Peyrin Kao, a lecturer in UC Berkeley’s Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, or EECS, department, was suspended by campus for the spring 2026 semester on the grounds that he used the classroom to “advocate for political views concerning topics that (are) not germane to (Computer Science 61B),” the computer science class he teaches on data structures.

The political views he expressed and for which he was found in violation of UC policies did not concern the problem of climate change, the rising costs of health care, ICE raids or the war in Ukraine, for the expression of political views on these issues in the classroom would not have led to an investigation, let alone a suspension.

Instead, he spoke about Israel’s genocide in Gaza, an ongoing event that he felt morally compelled to oppose given his position as an instructor in a department and participant in an industry that both have strong links to the Israeli war machine.

Over the last few days, the Berkeley Faculty Association and the Berkeley Initiative for Freedom of Inquiry have both come out with letters strongly objecting to Kao’s suspension, highlighting the questionable interpretations of University policy found in Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Benjamin Hermalin’s statement of finding on the case.

Framing the issue in terms of academic freedom and protected speech, both letters cite Kao’s clear efforts to abide by UC systemwide policies on political speech in the classroom. The letters also say that Hermalin’s statement twists the letter and spirit of the policies he cites in order to impugn Kao’s behavior. I applaud these responses to this latest move by the UC system to further limit free speech on campus.

However, in framing Kao’s case solely as a matter of free speech, we leave out two of the most important contexts that bear on its assessment.

The first is the genocide itself, including the imposed starvation of Palestinians that continues today with full U.S. support. The second lies in the current refashioning of the U.S. educational system as a whole — enacted under pressure from the federal government and with the compliance of university administrators — to ensure loyalty to and support for Israel and its genocidal policies.

Just last week, nine lawyers formerly employed by the Department of Justice reported that they had been pressured by their bosses to provide support for a charge of widespread antisemitism across UC campuses even before they had begun their investigation — a tactic meant to give further leverage to President Donald Trump’s administration in its aim to bring universities to heel.

Importantly, these and similar efforts by Trump and former President Joe Biden to silence criticism of Israel on campus are only one piece of a broader project aimed at deepening the alignment of U.S. political, military, technological and educational institutions and industries with Israel. Recent reports on the extensive role of American technology firms in supporting Israel’s war-making capacity testify to this growing economic and technological interdependence between the U.S. and Israel.

UC administrators’ suspension and silencing of Kao must be seen as one action within this broader project binding American and Israeli societies together — a project that U.S. universities have widely embraced but one that Kao has rejected.

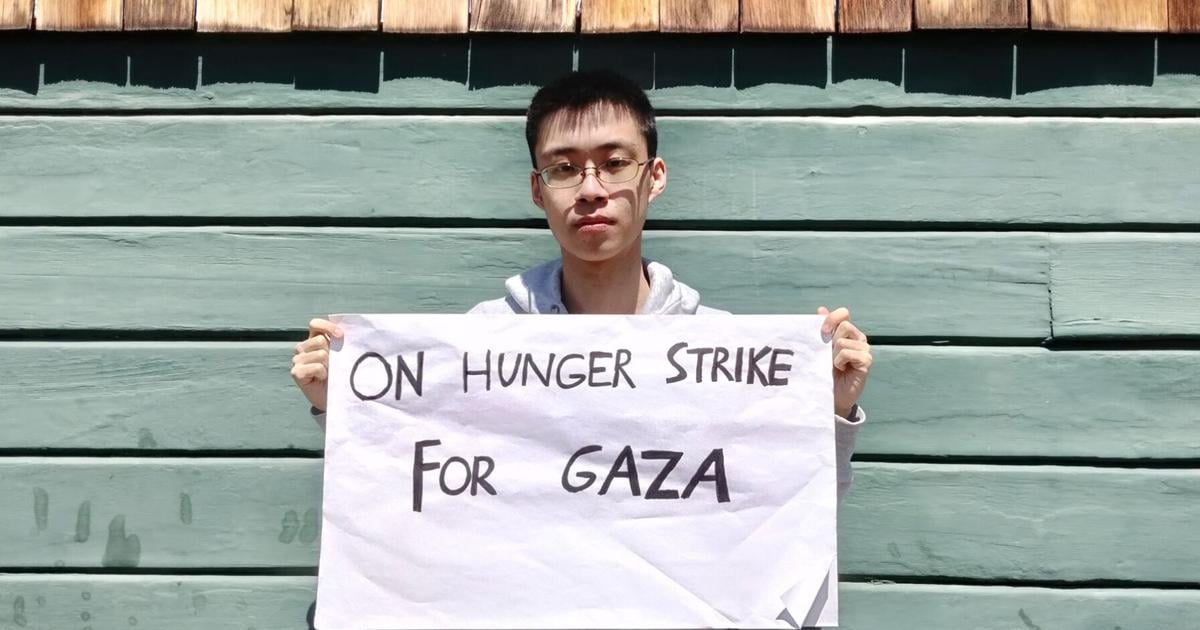

In an interview with the online news site “The New Arab,” Kao explained his decision to go on a hunger strike referencing both the genocide in Gaza and the U.S.’s complicity in this act. The lines of the interview cited in Hermalin’s finding read, “With this hunger strike, I hope to bring the starvation here, to Berkeley, in front of my students, to remind them that the Palestinians being starved by Israel are just as human as we are … But in my view, it’s crucial that students studying computer science or other tech-related subjects think critically about their roles in industry after graduating to make sure they are contributing to solutions to the world’s problems, and not becoming cogs in the war machine.”

Kao thinks students should know that Palestinians are being starved by Israel — that this knowledge is important for them to think critically, particularly as they will be entering a field that is implicated in the genocide. The decisions they make, he suggests, may well have a direct impact on this and future genocides.

Kao does not want his students to be part of this war machine and feels responsible to ensure they have the knowledge they need to navigate such a difficult moral terrain. He recognizes that the field of computer science, given the immense power it has in shaping our collective future, requires an awareness of the world that goes beyond math and coding skills.

He knows, and has been told by his department chairs, that speaking about this during class time is forbidden, so he seeks out other ways to pass along this crucial knowledge to his students, in the moments after his lectures and through the visibility of his hunger strike.

However, Hermalin takes Kao’s words from outside lecture as evidence that he “intended to influence his students’ thinking on political matters,” that he brought a non-course-germane topic to the classroom with the aim of political advocacy. He disagrees with Kao’s view that knowledge of the genocide in Gaza is crucial to the preparation of future programmers and engineers.

As a trained practitioner in computer science and therefore someone better positioned to judge the needs of his students — unlike Hermalin — rejects this position. The moral calamity of the genocide in Gaza, Kao suggests, cannot be circumscribed to classes on Middle East politics and history; its import crosses disciplines, including computer science.

Kao is not alone in this view. Workers at Google and Microsoft have also sharply criticized their companies’ involvement in the Israeli onslaught on Gaza and have been consequently laid off. They also perhaps imagined that their career choice would enable them to solve the world’s problems, not feed the war machine.

In suspending Peyrin Kao, UC Berkeley has not simply violated an instructor’s freedom of political expression. It has shown itself to be a willing proponent of the brave new world for which the genocide in Gaza stands as testament and warning.