‘It’s a staggering achievement, helped partly by Solbrekken’s having written two previous Flagstad books and being an expert in Second World War Norwegian history, as well as being a playwright’

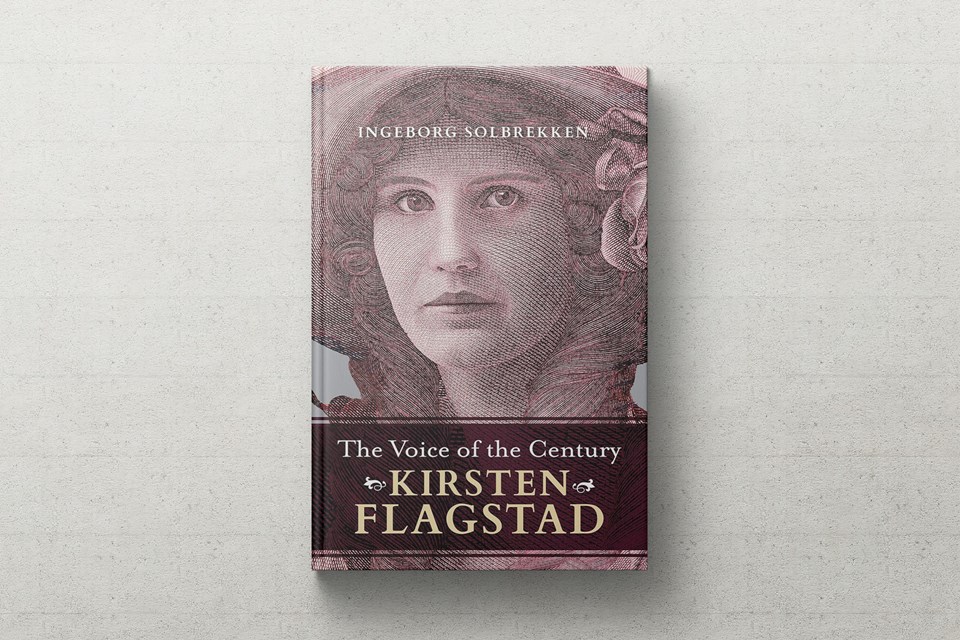

The Nazi Nightingale? They actually called her that? Most Wagnerians know that the great soprano Kirsten Flagstad had some rehabilitation challenges after the Second World War. But the cruel, protracted post-war accusations encompassed the years for which she is now best remembered, as documented in detail in this newly translated book. Though all periods of Flagstad’s life are touched upon, Ingeborg Solbrekken’s emphasis is on the psychological threads and social context that led to Flagstad’s vilification.

Why this book? Why now? In the past decade or so Flagstad’s discography has emerged with greater clarity, thanks to modern remasterings, warranting a renewed curiosity about the story behind the rich, huge voice that, as late as the 1958 recording sessions for Das Rheingold, left the Vienna Philharmonic and Georg Solti astonished. Much of this information has been around for years – the book itself was first published in 2021 in Norwegian – but the contextual understanding is new. Also, the kind of disinformation wars that swirled around Flagstad during the years of her best singing now mirror our 21st-century world more than ever. Then there are the questions about staying or leaving one’s home in the face of unsympathetic politics.

Flagstad (1895-1962) was an easy target. Her young-adult self would have been happy to be a stay-at-home wife and mother in Norway, but she sang operetta for reasons more financial than inspirational. Oslo was far from the cosmopolitan centre that it is now. Yet with prodding from her mother and second husband, she found herself at the age of 40 becoming – almost overnight – far more than the most famous opera singer since Enrico Caruso. After promising encounters with the Bayreuth Festival, the Metropolitan Opera more or less threw a net over her. Following her 1935 debut, she was credited with saving the financially beleaguered Met and giving inspiration to Depression-era America. It helped that a number of great Wagner singers (some Jewish) had fled Europe and landed at the Met – Alexander Kipnis, for one, who also helped make contacts for Flagstad before leaving Europe. Surrounded by dream-cast colleagues, Flagstad was the linchpin of what is now considered a Wagnerian golden era. Her fame was unprecedented, as was her visibility.

