Ever since they pinballed out of the Welsh valleys and into the ravenous pages of the music press at the start of the 1990s, Manic Street Preachers have given good copy. A riot of cheekbones, eyeliner and furious provocation, they began their career by promising to set fire to themselves on Top of the Pops, insisted that their on-stage posturing wasn’t rock cliché but “a geometry of contempt”, and vowed to release one multimillion-selling album, then split up.

It didn’t quite work out like that. In February, almost exactly 30 years after the harrowing disappearance of their ideological and aesthetic powerhouse Richey Edwards (who was legally declared dead in 2008 and is widely presumed to have taken his own life), the Manics released their 15th album, Critical Thinking. It is the latest offering from a band who have forged onwards into a creative middle age against the harshest of odds.

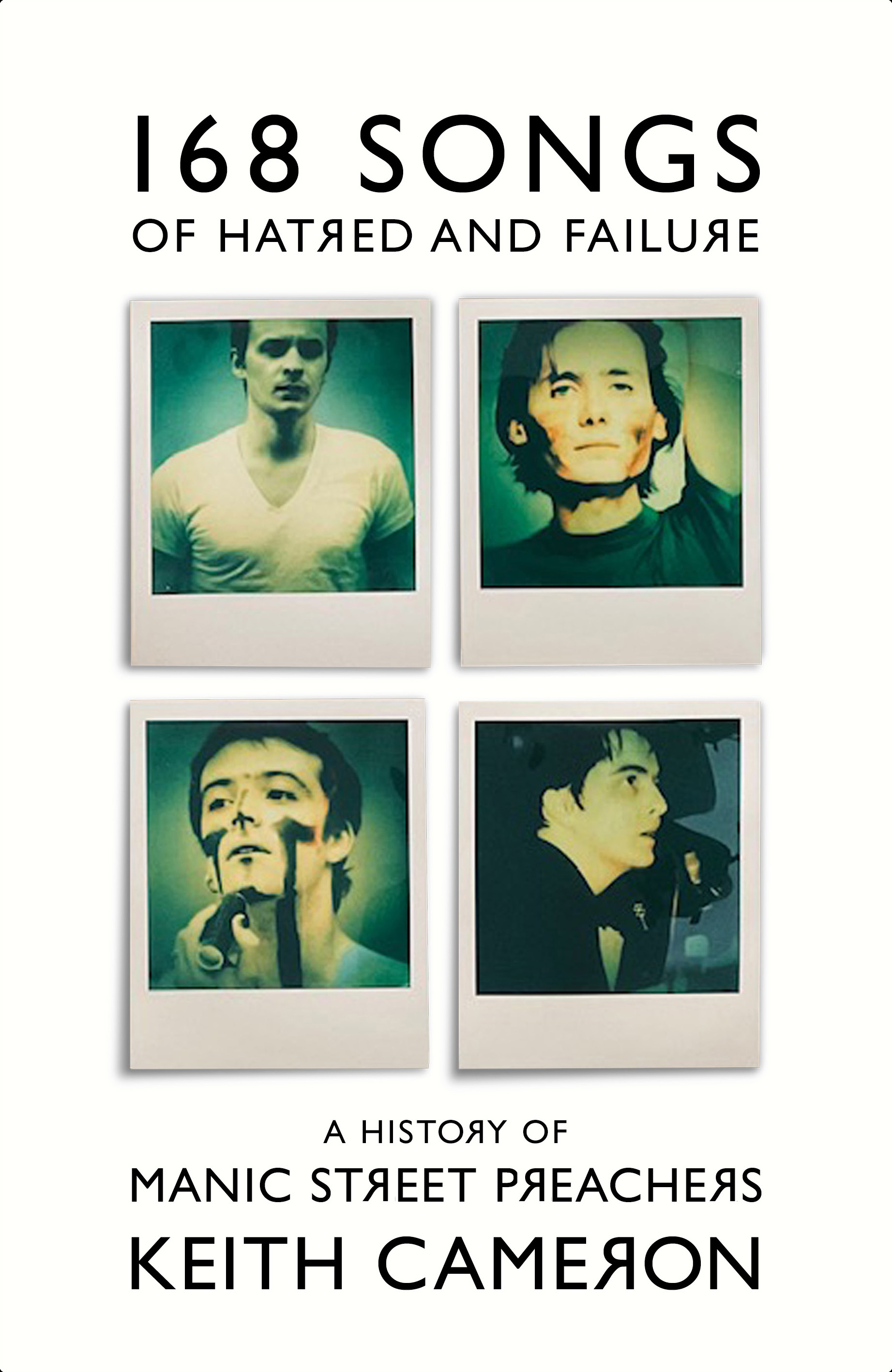

With 168 Songs of Hatred and Failure, the music writer Keith Cameron expertly tracks that trajectory in all its glory and tragedy, his song-by-song approach allowing for the exhilarating close reading demanded by a band as likely to throw in an allusion to Valerie Solanas or Guy Debord as Penderecki or Public Enemy. Whittled down from 319 extant Manics songs — not 168, which refers to the number of seconds their 1991 single Motown Junk suggests is the perfect length for a pop song — the book’s carefully curated selection allows for a fascinating analysis of this wildly idiosyncratic band, one that catches as much of their complicated spirit as it does their turbulent history.

