California’s wet season is off to a fast start. An early season storm delivered significant rainfall across the state this week and blanketed the Sierra with more than 20 inches of snow, a few weeks ahead of the average first snowfall date.

This has many people asking the natural question: Is this a sign of a wet winter to come?

The short answer is no. One storm, no matter how strong, can’t tell us much about what the next three months will bring. The reason comes down to the difference in time scales for weather and atmospheric phenomena.

A single October storm is driven by short-term factors that change every few days. In between those daily fluctuations and long-term trends are sub-seasonal patterns, which can shape our weather for two to six weeks at a time. By contrast, seasonal patterns such as El Niño or La Niña unfold over months, and their effects on day-to-day weather are quite variable and, frankly, not very predictable.

While a single October storm may tap into a brief alignment of moisture and jet-stream energy to produce a big storm, how subsequent months play out depends on short- and long-term factors. The 2021-22 and 2022-23 wet seasons illustrate just how disconnected those scales can be.

In late October 2021, a big storm fueled by a strong atmospheric river brought record-breaking rainfall to Northern and Central California. It gave San Francisco its wettest October day on record – 4.02 inches downtown on Oct. 24, 2021 – and set all-time daily rainfall records, including 7.83 inches in Santa Rosa, 5.44 in Sacramento and 4.89 in South Lake Tahoe. By month’s end, it ranked as the fourth-wettest October in state history.

That deluge was followed by more storms in December, building an early-season Sierra snowpack to 160% of average.

Then it all changed. Almost overnight, the stormy pattern shut down and the state went on to have two of the driest months of January and February in recorded history.

Just a year later, California flipped the script. October 2022 was exceptionally dry statewide, extending the drought that deepened through the previous winter. Then, in late December, the atmosphere reversed course. Over three weeks, nine atmospheric rivers struck in rapid succession. Between Dec. 26 and Jan.19, the state received roughly half of its average annual precipitation.

That barrage of storms extended into February and March 2023, producing one of California’s largest snowpacks on record. Southern California’s wintertime precipitation in 2022-23 was the highest in over two decades. On April 1, the northern Sierra measured 237% of average snow water content, and the central and southern ranges recorded their highest values ever.

The dramatically different outcomes of the 2021-22 and 2022-23 winter seasons were not caused by well-known cycles such as El Niño or La Niña. Instead, the answer lay in the shifting positions of the jet stream and key pressure systems.