This is where Solbrekken’s story departs from the usual perception of Flagstad’s life from 1935 to 1941. Those six years that changed the music world were more fraught than blessed for her. The schedule of huge Wagnerian roles and concerts, every two or three days, seems not to have taken the slightest toll on the voice but taxed everything else – her mental and physical health, duty to family – to its limits. She had the most strictly guarded dressing room in the opera world after performances, when she needed ample time to decompress. Her world was clearly circumscribed and shut out knowledge of what was going on around her, and eventually what was happening to her. Consequences were particularly steep when Norwegian diplomats were turned away from meeting her. Being the greatest international celebrity from Norway since Viking explorer Leif Ericsson, she faced extramusical expectations she couldn’t or wouldn’t fill. Disappointment – and a sense that she wasn’t a proper Norwegian – fuelled later subversive smear campaigns.

Two major characters come into play at this point in the story: Flagstad’s second husband, the industrialist Henry Johansen, who was not the most beloved public figure in Oslo, and Norwegian ambassador Wilhelm Munthe de Morgenstierne, who felt repeatedly snubbed by pre-war Flagstad (Solbrekken characterises him as a narcissist) and played up her German-language repertoire after her country had been invaded by Hitler. Husband Johansen gave her detractors plenty of fodder with accusations of profiteering from Nazis, even though he later funnelled such profits to resistance fighters. The tipping point was Flagstad’s return to occupied Norway at Johansen’s insistence. In doing so, she spent the war years disappearing into rural Norway and otherwise ducking demands for her to sing at Nazi events. Johansen was in and out of jail in the years before his death in 1946. She narrowly escaped trial, was stripped of everything she owned and, upon returning to New York financially destitute, faced booing audiences and accusatory Walter Winchell columns full of falsehoods supplied by the Morgenstierne-dominated Norwegian embassy. Some of the more outrageous stories had Flagstad flying in Hitler’s private plane. Meanwhile, musicians with proven Nazi affiliations were breezing into New York without harassment.

It’s here that Flagstad becomes a modern counterpart to the Old Testament figure of Job, right down to the skin sores that, in her case, came from painful psoriasis that dogged her off and on almost to the end of her days. Flagstad was no saint. She had her petty diva feuds and perhaps held some unseemly, provincial social views. What happened to Flagstad, however, wasn’t karmic revenge but diplomatic sadism. Under these conditions (sometimes better, sometimes worse) she sang her electrifying La Scala Ring cycle under Wilhelm Furtwängler, made her classic recording of Tristan und Isolde and premiered Strauss’s Four Last Songs. As late as 1959, when all was supposedly forgiven, Flagstad’s relationship with King Olav at the Norwegian National Opera opening was frosty at best.

In these sections of the book, the reportage goes into high gear, quoting from Flagstad’s diaries as well as top-secret diplomatic memos and telegrams. It’s a staggering achievement, helped partly by Solbrekken’s having written two previous Flagstad books and being an expert in Second World War Norwegian history, as well as being a playwright. The author is laudably transparent when hitting informational blank spots. Her sharply detailed passages of historic context stop short of claiming to know what people were thinking. But the crucial question of why Flagstad stuck by her husband (and made her near-fatal 1941 return to Norway) is given a far-reaching, comparative treatment with a case history of the unconditional devotion that Winifred Wagner at Bayreuth had for Adolf Hitler. Flagstad’s husband was morally far above that, but we understand that loyalty can be maintained through highly selective perception of powerful male personalities. Political views tend to be perceived in black and white. Most often, however, such views are highly nuanced and dictated by a social context that’s not fully understood in retrospect. Who’s to judge?