Time is running out! Your donation to Berkeleyside can be matched—but only until midnight on Dec. 31. Give now and double your support of our nonprofit journalism.

People lounge in the sun, spreading out blankets on Strawberry Creek Park’s main lawn, on June 7, 2025. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

People lounge in the sun, spreading out blankets on Strawberry Creek Park’s main lawn, on June 7, 2025. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Editors’ note: This week we’re republishing some of our favorite stories of 2025. This story was first published on Aug. 26.

On a foggy Wednesday morning, a group of new mothers spread out blankets, unpacked backpacks and settled in with their 3- to 4-month-old infants on the grassy meadow at Strawberry Creek Park. Once members of a Kaiser Permanente pregnancy group, the mothers have been meeting weekly in the park — the central green of West Berkeley’s Poet’s Corner.

On the large flat lawn at the park’s north end, there are plenty of shady spots for babies to sprawl and crawl and there’s the Hidden Cafe, “a place to get coffee and a snack and a bathroom, which is essential when you are here for four hours,” said Madeleine Mountain of El Cerrito. “Coffee, yeah, that is really big for tired moms.”

Parks of Berkeley

This story is part of an ongoing series exploring the history and current life of several of the city’s most notable parks.

Family friendliness is just one of the park’s attractions. By noon, the sun came out, shining a light on all of the park’s disparate parts.

A lunchtime crowd spilled from the cafe onto outdoor tables, where people ate, socialized and worked on laptops. Children from a day camp splashed in Strawberry Creek, while a pair of boys took shots on a basketball court and middle-aged couples played a relaxed game of doubles tennis. In the midst of it all, a family with two dogs cut through the park, using the path that runs along the park’s westerly edge.

Strawberry Creek Park gets even busier on the weekends due to its central location: a five-minute drive from I-80’s University Avenue exit and 12-minute walk from the North Berkeley BART. The mothers group chose the location because it’s within 15 minutes of all the members’ homes.

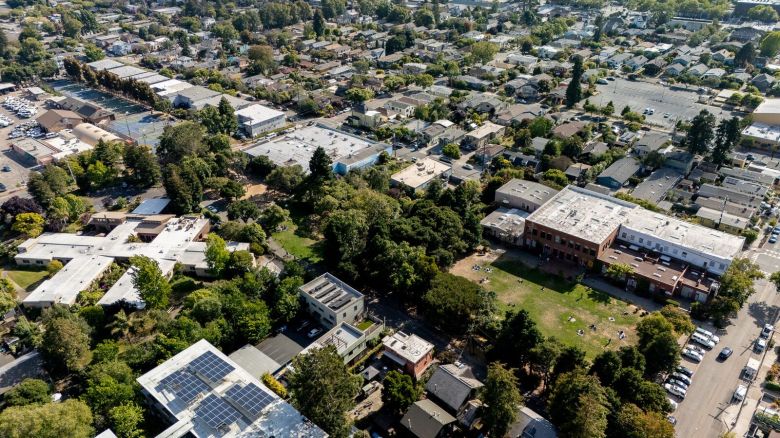

Since its opening in 1983, the four-acre park has also served as a connector to Berkeley’s past. An ancient creek runs through the land, once a Santa Fe Railroad freight yard and right of way that serviced a nearby industrial building in the early 20th century. The corridor has been repurposed to serve what has become a primarily residential neighborhood.

Nicky Deremiah, Madeleine Mountain and Aviana Pedlar picnic with their babies in the park on July 16, 2025. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Nicky Deremiah, Madeleine Mountain and Aviana Pedlar picnic with their babies in the park on July 16, 2025. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

The park’s centerpiece is about 200 feet of Strawberry Creek that was daylighted in 1982, one of the earliest and most successful creek restoration projects — now considered an international model for the rehabilitation of urban waterways.

“This park is significant because it was the community that made it happen,” said John Steere, an environmental planner by training who is president of Berkeley Partners for Parks, a nonprofit umbrella organization that includes Friends of Five Creeks and Friends of Strawberry Creek Park.

