There’s been only one topic of conversation in the brasseries of France this week: Prime Minister Francois Bayrou’s proposal to scrap two of three public holidays in the month of May to contain the spiraling budget deficit. In the land of the 35-hour work week, this is tantamount to treason. Most of the public seems to hate it, unions have called it a declaration of war and the far right has called it a provocation.

The outrage is a little overdone. Knocking off two public holidays would leave the French with nine, which looks positively Germanic — until you add their 25 paid vacation days, which gets France in almost the same ballpark as Spain. (And no need to mention the extra days that many private-sector workers get for working more than 35 hours.) And while there’s been plenty of gnashing of teeth at Bayrou’s description of the month of May as “gruyere” cheese — full of holes — it’s kind of true. France is a place where the calendar is a Sudoku puzzle to find the ideal combo of holidays and vacation; this year, it’s been possible to strategically place five days’ vacation and get 32 days off.

Bloomberg

Bloomberg

But even if this idea somehow survives the political backlash, there are two problems with it. One is that in terms of getting the French economy out of the doldrums, it’s small beer. It would theoretically add about €4.2 billion ($4.9 billion) to the public purse, which works out to about 10% of the savings the government is looking for next year. The other is that it amounts to working more for less, instead of the “work more to earn more” philosophy promoted by President Emmanuel Macron when he was first elected. Workers would get no extra pay for the month while at the same time being exposed to other belt-tightening measures the government has in store. It’s a stopgap, not a structural reform.

And structural reforms are what France needs to keep its social model from running out of road. While it’s wrong to say that France is the new Greece, it has among the highest debt and deficit ratios in the euro area and among the lowest growth rates (though ahead of Germany). Its “open-bar” economy is under long-term pressure from demographic decline and weak productivity. And while recent reforms have gone in the right direction, even Macron has reverted to type by spending big in a crisis but failing to cut back when the storm subsides. That makes it harder in the long term to invest in the skills, technology and infrastructure that are critical to boosting prosperity in the long run.

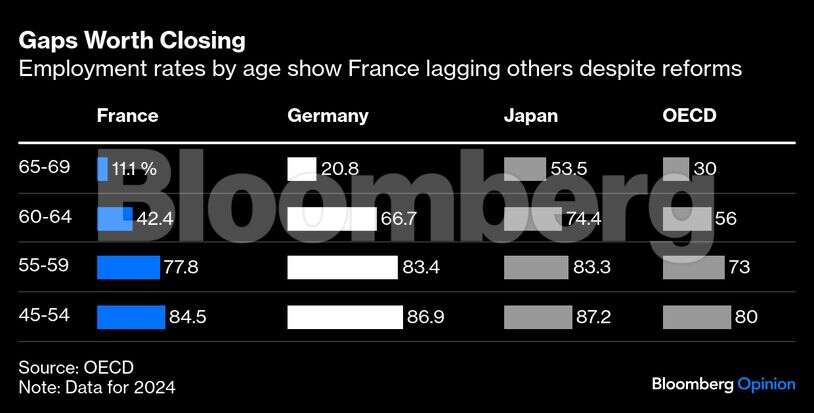

Instead of adopting the language of a household living beyond its means, which will only aggravate parliamentary bust-ups over soaking the rich and shrinking the state, the Macron administration should talk more about valuable resources that remain untapped. These include getting more people into work, not shaking an extra two days out of those already in it. OECD data suggests that France’s overall employment rate of 69% is still below average — closing the gap could add as much as 10% to output, according to Natixis SA economist Patrick Artus. More jobs for older workers, getting more women into work and a smart approach to immigration would help growth, offset the demographic challenge of the boomer retirement wave and reduce the pressure on public finances. The tax burden on workers already saps firms’ ability to raise wages.

This obviously won’t suddenly defuse the mud-slinging in a divided society. Nor will it suddenly create a productivity miracle, unless artificial-intelligence startups like Mistral suddenly deliver a breakthrough. But if the aim is preserving a French and European way of life at a time of slowing growth, there are better ways to get there than re-slicing the public-holiday gruyere.