-up. Until then, you’ll have to scour used game stores and rip cartridges yourself, or figure out other means.

No matter which Intellivision games you play, you’ll want some kind of instruction manual handy – and preferably not one of the tiny ones linked via the Sprint’s QR codes. As but one example, with the pack-in game Auto Race, I struggled for a while to figure out that its single-player mode doesn’t boot until you grab the player-two gamepad and hit its “enter” key at the startup screen. That’s to say nothing of the complicated, military bombing-run adventure of B-17 Bomber or the town-building, versus-combat ambition of Utopia.

B-17 Bomber takes advantage of the Intellivision’s number pad to let players switch perspectives in the course of its action, here alternating between a first-person view from a gunning platform and a top-down view of terrain to be bombed.

B-17 Bomber takes advantage of the Intellivision’s number pad to let players switch perspectives in the course of its action, here alternating between a first-person view from a gunning platform and a top-down view of terrain to be bombed. B-17 Bomber takes advantage of the Intellivision’s number pad to let players switch perspectives in the course of its action, here alternating between a first-person view from a gunning platform and a top-down view of terrain to be bombed.

B-17 Bomber takes advantage of the Intellivision’s number pad to let players switch perspectives in the course of its action, here alternating between a first-person view from a gunning platform and a top-down view of terrain to be bombed.

But those three games – included with the default Sprint collection – are each great examples of the Intellivision difference for its time. Auto Race’s top-down racing was spread across an ambitious, connected map with colourful graphics; B-17 Bomber’s voice synthesis alerted players about impending threats and objectives, which players could respond to in real time while alternating between first-person and top-down viewpoints; and Utopia is a proto-RTS with resource management and primitive, real-time battling tactics.

Intellivision also hosted solid top-down maze games like the 1982’s laser-filled Night Stalker and 1986’s elaborately drawn Thunder Castle, each surpassing simpler Pac-Man clones – not to mention the eventual Atari port of Pac-Man to the Intellivision, which handily surpassed the 2600’s technical limitations. And Mattel’s D&D-branded adventuring games – including the reworked Tower of Doom once the license was lost – each had their own mix of ambition and clunkiness to push adventuring games beyond anything seen on the 2600, including a massive maze-crawling adventure in 1982 and a pseudo-3D dungeon-crawling perspective in 1983.

