Steve was at home in Oxfordshire four years ago when his phone pinged with a video message from his daughter Joni. She was rarely in contact these days, so he quickly pressed play. “It was horrendous,” he recalls. “Joni looked awful, her face was drawn and she was looking at the camera making all these accusations of all kinds of abuse that I was meant to have done to her when she was two years old.”

Steve called her immediately and sent several messages. He desperately wanted to talk to his daughter, to tell her that this abuse had never happened, but Joni wouldn’t answer. “I got all the family together then and showed them the video. They couldn’t believe that Joni was saying this,” he recalls. “It devastated the family, absolutely devastated us.”

Steve holds one person to blame: a therapist whom Joni began seeing after she left home in her early twenties. Until then, Steve says, the family had been tight. But shortly after the therapy began, Joni told her parents she needed space. “She’d give us excuses that she was busy, that she couldn’t meet up,” Steve says.

It was strange behaviour, out of character, but they dismissed it as Joni growing up and seeking independence. In fact, “she was being brainwashed”, he says.

Within two years Joni was in thrall to her therapist, Rebecca, and had rinsed her savings on sessions with her. Next Joni cut off all contact with her friends and family and moved away without giving an address.

Out of despair, Steve and his wife read the journal Joni had left behind in her old flat. “We weren’t going to but we wanted to know what had happened,” Steve says. It contained details of intense, unorthodox therapy sessions, of Rebecca’s suggestion that there was buried trauma in Joni’s past.

“We looked up this woman’s website and it said all this stuff about how your mind has to heal your body. And if you have any buried traumas in your life, we will find them.”

Steve is adamant he never abused his daughter and believes that Rebecca was determined to reveal buried memories of abuse, whether or not they existed. “I had no idea someone could do this. This therapist has ruined our family’s life. I used to be an outgoing person; now I’m a shell.”

Steve sought advice from the London-based Cult Information Centre, a charity that helps people affected by the type of brainwashing that goes on in cults. They suggested all the family could do is wait for “her lightbulb to come on” — the pivotal point when an indoctrinated person begins to question their new belief system.

However, Steve and his wife felt useless just waiting. Two years after the video message they tracked down an address for Joni and waited outside. After several hours she came around the corner. “Her face was like thunder when she saw us but she said, ‘You’d better come in,’ ” he recalls. “She had nothing — just clothes and a bed, not even a kettle. Then we were all in tears, weeping. But we didn’t say much because you have to tread really, really carefully.”

It was too much for Joni. After meeting for a coffee the following day, “she burst into tears, said, ‘I can’t do this,’ and ran off. And that was it,” Steve says. His daughter “felt like a total stranger”.

Steve and his family are not alone in this situation. Last year the podcast series Dangerous Memories by Tortoise Media investigated a London-based life coach called Anne Craig who, it was alleged, had made several young women believe horrific, untrue things about their parents via therapy sessions, leading them to cut themselves off from friends and family for years.

After it aired, a number of other parents came forward with accounts of similar experiences with different psychologists and therapists. The podcast producers put them in touch with me. Steve — not his real name — was one of them. Except for one family who have been reunited, none wanted to be identified. They were worried exposure would further drive away their estranged daughters. All said they had been happy families and that the accusations of abuse were entirely unfounded. Each parent expressed horror and bafflement that therapy could turn so manipulative and abusive, and that they had no legal means to stop these rogue therapists. They wanted to know what could be done to change that.

The life coach Anne Craig outside the High Court in 2016. She denies manipulating clients including Hue

PAUL KEOGH

The problem with therapy

In the UK therapy is booming. Nearly a third of adults have sought help from a counsellor or psychotherapist in the past year, according to a YouGov survey commissioned this year by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), which found that 75 per cent of people who have had therapy would recommend it to someone struggling with their mental health.

It is widely acknowledged that therapy can be incredibly beneficial, life-saving even. Yet a therapist-patient dynamic is unique and vulnerable to abuse. For many people, their therapist is the person they trust most.