A linear park — with fish

Strawberry Creek Park cuts through three blocks of Poet’s Corner. Walking south from Addison Street to Bancroft Way, visitors pass through a spacious green and cross a bridge over the creek before arriving at the playground and, beyond it, a set of basketball, tennis and soccer courts. Credit: Jonathan Hidalgo for Berkeleyside

Strawberry Creek Park cuts through three blocks of Poet’s Corner. Walking south from Addison Street to Bancroft Way, visitors pass through a spacious green and cross a bridge over the creek before arriving at the playground and, beyond it, a set of basketball, tennis and soccer courts. Credit: Jonathan Hidalgo for Berkeleyside

Strawberry Creek is a linear park, a long and narrow slice of land that had been an industrial corridor. The park cuts through three city blocks.

The grassy meadow on Addison Street, the park’s northern boundary, is where the moms spread out with their babies, and others work, read or take in the sun. Such passive recreation is offset by the buzzing activity at the Hidden Cafe, whose French doors in the Strawberry Creek Design Center open onto a patio where patrons sit at metal tables.

“Everybody knows everybody,” said Asako Unome Kellogg, the cafe’s co-owner, who had just said goodbye to a regular customer.

Kellogg owns the cafe with her husband, Andrew, a member of Adelines Lab, a community center that provides a safe and supportive space for artists and small businesses in hospitality and retail. Previously, she operated Chloe Hana Flower, a South Berkeley shop that closed during the pandemic.

Asako Unome-Kellogg, co-owner of The Hidden Cafe in Strawberry Creek park. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Asako Unome-Kellogg, co-owner of The Hidden Cafe in Strawberry Creek park. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Andrew Kellogg opened the cafe with two partners in 2019. The partners backed out during the pandemic, but the cafe has rebounded since, encouraged by neighbors from Strawberry Creek Lodge, a senior community, who have been “our cheerleaders,” Asako said.

“They look out for us and we look out for them,” Asako said.

Like the lodge residents, most of the cafe’s customer base live nearby, but those from farther afield visit on weekends, when the park teems with activity and a nearby parking spot is hard to find.

Simon Trumble, who grew up visiting Strawberry Creek Park, watches his son, Levi, 4, slide down the metal slide July 24, 2025. The city sought to remove the slide for reasons related to safety and liability in 2011, but neighbors fought to save it. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Simon Trumble, who grew up visiting Strawberry Creek Park, watches his son, Levi, 4, slide down the metal slide July 24, 2025. The city sought to remove the slide for reasons related to safety and liability in 2011, but neighbors fought to save it. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Moving south, the park-long path leads to a wooden bridge that traverses the creek, connecting the meadow to a picnic spot and field. Children from a German-immersion summer camp operated by Bay Area Kinderstube played in the creek waters.

“Das ist OK,” Vanessa Fernandez, a camp counselor, told some of the 25 campers who wanted to get closer to the water. The campers visit the park two days a week, walking from its Bancroft Way location. Fernandez’ daughter, Aisling, positioned herself on the banks with a fishing pole — not a far-fetched pursuit.

After 50 years without a trace of fish, native species such as the Sacramento Sucker, California Roach Minnow and Three-spined Stickleback were introduced by UC Berkeley’s Strawberry Creek Restoration Program, according to a 2023 report written by Julia Lambert, an SCRP intern. “These species continue to thrive in Strawberry Creek today,” Lambert wrote. She noted in a phone call that she regularly sees Roach Minnow in the creek.

Ashling, 10, casts for fish in the creek during her summer camp at Strawberry Creek Park. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Ashling, 10, casts for fish in the creek during her summer camp at Strawberry Creek Park. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

The day campers, however, saw no sight of them.

“It’s mostly crawfish,” Fernandez said.

Nevertheless, the park and its creek remain a favorite camp excursion.

“They love it,” she said. “They want to return every year.”

