Rudy Batka was tired of sleeping on the streets. He was tired of drugs ravaging his body. His daughter had grown up without him — she had become a mother, with a 3-year-old son whom Rudy had never met. Rudy’s own mother, Mildred, was dying. And his wife was looking for a divorce.

For five years, he had slept on the streets of San Francisco, addicted to fentanyl, as his former life in Weeki Wachee, Florida, went on without him. But in early July, he had a moment of clarity. He stumbled into one of San Francisco’s homeless “access points,” hoping to find a case manager who could help him return to Florida, where an empty trailer in his mother’s backyard awaited him.

Inside the access point, a small office in the SoMa neighborhood, posters with information about resources for homeless people filled the walls. A woman came from behind a cubicle to greet Rudy and typed his name and Social Security number into a computer.

Rudy had taken an assessment with the city in May, the woman’s records showed. The city uses a points-based ranking system to prioritize aid for homeless people, and his score was nine points shy of qualifying him for housing. He had failed his homelessness exam.

The woman explained that there was nothing else she could offer, though there is a policy in place that requires social workers to refer homeless people to relocation services. She told him to retake the assessment in three months. Maybe then, he would be despairing enough for the city to help.

“This is why I don’t do this,” Rudy said, as he limped from the building. That night he slept in a park.

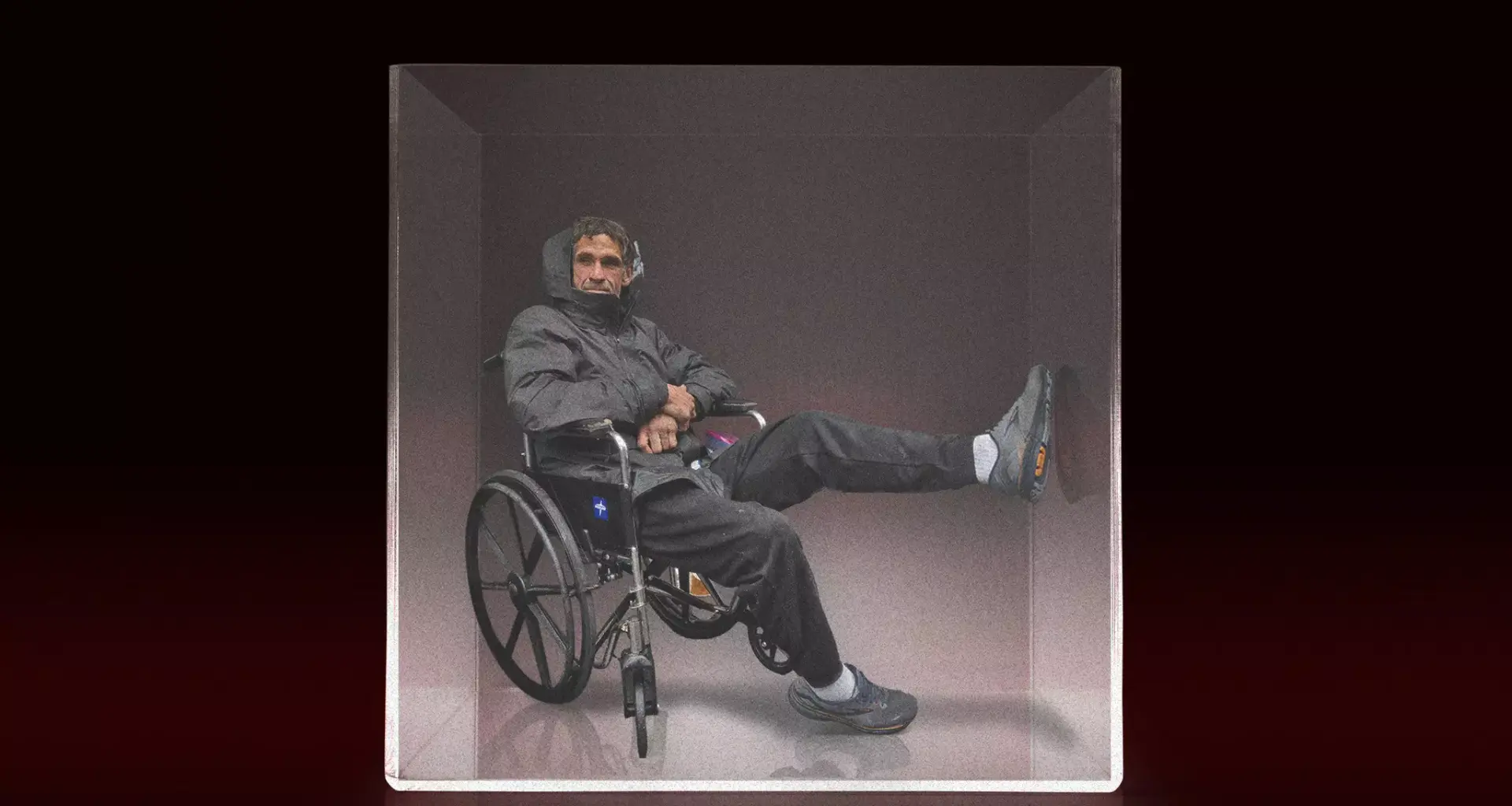

Rudy Batka, 45, rides a bus to the social security office in San Francisco on Monday, July 14, 2025.

Rudy Batka, 45, rides a bus to the social security office in San Francisco on Monday, July 14, 2025.

Since 2020, San Francisco has allocated more than$3 billion to its homelessness response, maintaining and expanding its stock of what now totals more than 14,600 units that can house more than 19,300 people, along with 3,800 shelter slots. But the need far outstrips the housing available, necessitating a system to prioritize people based on how desperate they are.

In that process, thousands of homeless people who don’t clear the bar for subsidized housing are left in an ill-defined category the city calls “Problem Solving,” in which they are supposed to receive financial assistance or other aid that helps them get off the street.

But for Rudy and the vast majority of other people in this category of social services, Problem Solving doesn’t solve their problems. Rather, they languish in a status of homeless “purgatory,” as one critic called it. They are assessed and reassessed for years, until one day they may be considered hopeless enough to receive housing — if that day ever comes. San Francisco’s own coordinated entry materials (opens in new tab) feature a flow chart that shows Problem Solving as a potentially endless loop.

Cities across California must do this difficult math every day, sorting a limited amount of resources among too many people who need them. Each city defines a successful outcome differently, and each reports wide variations in that success. In Sacramento, 34% of people referred to the category achieved a positive outcome, according to data obtained by The Standard. In L.A., 15% of households saw a successful result.

