The chin is one of our most familiar features, yet scientists still debate why we evolved it. Here’s a breakdown of what we know about it so far.

getty

Look at your face in the mirror, and you’ll see it instantly: the chin. This small, bony prominence at the bottom of our lower jaws is such a mundane feature that we hardly even notice that it’s there — until you realize that it’s actually one of the most remarkable anatomical mysteries in all of human evolution.

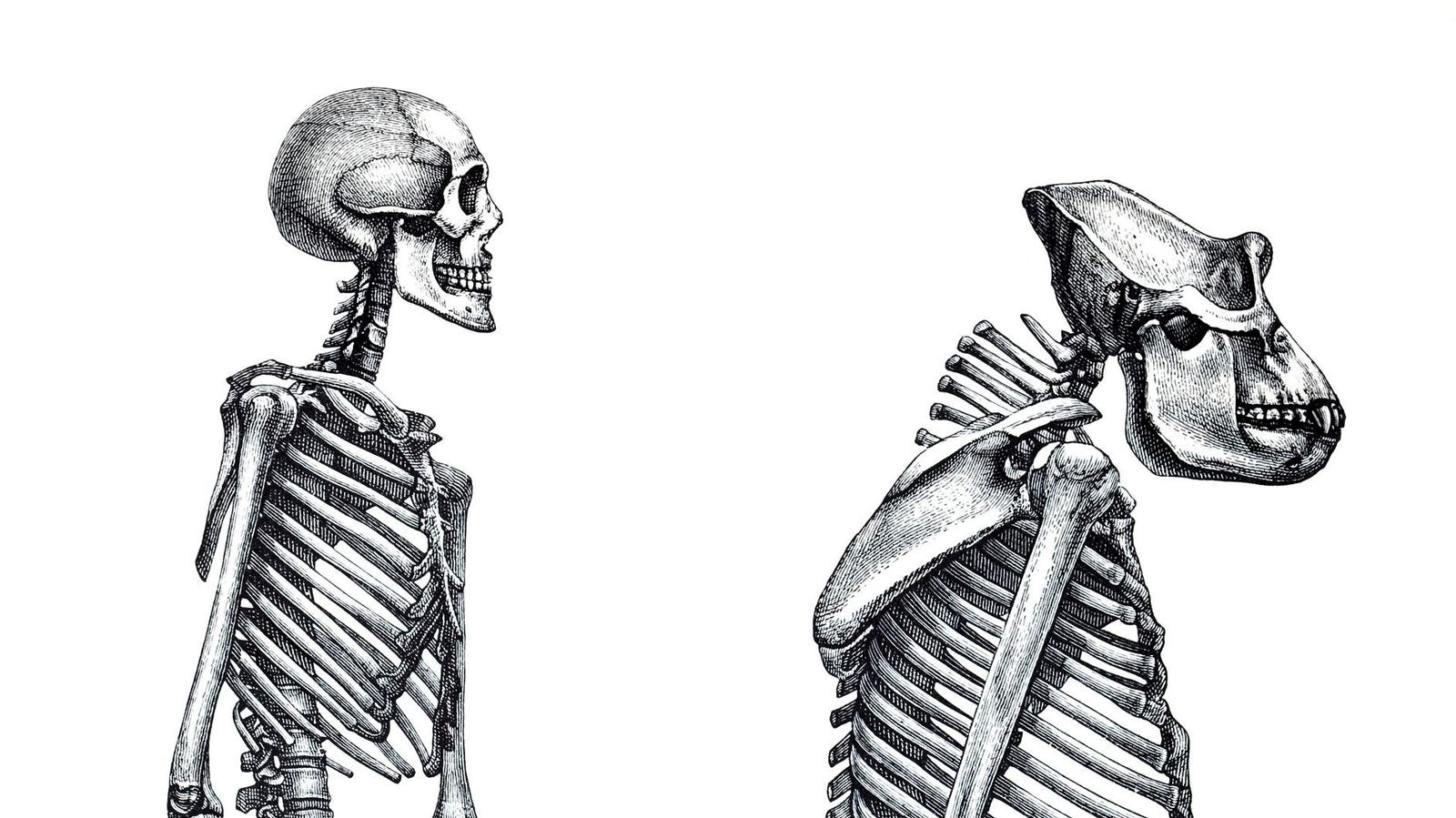

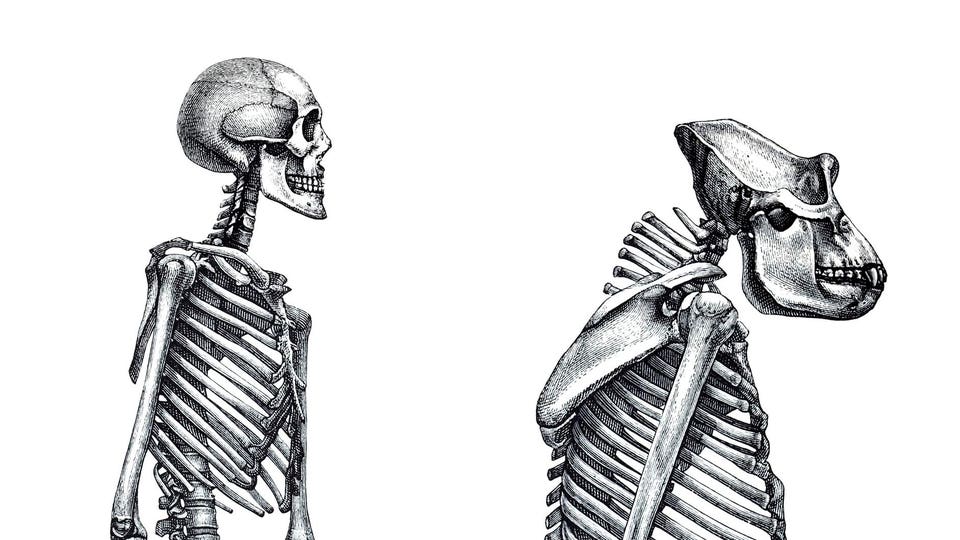

Modern humans, or Homo sapiens, are the only living primates with chins. Our earlier ancestors (like the Neanderthals, Denisovans and other extinct hominins) lacked the structure completely. And despite more than a century of academic debate, anthropologists cannot agree on a definitive explanation for why our species has evolved this trait.

Some hypotheses suggest the chin has a functional role; others propose that it’s a byproduct of changes in our facial structure. Here’s a breakdown of the leading scientific research on the matter, and why the debate persists today.

Why Do Humans Have Chins?

Other extant primates typically have receding lower jaws, without a distinct protrusion. Homo sapiens, however, exhibits a highly defined mandibular prominence: the bony chin. Fossil records reveal that this feature appears to have emerged relatively abruptly in anatomically modern humans, roughly 200,000 years ago. Notably, it is completely absent in our closest extinct relatives.

While this distinctiveness makes the chin a very useful marker in paleoanthropology for identifying modern human remains, it’s still very unclear as to what selective pressure actually brought it into existence. At present, there are three leading bioanthropological theories.

Theory 1: Human Chins Are Mechanical Reinforcements

Early explanations usually proposed that the chin evolved as a functional response to mechanical stress. That is, we evolved a reinforcement that helped distribute the forces of chewing more evenly across our lower jaw.

The logic behind this theory is sound in an intuitive sense: as our diets shifted over thousands of years, perhaps with tool use or cooking, our bite forces might have changed. This, in turn, might have favored certain structural adaptations, like the chin.

However, biomechanical studies have challenged this idea. A 2006 study from the Journal of Dental Research leveraged a computational modeling technique that simulates stress and strain on bones in order to test this. Surprisingly, the authors found that “chinned” and “non-chinned” mandibles actually showed similar strain patterns under biting loads. In other words, the chin contributes negligibly to resisting chewing forces.