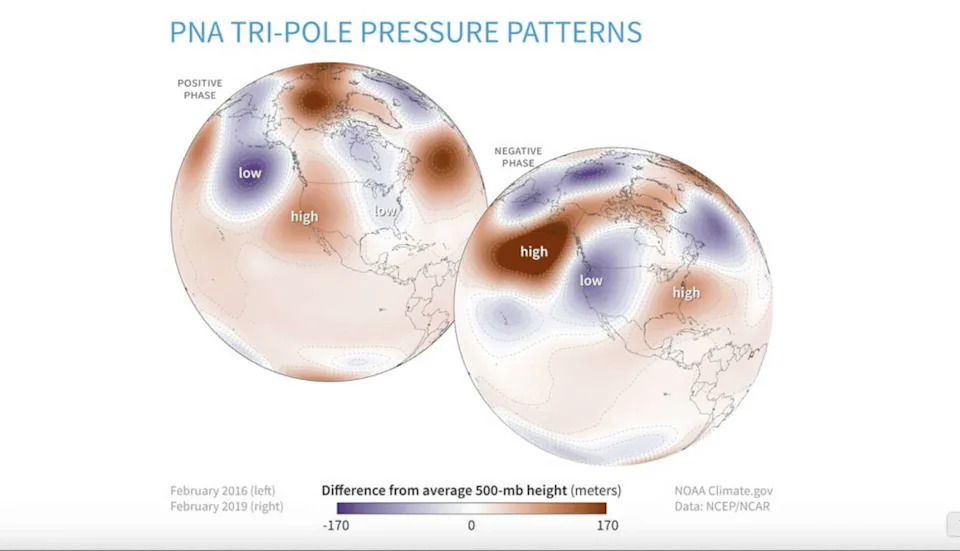

The “whiplash” of 2021-22 was a direct result of the Pacific-North American Pattern, a large-scale pressure pattern that can act like a gatekeeper for storms. The season started wet under a “negative” PNA, but flipped in January 2022 to a “positive” PNA. This change erected a strong ridge of high pressure off the West Coast, acting as a wall that deflected the storm track north and initiated a severe drought period.

The atmospheric response to a positive Pacific-North American Pattern and a negative PNA pattern. California typically sees cooler temperatures and an increase in storm activity during a negative PNA phase. (NOAA)

In contrast, the record moisture of 2022-23 was driven by the Madden-Julian Oscillation, an eastward-moving pulse of tropical rainfall that circles the globe. An active MJO entered a favorable phase for California storms in late December, altering the jet stream to funnel a barrage of atmospheric rivers into the state for weeks.

So what should we expect this rainy season?

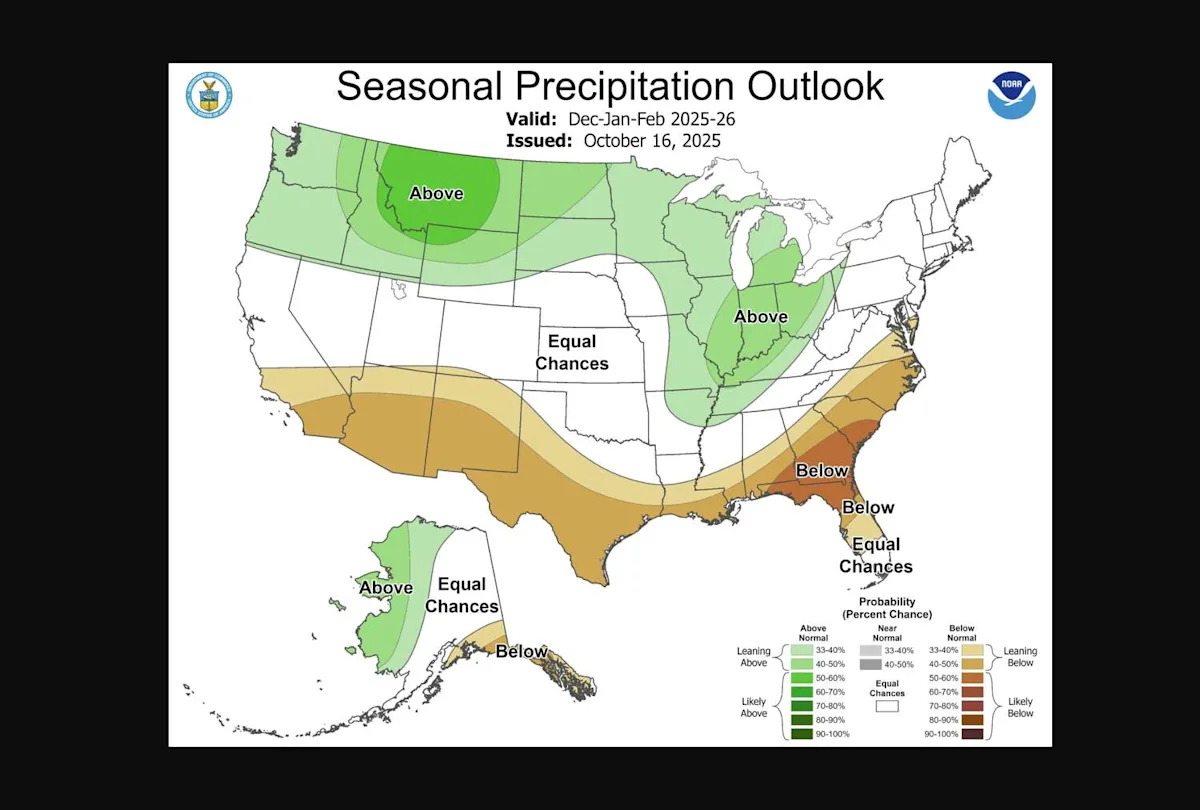

NOAA released its official winter outlook Thursday. The agency highlights the slowly developing La Niña as the primary influence on conditions for the upcoming winter across most of the country.

