In the quest for room-temperature superconductivity, an international team of physicists has uncovered a link between magnetism and the mysterious phase of matter known as the pseudogap, which may finally yield clues to achieving superconductivity above frigid, artificial temperatures.

Given the artificially cold temperatures on which current superconducting technologies rely, making their use impractical for many applications, the search for new room-temperature superconducting materials is a major goal of applied physics research.

Now, physicists from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Germany and the Center for Computational Quantum Physics (CCQ) at the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute in New York City are potentially helping to advance scientists closer than ever to superconducting at practical temperatures, as reported in a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Superconductors

Superconductors are materials that allow electrical current to flow without resistance. However, even in superconducting materials, the property only becomes active below a threshold temperature. This limits technological applications, as the materials require bulky cooling apparatus to maintain the desired temperatures, which are well below typical room temperatures.

Despite the volume of research involving superconductivity, in many ways it remains poorly understood, awaiting insights that will enable the next generation of quantum computing and other applications.

Some superconductors operate at what are considered “high temperatures,” although, in practical terms, these are still well below typical room temperatures and usually only slightly above absolute zero. What is interesting about those materials, however, is that they tend to exhibit a “pseudogap state” in which electrons begin to behave strangely as they transition to a superconducting state.

Understanding how this state leads to superconductivity could be essential to revealing the mechanisms at play and then applying them to produce room-temperature superconductors.

Testing the Pseudogap

Advancing toward resolving this long-standing issue, researchers used a quantum simulator set slightly above absolute zero to monitor electron spins. They identified that the up or down spins of electrons were influenced by their neighbors in a universal pattern.

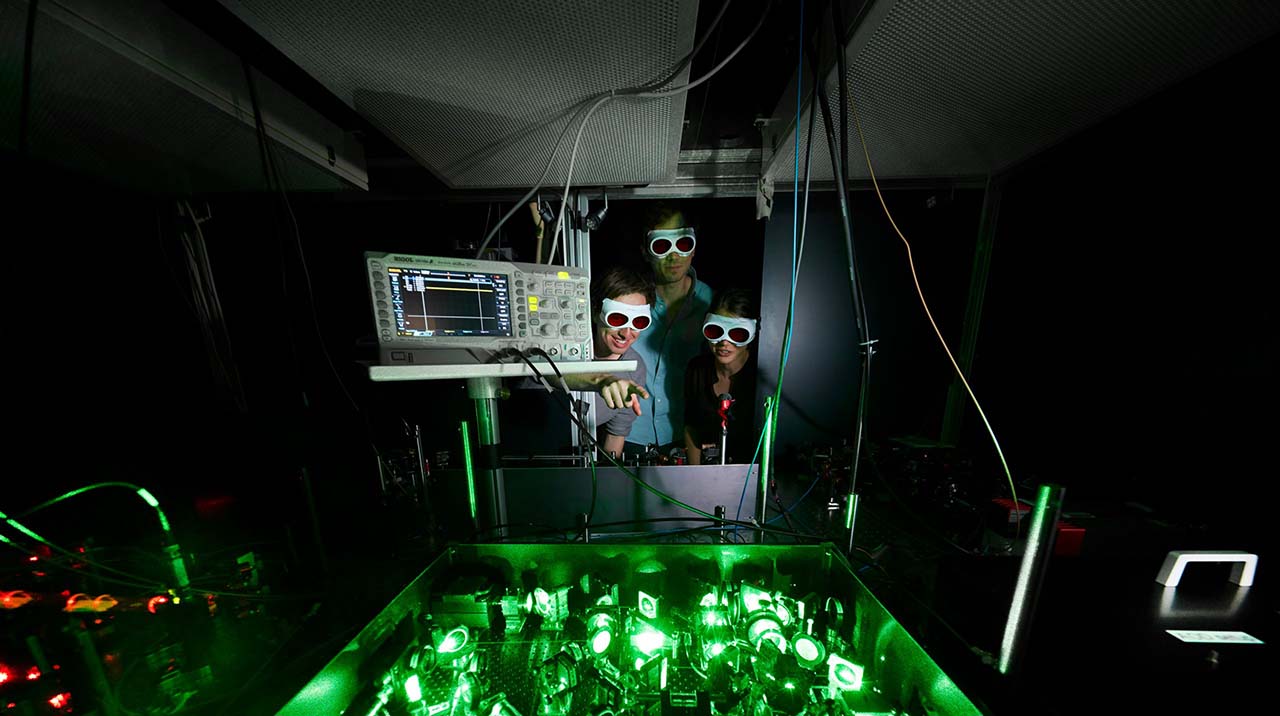

At the center of the team’s work was the Fermi-Hubbard model, which describes electron interactions in a solid. The research team’s simulations successfully recreated this model, rather than a real-world material, using lithium atoms in an optical lattice of laser light at temperatures on the order of billionths of a degree above absolute zero. Simulations allowed the researchers a level of precision control impossible in real-world experiments.

When materials host an unaltered amount of electrons, they spin in an alternating pattern called antiferromagnetism. Through a process called “doping,” electrons can be removed, disrupting the magnetic order in a way that physicists had long assumed was permanent. Yet in the new observations, the team discovered a hidden layer of organization present beneath the seeming chaos at very low temperatures.

Observing Quantum Activity

To collect observations of their simulated lattice, the team used a quantum gas microscope, producing over 35,000 images of individual atoms and their magnetic orientations. By varying the temperature and doping levels, the researchers directly observed how these changes affected electrons’ spatial positions and magnetic correlations.

“It is remarkable that quantum analog simulators based on ultracold atoms can now be cooled down to temperatures where intricate quantum collective phenomena show up,” said co-author Antoine Georges, director of the CCQ at the Flatiron Institute.

“Magnetic correlations follow a single universal pattern when plotted against a specific temperature scale,” said lead author Thomas Chalopin of the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics. “And this scale is comparable to the pseudogap temperature, the point at which the pseudogap emerges.”

Superconductivity Arises

Beyond the unexpected order, the observation also revealed complex multiple-particle structures rather than simple pair interactions. Previous work focused only on pair interactions, whereas the team’s recent research found that up to five particles can simultaneously affect one another. This new insight may be crucial in developing new models and better understanding how the pseudogap transitions into superconductivity.

“By revealing the hidden magnetic order in the pseudogap, we are uncovering one of the mechanisms that may ultimately be related to superconductivity,” Chalopin explained.

The researchers say that continuing work along these lines will have broader implications than just the study of superconductivity.

“Analog quantum simulations are entering a new and exciting stage, which challenges the classical algorithms that we develop at CCQ,” said Georges. “At the same time, those experiments require guidance from theory and classical simulations. Collaboration between theorists and experimentalists is more important than ever.”

The paper, “Observation of Emergent Scaling of Spin–Charge Correlations at the Onset of the Pseudogap,” appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on January 21, 2025.

Ryan Whalen covers science and technology for The Debrief. He holds an MA in History and a Master of Library and Information Science with a certificate in Data Science. He can be contacted at ryan@thedebrief.org, and follow him on Twitter @mdntwvlf.