‘It’s one of the most important questions we’re facing right now. Every day somebody is on the street they’re going to see a degradation in their physical and mental health.’

Sharky Laguana, member of the SF’s Homelessness Oversight Commission

In San Francisco, a 2022 evaluation (opens in new tab) found that just 8% of people who were referred to Problem Solving received any services from it.

In theory, Rudy may have been the perfect candidate for Problem Solving’s programs. He didn’t necessarily want housing; he just wanted help. But whether because of systemic shortcomings, the complexity of his condition, or both, he continues to fall through the cracks.

“They run you in circles over and over,” Rudy said. “I’m just so tired of getting nowhere.”

The homelessness exam

The homelessness exam

Seventeen questions determine who receives a home in San Francisco and who doesn’t.

It’s considered the “front door” of the homeless response system. The federally mandated “coordinated entry process” attempts to fairly triage the city’s housing resources to those who need them most.

Homeless people can take the exam every six months, answering questions intended to assess their vulnerability. Most don’t know how the questions are weighted. But theoretically, anyone with the answers to the test, which was obtained by The Standard through a public records request, could game the system.

The questionnaire is designed to prioritize people who are unlikely to survive much longer without housing. Disabling conditions, such as drug addiction or mental illness, as well as longer stints of homelessness, increase the likelihood of receiving housing. So does getting arrested. Whether a person is originally from San Francisco is not considered.

The score needed to land on the housing waitlist fluctuates depending on the availability of beds. Rudy’s score was 114 in May, when the threshold was 123.

Rudy on his wedding day. | Source: J.P. Batka

Rudy on his wedding day. | Source: J.P. Batka Rudy with his mother and brother. | Source: J.P. Batka

Rudy with his mother and brother. | Source: J.P. Batka Rudy and his brother. | Source: J.P. Batka

Rudy and his brother. | Source: J.P. Batka

Although thousands of people may be in Problem Solving status at any given time, most do not make it into a Problem Solving program. Instead, the status merely serves as an indicator that the person hasn’t achieved a score high enough for housing.

Explanations for Problem Solving’s poor performance vary. Some say it’s underused. Others argue that the program is fundamentally flawed since it attempts to resolve homelessness without providing housing. City officials say it was never meant to be a broad solution but rather a narrow intervention for people whose homelessness could be resolved quickly and cheaply.

“Problem Solving was never intended to end the majority of homelessness,” the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing said in a statement. “But rather to work on the margins to divert people out of the system quickly.”