What many people who sign up for therapy don’t realise is that, unlike other healthcare roles, there is no statutory regulation of the profession in the UK. NHS practitioners must be registered, but in private practice “psychotherapist”, “psychologist”, “psychoanalyst”, “hypnotherapist”, “therapist” and “counsellor” are all unprotected terms — meaning anyone without any form of qualification can set themselves up as one tomorrow, with a plaque on the door. This excludes “clinical psychologist”, “counselling psychologist” and some other titles, which are statutorily regulated, and art, drama and music therapy, which are regulated professions.

There are several professional bodies — of which BACP is the largest — that require a minimum amount of training to join and have a non-legally binding complaints procedure, but it is up to the individual practitioner if they want to accredit themselves. There is no law to stop a therapist from continuing to practise even if they are struck off a professional register after misconduct; and they are under no obligation to report this to their patients.

The UK is unusual in this. Therapists in every state in America must have a licence. In Europe, the European Certificate of Psychotherapy is often demanded from practising therapists, while countries including Germany, France, Italy, Sweden and the Netherlands all require training and registration in psychotherapy.

There are of course many private unregistered therapists in the UK who are ethical and very good at their work, but there are some who are the opposite.

The idea of uncovering buried or repressed memories of trauma is not new. It took hold in the 1980s when increasing numbers of people began to claim that in the course of psychotherapy they had unearthed memories of childhood sexual abuse.

Some experts were sceptical and began to investigate whether therapists were inadvertently implanting false memories of childhood trauma in clients through suggestive techniques, memories in which the person came to believe fully. A key sceptic was the American psychology professor Elizabeth Loftus, whose studies have found that, through guided imagery, dream analysis and suggestion, patients can become convinced that they suffered deeply traumatic events in childhood that never happened. Others, especially therapists, stood by the validity of these recovered memories: the debate was dubbed “the memory wars”.

The psychologist Elizabeth Loftus’s studies have shown how memories can be manipulated

GRAEME ROBERTSON / EYEVINE

The American Psychiatric Association went on to warn that “recovered” repressed memories in which the person believes strongly were often not true. Former clients began suing their therapists. In a landmark case in 1995, a jury in Minnesota awarded $2.6 million to a woman who claimed her psychiatrist told her that if she recovered her buried memories she would discover that she had been sexually abused by relatives.

In Britain in 2017 the British Psychological Society published an article saying “there is now widespread agreement on the existence of false memories of sexual abuse and on the immense harm they can cause”.

In 2019 a group of memory scientists in America, including Loftus, concluded that therapists were still using techniques that had the potential for creating false memories, “potentially leading to false accusations”.

Known as false memory syndrome, it remains highly controversial, with survivors of sexual abuse saying that it can be used as a get-out by perpetrators in genuine cases.

Peter Naish, a psychologist and former president of the section for hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine at the Royal Society of Medicine, is in no doubt that the syndrome is real. “It’s not unusual that therapists do think there is probably something lurking in your past,” he says.

They are not implanting false memories deliberately, he says, but “it’s very dangerous and the effect can be devastating. It feels entirely like a memory — [the clients] ‘remember’ it clearly, so they are deeply affronted when a person suggests it might not be true. If the alleged perpetrator denies it, then yes, the chances are they will cut them off.”

The indoctrination of Hui Hue

Sarah Strutt’s daughter Hui Hue stopped replying to her messages shortly after she began therapy sessions with Anne Craig in 2010. Strutt didn’t yet know it, but Hue had come to believe that she was the victim of extreme sexual abuse in childhood and that her mother had been at the centre of it all. All Strutt knew was that she was losing her daughter. “I was always trying to hang on, not trying to be too pushy. But she was slipping away.”

By 2012 Hue had cut her off completely. Strutt “ambushed” her daughter on three occasions after this, demanding to know what was going on. None of them went well. “It was agony. Every morning it was like waking up in a vat of black oil,” Strutt says softly. “But I never gave up hope; you can’t live without hope.”

Eventually Strutt learnt from another family — whose daughter was also a client of Craig — about the allegations of abuse. For years Strutt had no idea where Hue was, but the lightbulb moment came in 2017.

