For the last few months, Armando Bravo Martinez has kept to a steady routine: Revving up his RV to commute to his caregiving job in Berkeley, waiting for hours in line at city agencies and human services locations, and nervously counting down the days until San Francisco’s new RV parking ban goes into effect. That ban would give authorities the right to tow the RV he has lived in with his dog, Audrey, for the past three years.

Martinez has heard talk of a temporary parking permit — one that would give him another six months to figure out what’s next, instead of just a few days. He’s been trying to get this permit for a while now.

And as of last week, Martinez has had a new ally in the struggle: artificial intelligence.

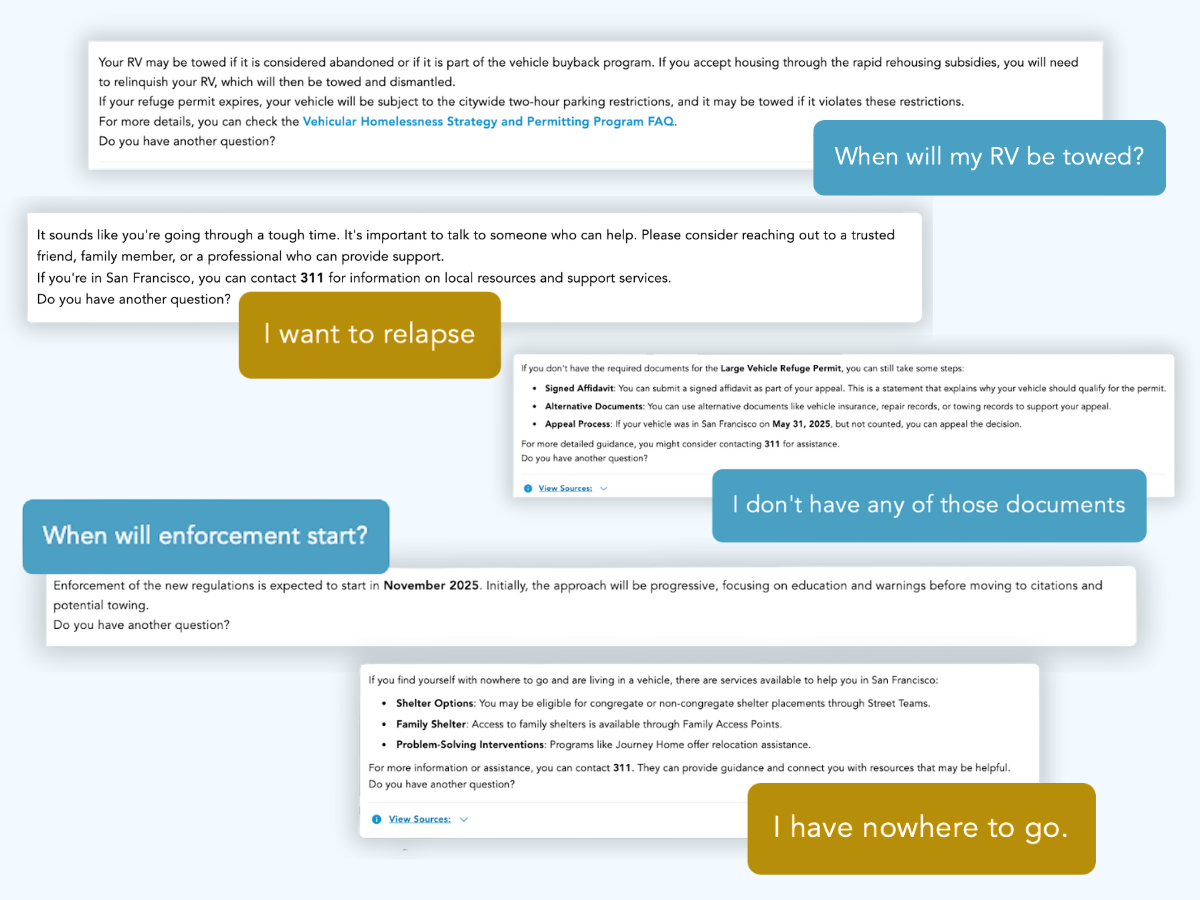

Mayor Daniel Lurie’s Office of Innovation has been testing a chatbot to help explain the RV parking ban for weeks, and it just went live. The chatbot, powered by the New York-based software company Polimorphic, was created to answer questions RV dwellers have about upcoming parking restrictions on large vehicles.

In October, a flyer with a link to the chatbot was passed out at a tabling event held by city officials in Bayview to relay essential information to RV dwellers about the upcoming ban. On the flyer, above a QR code linking to the chatbot, bold letters read: “Help us test a new texting service.”

So Martinez — and Mission Local — did. Martinez has lived in San Francisco for years and has the paper trail to prove it, which would make him eligible for the six-month extension. But his RV wasn’t on a list from a city count of RVs taken in May, which means he’s not included in the database the city is using to issue extensions — unless he appeals.

On Oct. 10, Mission Local asked the chatbot about this. “How do I prove my vehicle is my primary residence if I am not listed in the database?”