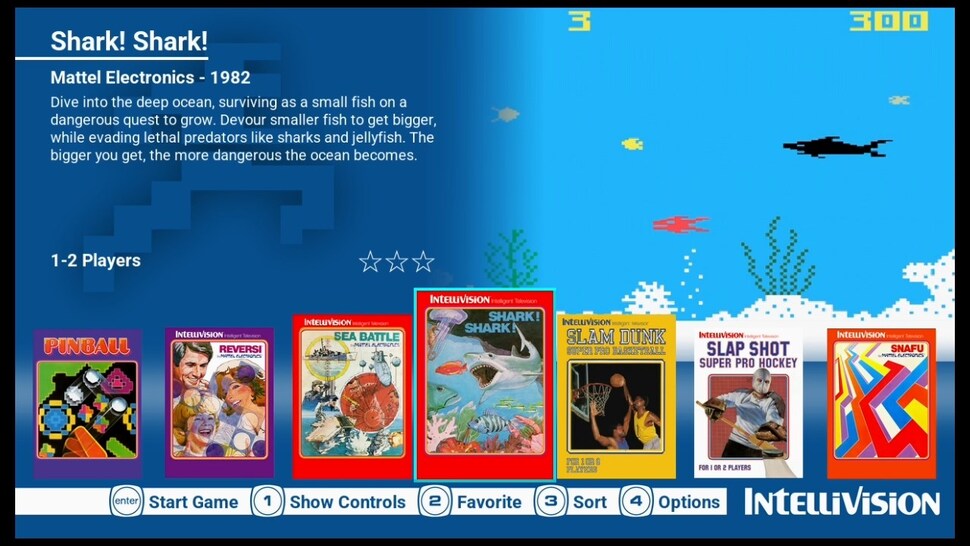

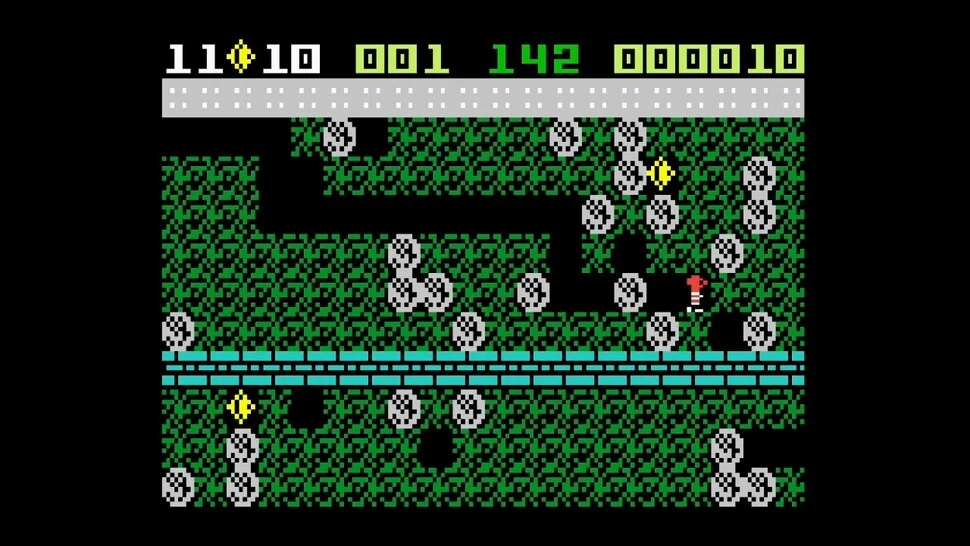

Beyond its era’s technical prowess, Intellivision Sprint plays host to a surprising amount of pick-up-and-play fun – especially with a second player in the same room. Its emphasis on American sports is solid, with basketball, baseball and American football all receiving a number of simple, solid translations that don’t require a manual to understand and benefit from detailed sprites and colourful playfields. Its port of 1985’s Boulder Dash, a Mr. Driller predecessor released on other 1980s platforms, pushes the system’s RAM with screen-filling chaos. And while Shark! Shark! was weirdly romanticised in the Amico hype cycle, here on Intellivision Sprint, its “eat smaller fishes, grow bigger, repeat” gameplay loop is modest, cute and surprisingly addictive.

Screens of the default Sprint interface, the spelunking action of Boulder Dash and the top-down racing of Auto Race.

Screens of the default Sprint interface, the spelunking action of Boulder Dash and the top-down racing of Auto Race. Screens of the default Sprint interface, the spelunking action of Boulder Dash and the top-down racing of Auto Race.

Screens of the default Sprint interface, the spelunking action of Boulder Dash and the top-down racing of Auto Race. Screens of the default Sprint interface, the spelunking action of Boulder Dash and the top-down racing of Auto Race.

Screens of the default Sprint interface, the spelunking action of Boulder Dash and the top-down racing of Auto Race.

$250 in 1980 US currency was a lot for a gaming system, yet with the Atari 2600 in the immediate rearview, it’s easier to recognise the technical prowess and ambitious gameplay that Intellivision delivered for its era at such a price. A different gaming history might have seen Mattel push Intellivision’s limits for a few more years before the NES swept the industry, though other game makers took up that torch, anyway. INTV Corp. emerged from the ashes of Mattel Electronics’ dismantling to continue manufacturing consoles and making new cartridges until 1989, while a burgeoning homebrew community continues developing Intellivision-compatible games to this very day – including paid, downloadable ROMs compatible with the Sprint.

Though it represents an interesting-if-brief era in gaming history, Intellivision Sprint’s current $149 price is its worst barrier to entry. I love being able to buy these two gamepads and a substantial library of original titles, and I appreciate extras like physical gamepad inserts and paths to expand its game selection. Plus, Sprint’s use of the open-source jzIntv emulator is welcome, in terms of classic gameplay accuracy and minimal emulation-based input lag.

But at this price, I expected niceties like 1080p resolution support, additional visual-mode toggles, a printed booklet with instructions for the included games, a path to using these gamepads on other devices I own and – most egregious of all – some kind of original cartridge adapter. A few of those requests may be feasible with downloadable updates down the line, and I hope wired Sprint gamepad support on PCs and other devices is in the cards from the hardware team at Plaion.

Despite my criticisms, Intellivision’s most faithful fans clearly wanted to support Atari’s acquisition and support of the Intellivision brand, as evidenced by Sprint’s current sell-out status at most retailers as of press time. And as far as an HDMI-capable Intellivision emulation box, Sprint ticks just enough of the boxes to be a worthy piece of Mattel’s historical record. Somehow, Intellivision lives.

Special thanks to the Electronic Handheld Games Museum and the podcast They Create Worlds for invaluable information and reporting I drew upon about the history of Mattel Electronics and Intellivision.