Hue as a child

COURTESY OF HUI HUE

Pregnant with her first child, Hue agreed to meet her mother in a café in Brighton. It was the first time they had seen each other in more than three years. “My heart was in my mouth but I stayed calm and just listened to her,” Strutt says. Until at one point Hue brought up the sexual abuse.

“I said she had to accept that false memories had been planted and it all blew up,” Strutt says. “Hui started screaming that it was a waste of time.” Strutt managed to calm things down, telling Hue that although she didn’t have a right to tell her what had happened, she just didn’t remember it that way herself.

Today Strutt, 70, is sitting next to Hue, 38, at the table of Hue’s kitchen in Lewes, East Sussex, patting her daughter’s golden retriever. She and Hue are now in contact every day but it took a long time for them to get to this point of reconciliation.

Over rooibos tea, Hue tells me she first met Craig shortly after she had finished her training as a portrait artist at the prestigious Charles H Cecil Studios in Florence. She had moved back to London and was feeling vulnerable, “lost in this massive pond”. Friends who were clients of Craig extolled her powers of spiritual therapy. They told Hue that Craig could “see things in yourself that you couldn’t see”. She made an appointment.

Sessions at Craig’s house in Camberwell cost £90 and almost always ran over the therapy standard of 50 minutes. Hue began to see her weekly. They were also in regular contact outside of sessions. Craig would, Hue claims, ask her to draw and write down her feelings using her left hand (she is right-handed) and later burn these pictures. She would also tell Hue to write down her dreams when she woke up so Craig could interpret them.

Hue didn’t recognise the red flags. Why would she? She was young and had never had therapy before. “To me it was just lovely that the sessions were so long, that she was in touch with me outside of them,” she says. “Looking back I can see that even the first chat was weird. Immediately she made me feel she knew things about myself that I couldn’t access. She had the power and I wanted to please her.”

Craig’s interpretations of what had gone on in her past got darker, Hue claims. “If I told her that I didn’t believe something could have happened to me she’d ask me what I was avoiding, lead me back towards what she wanted me to believe.”

Hue began to think that she had repressed memories that involved gang rape, paedophile rings and murdered children. “Craig forbade me from telling my family what she was discovering in these sessions — the rule was never confront them, never tell them,” she recalls. “I was terrified. The abuse I was believing was really severe.”

Craig vehemently denies implanting false memories into Hue or any client.

Hue says her dependency on Craig grew and eventually she cut herself off from family and friends and disinherited herself — without explaining why. “I was stripped of every pleasure and every joy,” she says. “It got to the point where I needed Anne’s permission for absolutely everything. I was like a very fragile child who couldn’t make any decisions.”