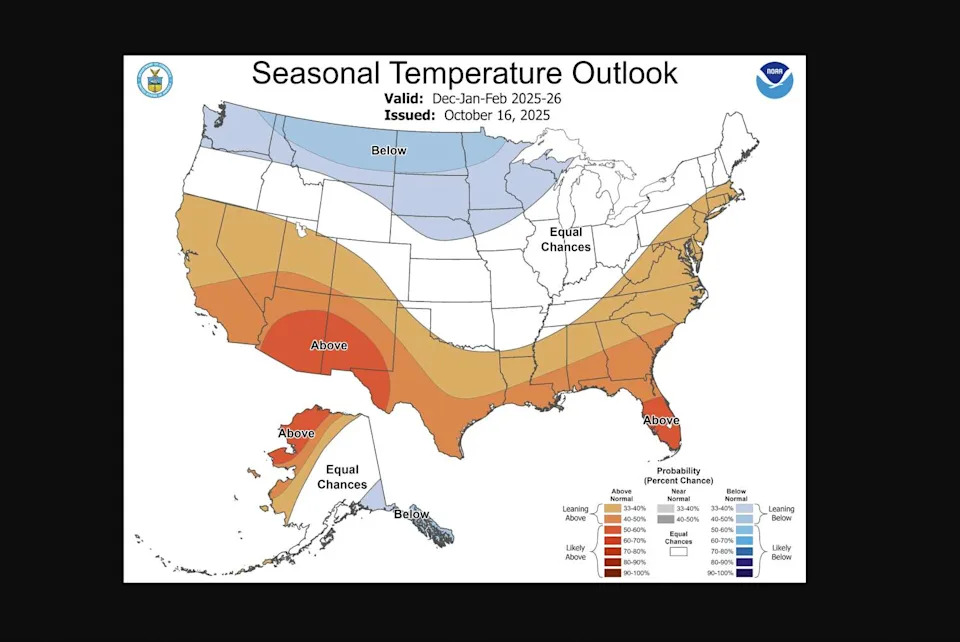

For California, that amounts to another split-personality temperature and precipitation forecast. Northern California, including the Bay Area, has a slight chance of seeing above-normal temperatures, with Southern California having a better chance at seeing above average temperatures. The precipitation outlook is more uncertain, with much of the state having an equal chance of seeing above-normal, normal or below-normal precipitation.

NOAA’s official winter temperature outlook puts much of California at a slight risk for above average temperatures, with the highest likelihood in the south east part of the state. (NOAA)

However, a major wildcard is looming in the Pacific, a perfect example of a sub-seasonal driver that could make the weather swing dramatically from week to week.

A massive area of abnormally warm water, nicknamed the “warm blob,” is lingering in the North Pacific. By heating the air above it, this warm water can shift major weather patterns, likely forcing the semipermanent Aleutian High pressure system to the south. This setup is a classic trigger for a negative PNA pattern, which typically brings a colder and stormier winter to California, even Southern California.

But the persistence of such a pattern is the great unknown. As recent history has shown, these powerful atmospheric factors can change rapidly. The “warm blob” might dominate for a month, bringing a deluge, and then break down. This potential for volatility is the primary reason the overall seasonal forecast is so uncertain.

This article originally published at California’s wet season starts strong. Here’s what that means for the winter ahead.