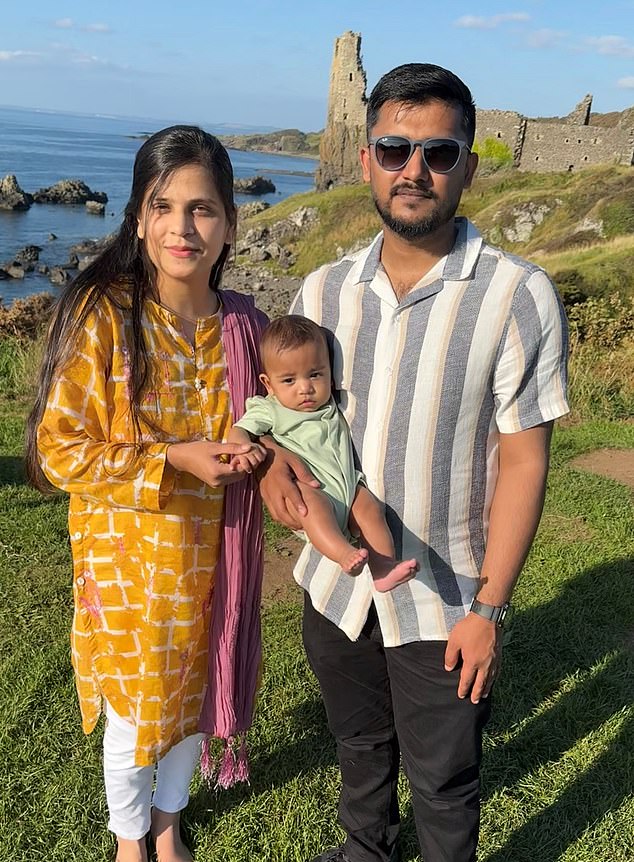

Like most new parents, Ahad and Hira Ul Hassan keep a close eye out for signs that their one-year-old son Zohan is developing just as he should.

But the couple, from Ayr in Scotland, have more reason than most to feel anxious about their child.

In March last year, little Zohan – then just eight weeks old – underwent surgery for a hernia on the right side of his abdomen. His parents weren’t unduly worried; weeks earlier, he’d undergone the same operation – with no complications – for a hernia on his left side.

But this time doctors at the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow made a catastrophic error that could potentially damage Zohan’s health for life.

Instead of injecting him with 2ml of paracetamol to dull the post-operative pain, they gave him 20ml – ten times as much as they should have.

Ahad received a call from the doctor, who said his son had accidentally been given a potentially fatal dose of paracetamol – and he should get to the hospital straight away. He recalls: ‘I rushed out of work and to the hospital; I found Hira so distraught she couldn’t talk.’

Doctors noticed the error immediately on the operating table – and Zohan was quickly treated with acetylcysteine, which blocks paracetamol’s toxic impact on the liver. Regular blood samples were taken to measure how much of the drug was in his system.

But despite quick action, the concern is that harm was already done.

Hira Ul Hassan with Zohan. After a routine operation for a hernia, doctors accidentally gave him a 20ml injection of paracetamol – ten times as much as they should have

Even though Zohan survived the overdose, doctors have warned it could lead to physical or mental long-term problems

While there was no obvious tissue damage and liver scans showed it appeared unscathed (acute liver failure is a common cause of death in paracetamol overdoses), doctors have warned Ahad and Hira that there’s still a significant chance Zohan may suffer as yet unknown physical or mental long-term problems.

The true impact will only become clear as he gets older and is expected to reach milestones, such as crawling, sitting up or saying his first words.

‘It’s horrible – we potentially have years of worry ahead,’ says Ahad, 27, an engineer.

‘So far, he is developing, but not at the same rate as other infants his age. At nine months old, he wasn’t crawling or trying to sit up – and there are some concerns about his eyesight. Doctors have said they don’t know what the future holds for him.’

Deliberate (and accidental) paracetamol overdoses at home have long been a problem.

It’s the reason why, in 1998, the Government introduced legislation restricting over-the-counter pack sizes of the drug to a maximum 16 tablets – and you can only buy two packets. But accidental paracetamol overdosing of NHS patients by medical staff, as in Zohan’s case, seems to be an emerging significant problem, too.

In April last year, Emma Whitting, senior coroner for Bedfordshire and Luton, issued a Prevention of Future Deaths (PFD) report to Bedford Hospital following the death of a 72-year-old woman from liver failure in September 2023, when she was given too much paracetamol by staff.

PFDs are issued when coroners believe that action should be taken to prevent future deaths. They act as a red alert to others about the dangers.

