At a public meeting last week (20 January) the founder of John McAslan + Partners showed off his rival design – a proposal billed as a ‘less disruptive’ alternative to plans submitted by ACME, which feature an 18-storey office tower erected above the station’s listed concourse. This contentious enabling commercial scheme will help fund major improvements to the busy London terminus.

During the event, McAslan told the audience that ACME – whose application continues to attract objections ahead of a City of London planning committee on 10 February – should have done more to question Network Rail’s brief.

Working with engineer Expedition and campaign group SAVE Britain’s Heritage, McAslan claims his concept would result in almost no demolition of the Grade II-listed 1990s station concourse.

He envisages a nine-storey development, inspired by the station’s Victorian railway architecture, hung from a lightweight steel arched frame and feature cross-laminated timber floors to float above the existing trainshed and platforms. McAslan has previously claimed the low-carbon design would cost ‘half the current £1.2 billion ACME scheme, take up two-thirds of the area, and take half the time to be delivered’, thanks to its anti-demolition and lightweight construction approach.

Speaking at the packed event held in John McAslan + Partners’ Farringdon-based studio, McAslan said: ‘I don’t like criticising other architects, particularly people like ACME, who are good architects, but I think their brief is completely wrong and they haven’t been able to challenge it.

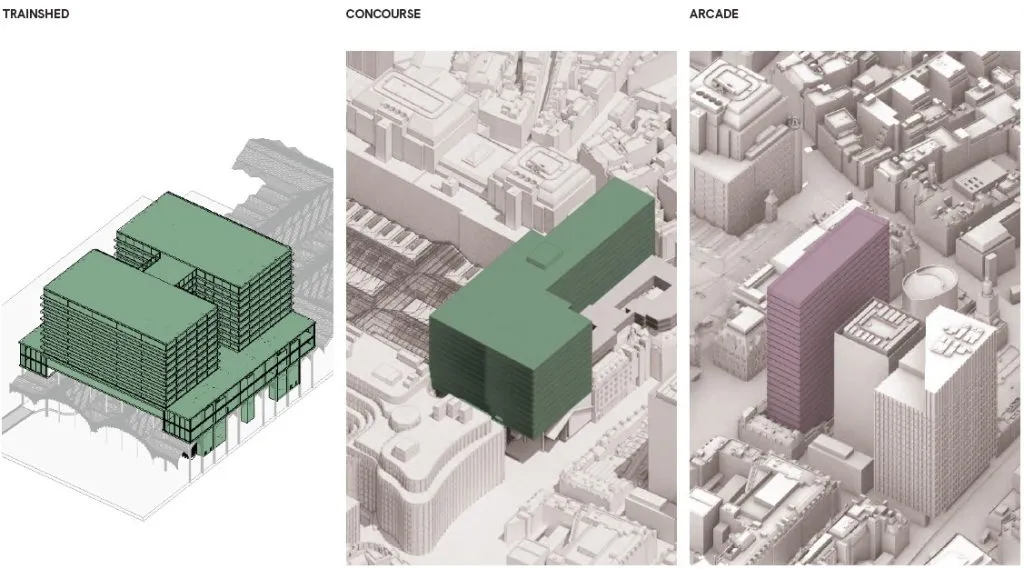

SAVE’s alternative Liverpool Street scheme (John McAslan + Partners)

‘That is a very hard thing if you’ve been presented with a vision [by Network Rail]. In retrospect, they might have wanted to do that [challenge it]. Maybe something else might have emerged.’

He added: ‘We’d be happy to collaborate. ACME could do [the new approach], I don’t mind. As long as something else happens.’

Supporters of his rival proposal include Griff Rhys Jones, the chair of the Victorian Society which is leading the Liverpool Street Station Campaign (LISSCA), a group of mainly heritage bodies opposing major redevelopment of the terminus. The famous comedian claims ACME’s ‘destructive proposals […] would plunge passengers into years of disruption’.