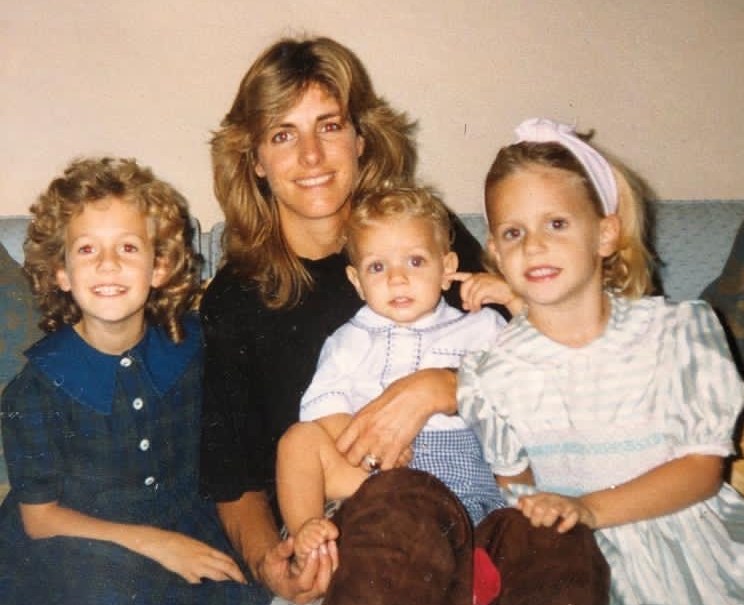

Strutt with Hue, right, and her siblings, Charles and Sophie, c 1992

COURTESY OF HUI HUE

The unravelling

Craig had no formal training or qualification to deal with the issues that arose in her sessions with Hue. Her professional background was as a development coach for companies. In 2014 lawyers acting for the family of another of Craig’s clients wrote to the life coach demanding that she stop planting false memories in their daughter. Eight months later Craig was arrested for fraud and for causing psychological harm, though the latter charge was dropped. She spent six months on bail — and, crucially, was not allowed contact with Hue and the other young women who were her clients. In 2015 the CPS decided not to pursue the case.

For Hue the sudden loss of contact with Craig was torturous, but in hindsight she believes that being forced back out into the world was what she needed. She went out busking and started talking to people again. Doubts began to set in about Craig. “Isolation is so powerful. When that’s not there, it doesn’t have that same grip on you,” she says.

Lawyers for Craig deny all these accusations. “These allegations have been presented to Mrs Craig on a number of occasions and on every occasion have lacked supporting factual evidence. They are, and always have been, considered by Mrs Craig to be malicious and intended to cause Mrs Craig harm and damage.”

Hue — who has changed her name by deed poll — now has two young children and is working as a portrait artist and musician. She is still fragile, still rebuilding herself, and finds it overwhelming to talk about the years of damaging therapy. She has been diagnosed with PTSD. “The big abuse stuff like the paedophile ring fell away quickly, but then you have to sort out what memories are real and what you actually know,” she says.

For years, she says, she felt “like I must have been sexually abused because I feel so much pain. That was the conclusion that fitted most. Because what bigger validation is there for your suffering?”

A social psychologist who specialises in helping people who have left cults later explained to Hue that this was very normal. “A lot of people can attach that solution to feelings of emptiness or pain, she told me. But I’d still say to Mum stuff like, ‘I trust you but I just need to know, did you ever sexually abuse me?’ And I saw in her eyes that she didn’t. But I’m still unpacking the whole thing today. It’s so toxic.”

LAURA PANNACK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Should there be tougher laws around therapy?

Strutt and others are campaigning for a change to the law — Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015, which criminalises coercive or controlling behaviour within intimate or family relationships. They want it widened to include therapists and counsellors. As it stands, it is a crime for a parent or partner to commit this kind of abuse, but not for a therapist.

Four years ago, Lord Marks of Henley-on-Thames tried to introduce such an amendment. It didn’t get through but, he says, there was plenty of crossbench support. In the face of numerous accounts of fake-memory hucksters, he believes it is urgent. “Often it is financially led,” he says. “Where therapists — or so-called therapists — can alienate children from their families, they can exercise a great deal of control and charge a lot of fees over a long period because they increase the dependence. It’s a form of transference.”

Marks and others — including Jonathan Coe, a specialist in professional regulation — are also trying to introduce statutory regulation of therapists and mental health professionals. Voluntarily signing up to professional bodies isn’t enough, they say. It doesn’t necessarily get rid of bad or incompetent therapists and it isn’t easy for people to differentiate between someone who is well qualified and someone who isn’t.

The government has resisted calls for statutory regulation, urging people to use qualified practitioners accredited by the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care.

The parents I spoke to felt powerless to stop their daughters from being manipulated by their life coaches or therapists — as long as their daughters were seeing their therapists, they couldn’t do anything. Each was waiting for the lightbulb moment.

Steve is hopeful that Joni’s might arrive soon. Recently Joni got back in contact with her sibling and, to everyone’s surprise, turned up at a party. “She was talking to everybody, laughing and joking, but not to me and my wife,” Steve recalls. He tried to speak with her, to tell her these accusations weren’t true. All she would tell him was, “Dad, I didn’t have a choice.”

Then earlier this year the family visited Joni, with her permission. “It went well — much better. We saw each other a few times,” he tells me. “We know it’s going to be very slow. We don’t want to put pressure on her, but we are still hopeful she will come home to us.”

The real names of Steve, Joni and Rebecca have been changed