For people on the brink of homelessness and who need a quick infusion of cash to stay off the streets, Problem Solving is the most cost-effective solution. At an average $2,023 a household, the city housed 215 individuals and families in problem solving between July and October 2025. But that represents only 4% of the 4,861 households placed in Problem Solving status during that time.

For almost everyone else, the category is a waitlist to nowhere. Social workers say the status is a “black hole,” and its programs lack the capacity to resolve homelessness. On the streets, its reach appears even thinner: Many unhoused residents told The Standard they had never heard of Problem Solving at all.

With federal housing dollars under strain, urgency grows for answers on how to free the thousands of people stuck in this limbo.

“It’s one of the most important questions we’re facing right now,” said Sharky Laguana, a member of the city’s Homelessness Oversight Commission. “Every day somebody is on the street they’re going to see a degradation in their physical and mental health.”

‘Stay with me, Rudy’

‘Stay with me, Rudy’

Rudy struggled to walk from the homeless access point in SoMa this summer, sleep-deprived and consumed by pain. Earlier that week, he had received an injection of a withdrawal medication that made him sick. Its effects were dwindling, which meant he was starting to feel better. But he was running out of time before his fentanyl cravings returned.

To Rudy’s knowledge, he had no case manager. His interactions with outreach workers were always fleeting, and he was too ashamed to return to the sobering center he had left days earlier.

The causes of homelessness in the city are complex and varied. In the most recent point-in-time survey, job loss was the most commonly cited trigger, mentioned by 22% of respondents. Another 18% attributed their homelessness to drug or alcohol use, and 14% said they had been evicted. In dozens of interviews with The Standard, people attributed their homelessness to some combination of these factors.

Rudy’s path to the streets was similar. He moved to Sacramento in 2015, where he worked for two years before suffering a severe injury to his hip, he said. Unable to walk, he lost his job, was evicted from his apartment, and moved to San Francisco in need of housing or financial aid. Instead, he found fentanyl.

Like roughly half of unhoused San Franciscans, Rudy’s homelessness is entangled with his addiction, each condition compounding the other. The instability of sleeping on the streets makes kicking the habit that much more difficult, and the addiction puts housing out of reach. He often fails to follow through with appointments for treatment or financial aid, and most — if not all — of his money goes toward his drug habit.

There was a health clinic down the street from the access point that was known for treating drug users. But he was wary of it. The three long city blocks seemed too daunting, the possibility of being turned away too high. But after confirming that treatment was available, he obliged.

At the front desk, a man in dark sunglasses ushered Rudy into a waiting room. Within minutes, a nurse called him into the doctor’s office.

Rudy faded in and out of consciousness as Dr. Noelle Martinez, an addiction specialist, talked him through treatment options. She urged him to take a second dose of the withdrawal medication, which would blunt the rewarding effects of fentanyl for a month, she explained. She promised that this dose wouldn’t make him sick.

Dr. Noelle Martinez, an addiction medicine specialist with the Department of Public Health, holds Rudy Batka’s hands during a visit to the Behavioral Health Access Center.

Dr. Noelle Martinez, an addiction medicine specialist with the Department of Public Health, holds Rudy Batka’s hands during a visit to the Behavioral Health Access Center.

“It will protect you,” she pleaded, holding his hands to keep his attention. “Stay with me, Rudy. … You’re in the perfect window.”

This was Rudy’s best shot at recovery in years, it seemed. But he could hardly open his eyes or form a sentence. He was incapable of consenting to the treatment.

Martinez turned her focus to finding him a place to sleep, thinking that maybe after some rest he could make a sound decision. She called a cab to take him to a day shelter in the Mission.

By the time the shelter discharged him at 7 p.m., Rudy was rested and motivated. But the health clinic was closed, as were most other resources. Around 7:30 p.m., he disappeared into the 16th Street drug market. He promised to visit Martinez again the next morning, but he never showed. The perfect window had closed.

A policy shift

A policy shift

Few dispute that there isn’t enough housing in San Francisco. The disagreements begin over what to do about that scarcity, particularly when it comes to the persistent homeless population. Officials and advocates face off on whether it’s the city’s responsibility to provide permanently subsidized housing for anyone who needs it — and whether housing alone would solve the homelessness crisis.

California’s “housing first” policy, implemented in 2016, directs cities to use housing as the foremost response to homelessness. The approach is rooted in the idea that although homelessness is often entangled with addiction, mental health problems, and other issues, people have little chance of recovering from those conditions without a stable place to live.