• James Dean Bradfield: ‘I stopped drinking so there’s no partying’

Cameron met the Manics in 1994, having previously defended them against Rick Wakeman on the BBC talk show Kilroy when the incendiary sloganeering of their song Repeat (“repeat after me/ f*** Queen and country”) caused a froth of outrage. His bond with the band has endured and this book is enriched by new interviews with the Manics’ singer James Dean Bradfield and bassist Nicky Wire, their commentary astute, affecting and often balefully funny.

There are revelatory insights into the band’s original dynamic — Wire and Edwards working as the lyricists, Bradfield and the drummer Sean Moore the musical wing — with Bradfield displaying a grace and commitment that’s incredibly moving. He might not always have agreed with the words he was given, he says — as with the intense interrogation of language and politics in the song PCP — but “sometimes it’s nice doing that on behalf of somebody … I just loved being among its flow.”

Wire, meanwhile, offers a trenchant description of their worrying lack of chart traction after the release of From Despair to Where, the first single from their second album, Gold Against the Soul (1993). “A lot of bands would have buckled at that point. But we kept digging. We dug so far we reached hell.”

This is heaven for Manics fans, but even those readers without any spray-painted white denim lurking in their wardrobe will find it hard to deny the power of the story that unfolds through Cameron’s rich analysis. The early songs are a reminder of what Clash-y, trashy outliers the band were when they first appeared, Edwards and Wire in particular being thrown into interviews like unpinned grenades.

If you want a clear example of their shift from rouged rogue element to respected elder statesmen, just look at Bradfield’s present attitude to the line “I laughed when Lennon got shot” in Motown Junk. “We came out trying to prove too many things to too many people too quickly. I don’t even like thinking about that line.”

It was The Holy Bible in 1994 that fundamentally shifted attitudes to the band. Its carbonised, charcoal-black despair was suggestive of Edwards’s escalating issues with self-harm, anorexia and alcohol. The Intense Humming of Evil and Mausoleum emerged after visits the band made to Belsen, Dachau and Hiroshima; 4st 7lb described an anorexic girl’s desire to “walk in the snow and not leave a footprint”.

Wire recalls Edwards handing him the lyrics of Archives of Pain — a song about the death penalty inspired by Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish — with a smile and the words: “I think you’ll like this.” This was at a time, Cameron reminds us, when Britpop’s “cultural knotweed” was spreading. “Don’t forget,” Wire says, “our contemporaries were talking about cigarettes, alcohol and going to Greece for a holiday.”

Part of this superb book’s strength, however, lies in its commitment to telling the story of the band after Edwards’s disappearance. Cameron describes the “bittersweet miracle” of their comeback with A Design for Life, a single that reclaimed the power of their Welsh working-class roots from Britpop’s ironic flat-cap appropriations. “Greyhound racing!” Wire says, possibly thinking of Blur’s artwork for Parklife. “I’ve been greyhound racing, at f***ing Bedwellty, and it’s shit.”

Richey Edwards in the offices of the NME in 1992

MARTYN GOODACRE/GETTY IMAGES

Within five years, they had written two million-selling albums — Everything Must Go (1996) and This Is My Truth, Tell Me Yours (1998). Later songs — Journal for Plague Lovers, for example, from one of the batch of lyrics Edwards left with the band, or the 2025 bonus track Johatsu — are treated with the same care as the banner glam and marquee gloom of their imperial phase, deepening the Manics’ continuing story.

• Manic Street Preachers: ‘We were waiting for Richey Edwards to come back’

The success of a music book is often measured by how quickly it sends the reader back to the records; 168 Songs of Hatred and Failure does that — very fruitfully too — but Cameron writes so vividly and precisely it’s almost unnecessary to rush to the albums. The joy is reading about the “brawny, fissile” guitars of Motown Junk; the effect of the miners’ strike on the band’s collective political consciousness; and the shades of The Producers’ Springtime for Hitler Cameron detects on Revol (“Mr Stalin — bisexual epoch/ Khrushchev — self-love in his mirrors”).

“For us, music and words came first, and everything else was secondary,” Edwards says in the book’s epigraph. 168 Songs of Hatred and Failure is further brilliant testament to how the two can work together.

168 Songs of Hatred and Failure: A History of Manic Street Preachers by Keith Cameron (White Rabbit £30 pp560). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members