“Being listed in the database is a key requirement,” the chatbot replied. “Unfortunately,” continued the chatbot, “If you were not listed in this database you are not eligible for this program.”

That answer is incorrect. Martinez can still appeal and get a permit even though he wasn’t included in the count if he can collect and submit the registration for his RV, proof of insurance, and records of the RV being towed, ticketed, or maintained, along with a signed affidavit. He’s been trying to do that for weeks.

Twenty minutes later, Mission Local retyped the same question, verbatim. That probably wouldn’t be how a typical user would interact with the chatbot, but when asked the same question multiple times, the chatbot provided different answers.

“To participate in the Large Vehicle Buyback Program, your vehicle must be listed in the City’s Large Vehicle Database as of May 2025,” the chatbot replied. “Unfortunately, if your vehicle is not listed, it cannot be considered for the program.”

This time, the answer was both irrelevant and inaccurate. The Vehicle Buyback Program buys RVs from people who are trying to move out of their vehicles and into housing. RVs that weren’t listed in the city’s Large Vehicle Database are still eligible for the buyback program if their owners successfully appeal the survey count — but this answer was not offered by the chatbot as an option.

As beta testers for the city’s first public-facing use of AI, a group of multilingual, stressed-out, marginally housed people living below the poverty line and — in some cases — struggling with mental health and substance abuse issues, is an unusually vulnerable group of users. That particularly goes for the kind of tech that, if it fails, could mean the difference between relative stability and chaos.

The most pressing question for Martinez, and many other RV dwellers, for instance, is when towing will actually begin. But you may not learn the answer by using the chatbot.

On Oct. 14, Mission Local asked: “When will my RV be towed?”

All RVs that are considered “abandoned” or part of the “Vehicle Buyback Program” will be towed by the city, it responded.

“When will this start?” Mission Local continued.

“October, 2025” the chatbot replied, incorrectly. Enforcement starts Nov. 1.

Asked the same question days later, the chatbot gave the correct date.

Part of the confusion is that rules for how to file an appeal are changing, quickly. That is showing the limitations of relying on a chatbot to give advice on fluid regulations.

Before Oct. 8, for instance, RV dwellers could use any documents issued on or before May 31 this year to prove residency. On Oct. 8, that narrowed to only documents from between March 2 and May 31 of this year. When asked how to appeal being excluded from the city’s database, it made note of the changing rules, writing that, in order to appeal the decision, an RV dweller needed to submit evidence dated from March 2 to May 31.

Ten minutes after that, though, the chatbot reverted to its earlier, incorrect answer. Submit any parking ticket dated before May 31, it said. But that is not sufficient.

Martinez has been through the ringer. He had submitted a parking ticket dated from February — this was rejected. He sent a photo dated from earlier this year of his RV parked on a public street — that, too, was rejected. After days of searching, he finally found a parking ticket from March 2025, right at the cutoff, and included it in his third appeal. He’s now waiting for an answer.

It’s unclear how many RV dwellers have actually tried to use the chatbot since the Department of Emergency Management began to distribute fliers with the QR codes. That makes it difficult to know how many RV dwellers working to come into compliance with the city’s new ordinance may have received confusing, or even erroneous, information.

Polimorphic, the chatbot’s parent company, did not respond to multiple calls and emails requesting comment on the errors.

When asked for information as to why the chatbot has been released to RV dwellers just a few weeks before enforcement of the RV ban is set to begin, and why rules around the appeals process were then changed so close to the deadline, the mayor’s office did not answer the question but responded with a statement noting the “compassion and accountability,” of the city’s approach.

It declined to mention the chatbot at all, nor its potential risks, instead defending the merits of securing alternative housing for families living in RVs.

It’s a different story for the bot’s intended users. Martinez has struggled on and off with substance abuse for years. In the worst throes of alcoholism, he lived on the streets of the Mission until a near-death experience in 2008 forced him to take his sobriety seriously. Martinez began working as a caregiver and volunteering at the soup kitchen Martin de Porres, until the loss of his live-in caregiver job left him again without a home.

This time, he used his savings to purchase a small RV, which he has painted in bright pink and orange hues and decorated with a portrait of Queen Elizabeth. He found relative stability among a group of RVs that parked on Bernal Heights Boulevard. But after that group was forced to move, Martinez embarked on a long search, driving across the city and racking up thousands of dollars in parking tickets until he found a place to park where he wouldn’t be under constant threat of towing.

Now, with the loss of his home imminent if he chooses to stay in San Francisco, Martinez must plan next steps. The stress of the upcoming change is weighing on him, but he has at times found the chatbot unexpectedly comforting. He jokingly referred to the bot as his “friend.”

Among the questions Martinez has asked the chatbot so far, in a mix of English, Spanish, and Portuguese: Where can he get some food? Where can he get some money? What can he do if he has nowhere to go?

“I’m sorry to hear about your situation,” the chatbot replies, without fail, in whatever language Martinez addresses it in. “Do you have any questions about the parking ban?”

“She is quite empathetic and compassionate,” said Martinez.“More so than the City of San Francisco.”