To many longtime homeless advocates, the solution to helping someone like Rudy is straightforward.

“The city needs to get more serious about its investment in housing,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness. “That‘s the best way to address a guy who’s nine points shy of qualifying.”

But a new crop of leaders in San Francisco, headed by Mayor Daniel Lurie and his homelessness chief, Kunal Modi, are questioning this logic. They argue that providing a permanent place to live for every homeless person is not financially feasible.

‘A redesigned system should meet Rudy and really understand Rudy’s needs. We need a 360 view of Rudy.’

Kunal Modi, San Francisco Chief of Health and Human Services

Modi admits that Problem Solving as it stands isn’t solving enough problems. The array of government agencies tasked with helping the city’s most vulnerable residents have yet to collaborate in a way that acknowledges the complexities of people like Rudy, he says.

“Right now, depending on which front door you walk into, you’re already narrowed into a set of interventions for you. It’s not holistic,” Modi said. “It’s a hammer that sees everything as a nail, and sometimes permanent supportive housing is not actually the best outcome.”

In some of his early efforts to address these issues, Modi has positioned the Homelessness and Supportive Housing Department to focus more on addiction, opening recovery-focused shelters, advocating for sober housing options, and aligning leadership with the Public Health Department.

The idea is to create a path toward self-sustainability for people like Rudy, whose addiction poses a major obstacle to a return from society’s fringes. Modi’s next aim is to redesign the coordinated entry process to better connect people to those resources.

Rudy helps another homeless man across the street.

Rudy helps another homeless man across the street.

“A redesigned system should meet Rudy and really understand Rudy‘s needs,” Modi said. “We need a 360-degree view of Rudy.”

However, experts warn that a focus on transitional options may be ignoring the root of the homelessness problem. Rents in San Francisco, already one of the most expensive U.S. cities, are rising as evictions climb. Many homeless people don’t have a trailer in their mother’s backyard they could return to, like Rudy does. And experts caution that without continued investment in permanent housing, the city’s shelter backlogs and unending waitlists will grow.

“If someone goes into a transitional program and they complete that course, is there any evidence that they will then need something other than permanent housing?” asked Josh Bamberger, a clinical addiction specialist. “Nonmedical people like Kunal think that there’s some magic that happens when the health department gets involved that’s going to somehow change that person’s needs.”

Getting Rudy home

Getting Rudy home

Two months after Rudy left the clinic in San Francisco, his mother suffered a life-threatening infection. Believing she was about to die, Mildred yearned to speak with her youngest child.

“If I can just see him one more time,” she said in a phone call with The Standard, “then I’ll die happy.”

Within the Problem Solving framework, the city has three programs to return people to their hometowns. But the emergence of fentanyl has complicated the city’s ability to ramp up these interventions.

It’s unclear how Rudy, despite wanting to return home, would fare on a 50-hour bus ride across the country in his state of health. And if he were to arrive, it’s unlikely there would be sufficient resources for addiction treatment available to him in Weeki Wachee.

Still, in July, his brother J.P. jumped into action to fulfill his mother’s dying wish, contacting street workers in San Francisco in an effort to bring Rudy home.

Some outreach staff who had contact with Rudy said his condition had deteriorated following his visit to the health clinic, and finding him among the thousands of people on the city’s streets was a long shot. But there was hope: Rudy had expressed interest in recovery — often the most difficult step for anyone fighting an addiction.

At around 2 a.m. roughly two weeks later, an outreach worker found Rudy crumpled on the sidewalk near the corner of Sixth and Market streets. The worker called J.P., and they scheduled a doctor’s appointment for Rudy to receive a tuberculosis test, which he would need to visit his mother in the hospital.

Rudy’s family hadn’t seen him in nearly a decade, and the streets had taken their toll. He’d lost more than 40 pounds. His hair had grayed. He struggled to walk without assistance.

Defying the doctor’s prediction, Mildred was able to return home in October. But Rudy was not. He once again missed his doctor’s appointment, and the family has lost contact with him.

The opening scene of a documentary (opens in new tab) about the city’s drug crisis that was released on social media this month shows paramedics wheeling Rudy into an ambulance. Still, the Batkas hold out hope that he will one day return home. The trailer in Mildred’s backyard sits empty. J.P. says he’s ready to pick up Rudy from the airport or bus station at a moment’s notice.

But they know, as well as anybody, that Rudy’s problems aren’t easily solved.

“It would put the biggest smile on my mom’s face. I’d be the first one picking him up,” J.P. said. “But he’s got to be done with the drugs if he’s really going to come home.”