However, ACME’s Ludewig has hit back at McAslan, saying the idea of building over the trainshed had been his preferred option too but, after extensive examination, the concept was found to be unviable. He said others, including BIG and Herzog de Meuron, had also previously considered this approach and not progressed their schemes either.

Talking to the AJ, Ludewig said that, after spending considerable time trying to make a similar proposal work, the ACME team eventually ruled out the over-platform approach, blaming its ‘engineering complexity, its impact on the operation of the train services and its limited potential for a viable office entrance’. It was also deemed not to generate enough money to pay back any development partner as well as delivering the changes needed throughout the station.

Ludewig also said he had talked to McAslan, who oversaw the revamp of King’s Cross Station and Sydney Central, about ACME’s efforts to get a building over the trainshed to stack up commercially. In the end, he said, the pair had disagreed about whether such a scheme was viable.

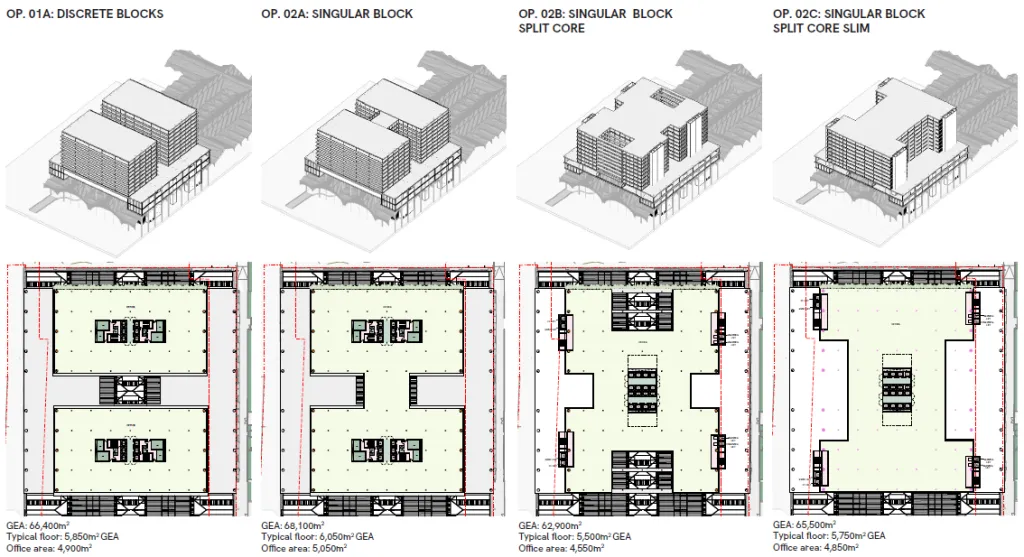

ACME’s optioneering for Liverpool Street – building over the concourse is the option submitted

The architect told the AJ: ‘[Our] trainshed proposal and John McAslan’s concept are nearly identical. The principles are 95 per cent the same.

‘I’ve invested a year of my life trying to get a building over the trainshed to work; it was an obvious idea. We spent significant resources investigating the technical constraints – with a lot more commitment than previous attempts – to either prove or disprove the practicality and viability of this option.

‘For a long time this was our preferred option and we included significant detail on it in our planning submission to explain why we ultimately had to adopt a different approach.’

Ludewig (see full comment below) said that ACME had interrogated a range of engineering options, including incorporating a supportive arch-like structure similar to the nearby 1990s SOM-designed Exchange House – a building which John McAslan’s scheme references.

However, he added: ‘Even if it is technically possible[…] if it doesn’t make any money, nobody would build it. Ultimately, the trainshed options died the death of being unviable.’

ACME’s floor plan options for building over the trainshed/platforms

Network Rail added that they had carried out several independent reviews of McAslan’s plans and had also come to the conclusion the alternative trainshed scheme was unviable.

ACME’s scheme, like the earlier one by Herzog & de Meuron, has faced criticism on environmental, heritage and viability grounds. It features staggered garden terraces sitting above the station, and would involve remodelling of the concourse, accessibility improvements and vaulted brick arches at two entrances.