Similar finite element work also indicates that while changes in symphyseal form can affect strain, they cannot do so conclusively in ways that would drive chin evolution solely for mastication.

In fact, developmental observations show that the chin becomes more pronounced after most chewing development ends (late in adolescence), which weakens claims that mastication is the primary driver. For these reasons, many researchers have started to reject this idea.

Theory 2: Humans Use Chins For Sexual And Social Signals

Another longstanding hypothesis is that chins emerged through sexual selection, or as a signal of facial aesthetics and hormonal cues. Indeed, some academics have argued that pronounced chins could perhaps serve as a signal for developmental stability or testosterone levels. This is something that could potentially influence an individual’s mate choice and reproductive success.

Although there is some evidence that chin shape can differ between males and females, linking this to evolutionary selection is pure speculation. Naturally, fossils have no way of directly telling us what our ancestors found attractive; this is something that makes all sexual selection hypotheses notoriously difficult to test in deep time. Nevertheless, the idea continues to be discussed in anthropological circles.

Theory 3: Chins Are A Byproduct Of Human Facial Retraction

Perhaps the most widely supported explanation among researchers today is that the chin is actually a byproduct of how the human face evolved, rather than an adaptation with a specific purpose.

This theory, as a 2015 study from the Journal of Anatomy describes, surrounds the fact that as Homo sapiens emerged, their faces became smaller and flatter over time, as compared to earlier hominins. Specifically, this process is what’s linked to our having smaller jaws, smaller teeth size and craniofacial restructuring.

In this framework, the chin isn’t argued as a trait that was selected for, but rather as one that emerged because so many other parts of the face were changing. It’s suggested that as the mandible shortened and the face retracted beneath the braincase, the lowest point of the jaw projected forward relative to the rest; this resulted in what we now recognize as the chin. This idea is supported by developmental evidence that shows human chins become more prominent when the face grows and reshapes during maturation.

Why The Human Chin Debate Endures Today

An important question to consider, especially in relation to the third theory, is what caused our faces to shrink in the first place. Some researchers suggest broad changes in human behavior (e.g., increased social tolerance, cooperation, etc.) could have influenced our hormonal profiles, like testosterone levels. This, in turn, could have impacted our craniofacial growth patterns.

This “self-domestication” hypothesis suggests that Homo sapiens underwent selection for reduced aggression, which then had cascading effects on our skull and jaw proportions. But as intriguing as this framework is, it also remains both highly speculative and difficult to test directly with fossil evidence. That said, it still poses a noteworthy idea: that chin evolution may be tied to social and developmental changes beyond mechanics alone.

Another question to consider is that if the chin truly doesn’t confer any significant survival advantage, then why has it persisted across all modern human populations? Some argue that once a feature emerges, it can become entrenched through genetic drift or cultural preference, even if it doesn’t serve a critical function anymore. We see this with anatomical features like wisdom teeth, the appendix and the tailbone, which aren’t relevant to modern-day humans.

While there still isn’t a true consensus on the matter, many believe that none of the working hypotheses fully explain the human chin. These individuals argue that the more likely reality is that there are multiple factors — developmental, functional, social, historical — that interplay in its origin. But, again, most of these hypotheses are almost impossible to test.

So why, after decades of research, is there still no agreement? Part of the reason is that evolutionary biology very rarely offers us clean answers. A trait can arise through chance, constraint and indirect pathways just as much as through direct positive selection. This means that the chin could even be an exaptation: a structure shaped by one set of forces, but maintained under different ones.

Anthropologists and biomechanists continue to refine models and compile comparative data from fossils, human ontogeny and biomechanics. New analytic tools may give us a clearer resolution. But until paleoanthropology can unpick the threads of facial evolution with greater precision, the chin will continue to elude us.

Curious how deeply your human identity is intertwined with the natural world? Take this science-backed test to see where you fall on the human–nature spectrum: Connectedness to Nature Scale

Ever wondered which animal best reflects your human instincts, values, and emotional patterns? Take this two-minute test to uncover the animal archetype shaping your human nature: Guardian Animal Test