Doctors told Ahad and Hira that they don’t know what the future holds for Zohan

Accidental paracetamol overdosing of NHS patients by medical staff seems to be an emerging significant problem

The coroner noted how Jacqueline Green had been admitted to hospital after falling at home. Frail, weak and dehydrated, Jacqueline was given 1,000mg of paracetamol four times daily – a standard adult dose – by a junior doctor, to ease pain from the fall.

But the medical team had made a critical mistake.

NHS guidance states paracetamol doses should be reduced by at least a third in patients weighing less than 50kg (7st 12lb), as they are likely to be malnourished to the point where their body does not metabolise the drug properly – so more of it ends up deposited in the liver, where it can cause fatal toxicity.

NHS guidance also states that all visibly frail patients should be weighed on admission to check if they are under 50kg. Yet nobody in the hospital checked Jacqueline’s weight for two days, during which time staff carried on giving her the 1,000mg dose four times a day.

When she was finally weighed, it was found that she was, in fact, just 33.6kg (5st 4lb). And even then, it was another 24 hours or so before staff halved her paracetamol dose.

Less than a week later, Jacqueline died in hospital from liver failure, brought on by toxic levels of paracetamol in her system, the coroner ruled.

Bedford Hospital says it has now introduced protocols to ensure underweight patients get reduced doses of paracetamol.

Yet these are far from isolated cases, according to a 2022 investigation by the Health Services Safety Investigations Body – a government body set up to probe concerns over patient safety.

In a report on the investigation, it described in detail the story of an elderly female patient, identified only as Dora, at an unnamed NHS hospital.

Aged 83, she was admitted to hospital after a fall at home – and was given 1,000mg of paracetamol four times a day for knee pain she’d suffered as a result.

Dora was in hospital for 12 days before staff weighed her. She was just 40.5kg (6st 5lb) and lost several kilograms over the following fortnight.

Yet staff did not reduce her 1,000mg drug dose until she had been in hospital for 29 days, by which time tests showed she had dangerously high amounts of the painkiller in her bloodstream.

Doctors immediately started to treat her with acetylcysteine. But to be fully effective, this must be initiated within eight hours of the overdose occurring.

It was too late and Dora died the next day. An inquest concluded her prescription of paracetamol was ‘higher than it should have been and this played a part in her death’.

The probe by the Health Services Safety Investigations Body found that staff at the hospital, as well as at several others it investigated, did not routinely consider weighing patients before giving them paracetamol a priority.

It said: ‘Some staff said they believed that it is possible to estimate a patient’s weight by visual assessment. But the research evidence has found that this is not a reliable method.’

It said hospitals should make more use of technology to reduce the risks.

This includes software which blocks authorisation of a prescription drug’s use unless the patient’s weight has been entered into the system first. It would then dispense an appropriate dose. And there are ‘smart’ hospital beds that automatically weigh the patient when they lie on them. (It acknowledged that these are expensive, with such high-tech beds costing up to £14,000 – more than double that of a standard NHS bed.)

The report concluded: ‘Our findings will increase awareness of the potential for paracetamol toxicity in adults with low bodyweight. And some of the conclusions may also be applicable to other medications that have the potential to cause harm in underweight patients.’

Scientists have known for decades that paracetamol, although a very effective form of pain relief, in large amounts is toxic – especially to the liver, as it destroys the structural integrity of liver tissue and kills liver cells rapidly.

After the initial emergency treatment with acetylcysteine, Zohan was kept under observation and eventually discharged after three weeks with no further treatment.

The hospital carried out an internal probe which revealed doctors had mistakenly filled a 20ml syringe – rather than a 2ml syringe – with liquid painkiller.

Hospital chiefs acknowledged that staff had failed to properly check Zohan was getting the right dose.

In a statement to the Daily Mail, Dr Claire Harrow, deputy medical director for acute services at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde – which oversees the Royal Hospital for Children – said: ‘We would once again like to apologise to the family of baby Zohan. A Significant Adverse Event review was conducted into this case and the findings shared with Zohan’s family.

‘An offer of a follow-up meeting was made and we are in the process of making suitable arrangements with his parents.’

But Ahad, who is now pursuing a legal case against the hospital, feels the couple have been left out in the cold.

Other than the promise of a second MRI brain scan when Zohan turns one, he says they’ve received little in the way of guidance on what signs of damage to look for, or when to seek help. ‘We feel like we have just been left to deal with it on our own,’ he says.

After the mistake was first spotted, and Zohan was moved to a ward for treatment, his parents noticed he was making seizure-like ‘jerky’ movements with his body. ‘He hasn’t had any more seizures since, but we are constantly looking out for them. I know accidents happen but I’ve lost all trust in the NHS after this.’