The number of official objections to the ACME proposal has now topped 2,400, compared with around 1,100 letters of support.

Among those objecting is Tim Walder, the former principal conservation officer to the Greater London Authority. Describing the scheme as ‘physically and visually domineering’, he asserts: ‘The proposed office building is too tall and massive for this context. The 1985 to 1992 elements, listed only recently, are almost wholly destroyed.

‘The proposals also cause a high level of harm to the Great Eastern Hotel […] this elegant building will be backdropped and visually overwhelmed by the proposed offices.

‘The City should pause this scheme and think again.’

The planning officers’ recommendations ahead of next month’s planning committee meeting have not yet been published.

ACME’s proposal: new pedestrian routes to Exchange Square

Friedrich Ludewig, founder of ACME: why building over Liverpool Street station’s trainshed is not viable

A number of architects have independently proposed options to build over the trainshed – Herzog de Meuron with Sellar, BIG with British Land, and ACME with Network Rail.

I’ve invested a year of my life trying to get a building over the trainshed to work – it was an obvious idea. We spent significant resources investigating the technical constraints – with a lot more commitment than previous attempts – to either prove or disprove the practicality and viability of this option. For a long time in the option assessment, this was our preferred option, and we included significant detail on this option in our planning submission to explain why we ultimately had to adopt a different approach.

We’ve spoken to Historic England and the City of London about this option, exploring options for column positions, entrances, bulk and massing.

The ACME trainshed proposal and John McAslan’s concept are nearly identical. The principles are 95 per cent the same – but we have had a lot more time to investigate the details, so we differ when it comes to entrances, column detail and construction logistics, where our proposals are a bit more realistic, consider logistics, buildability alongside an operational solution.

Practically, if you wanted to create an arch from which the rest of the structure is hung (similar to SOM’s Exchange House to the north) you would have to first build a temporary transfer structure to build this arch. This is how SOM built Exchange House. That would mean swinging steel across the live platforms 1 to 10.

Network Rail Anglia route has been very clear, that is not acceptable. You cannot simply close 10 platforms in the UKs busiest train station and, even if that level of passenger disruption was acceptable, it would add considerable cost. For this reason, our structural team discarded the arch form and considered a transfer structure, which would require landing columns protruding through the original Victorian trainshed down to platforms, additional to the cores for the office building, required in any scenario.

Daylight is also complicated. The station is surrounded by very deep plan office buildings, on Bishopsgate and Broadgate. We decided to create massing options that never get closer than 12m to a neighbouring office building before stepping back. The McAslan scheme is much closer; it’s basically within touching distance of 135-155 Bishopsgate. We don’t think you can build so close to a deep 1990s building. We’d be taking away the only daylight they have.

But it doesn’t really matter. Even if it is technically possible – and from an engineering point, many things are possible – if it doesn’t make any money, nobody would build it. Ultimately, the trainshed options died the death of being unviable.

We explained to John McAslan and Chris Wise [of Expedition Engineerig] in detail the work that ACME had done with WSP, AKT2 and AECOM. Gleeds and JLL. And we explained why the scheme failed. They agreed that the schemes are very close. However, they refused to accept the results of the viability assessment, and the concerns from the Network Rail Operations team.

The proposal to build over the trainshed failed because we could not make any money. It would cost £600 million to build and even in the most optimistic scenarios it would not create enough residual land value to pay for the station improvements and cover the margins needed for any development partner to deliver it.

SAVE’s alternative Liverpool Street scheme (John McAslan + Partners)

Chris Wise, senior director at Expedition Engineering: how we would do it

Our engineering would bridge the main Victorian trainshed without touching it, efficiently supporting the clear span of 90m with a series of tied parabolic arches, rather than the heavy transfer trusses often used for air rights projects.

Inside the new building, instead of heavy columns, our floors are hung from the arches. All is carried on a series of tall piloti columns, designed at a civic scale to land away from the twin roofs of the Victorian station structure.