When considering why so much urban and contemporary art exists in today’s Berlin, it is important to acknowledge the abundance of ambiguously owned and minimally policed property that was available during the early post-Wall era, as well as the accrued cultural capital the resulting works have offered to local government and developers in the last two decades, but the story of graffiti culture in Berlin begins as early as the 1970s, says Berlin culture expert Lutz Henke.

He explains: “On 21 July, 1971, The New York Times published an article titled ‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals, highlighting how the graffiti writing subculture had suddenly exploded when everybody thought it was dead already. And then you had the war against graffiti. There were films, like West Side Story and also Style Wars, and then Wild Style, and in 1984 all of this suddenly arrived in West Berlin. You had these somehow-invented four elements of hip hop, and you had some kind of break dance and graffiti subculture, and almost nothing of that in the east of the city. And there was this huge wall, so people painted it from the west side. It created some kind of tradition of painting property that was not yours.” He adds, “The Berlin Wall belonged to the east side of the city, to the GDR, so you also wouldn’t expect to be jailed for painting it.”

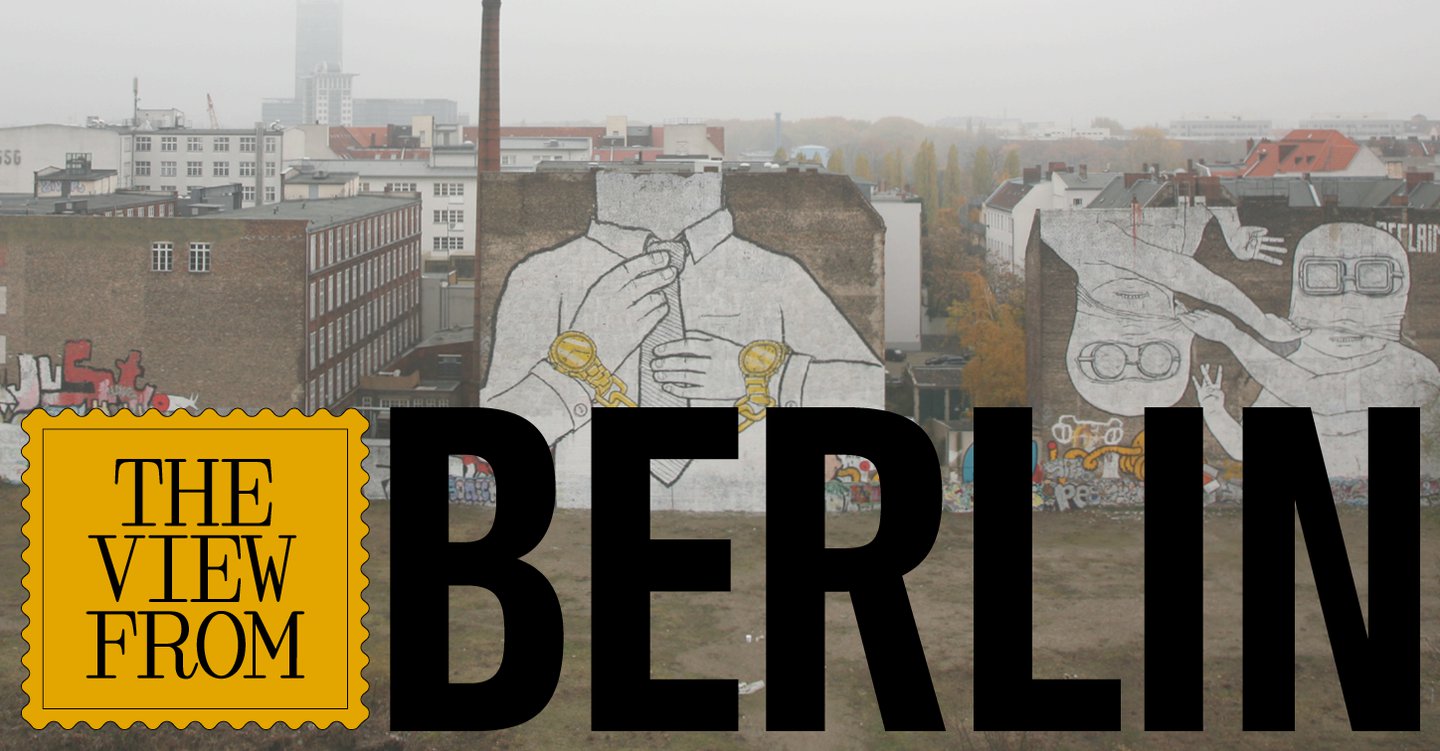

Today, Lutz is director of culture for Berlin’s official tourism organisation VisitBerlin, but his career in urban art and culture began on the streets of Berlin, the city that raised him. He is a co-creator of two infamous murals by Italian artist Blu, which were located in the Kreuzberg district of the city before being controversially painted over by Blu and Lutz themselves, as a protest against the gentrification of the neighbourhood.