An amenity turned eyesore

The park’s history is deeply intertwined with the creek, rumored to be named for the many strawberry bushes once found along its banks. The creek is the principal watercourse running through Berkeley, flowing westward from its source in Strawberry Canyon in the Pacific Coast Mountain Range and emptying into the bay at the Berkeley Marina. The creek has both a north and a south fork, which meet in a daylit section of creek in the Eucalyptus Grove on the Cal campus.

Lisjan Ohlone people settled along the creek as early as 5,000 B.C., when the creek was flush with salmon, steelhead trout and native shellfish. Discarded shells became a shellmound that once stood near the mouth of Strawberry Creek in West Berkeley, considered one of the most culturally significant sites for the Lisjan people. The city of Berkeley returned the site to Indigenous ownership last year.

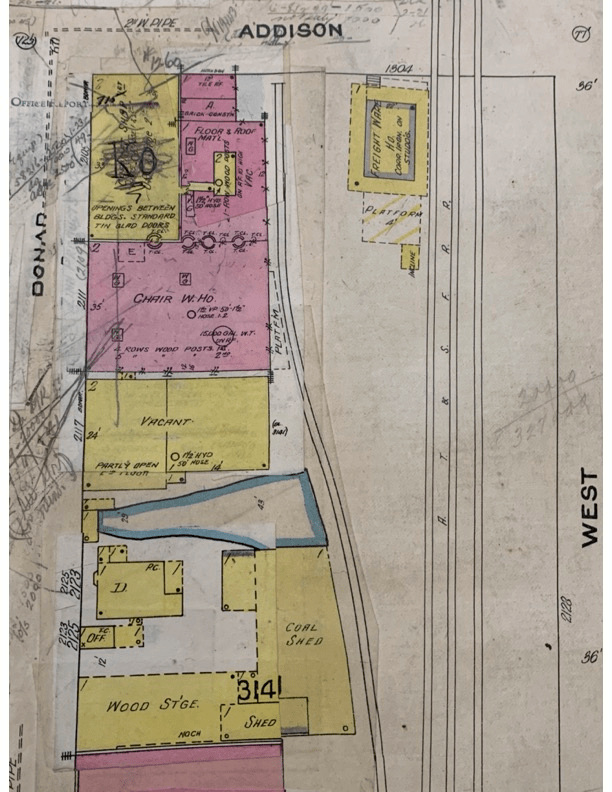

A detail from a 1928-9 fire insurance map showing the site of what is now the Strawberry Creek Design Center and its railroad spur that served early 20th-century factories. Courtesy: Berkeley Public Library History Room

A detail from a 1928-9 fire insurance map showing the site of what is now the Strawberry Creek Design Center and its railroad spur that served early 20th-century factories. Courtesy: Berkeley Public Library History Room

According to Berkeley historian Charles Wollenberg’s Berkeley: A City in History, a Spanish colonial governor led an exploratory expedition along San Francisco Bay’s eastern shore in 1772 and may have camped on the banks of Strawberry Creek, near the university’s west gate, where a monument commemorates the event.

In 1868, the University of California moved its location from Oakland to Berkeley in part because of the benefits of being creekside. By the late 19th century, sewage was being dumped into the creek and by the early 20th century, it had become a depository for trash.

The renowned 19th-century landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, whose campus plan for UC Berkeley was rejected, suggested that Berkeley design its streets to follow existing waterways. That did not happen.

As Berkeley grew, managing the creek — through the use of culverts — in favor of real estate development began in 1883. By the 1930s, most of the creek was covered up by culverts. The fish were gone.

Today, most of Strawberry Creek remains underground, except for sections on the UC Berkeley campus, at the UC Botanical Garden and areas in and adjacent to Strawberry Creek Park.

Reflecting a sea change in the thinking surrounding urban creeks, the city of Berkeley is considering plans to daylight a 300-foot section of the creek to create an “urban oasis” in Civic Center Park. And the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is planning to tear up the old Spenger’s parking lot and daylight the creek along Fourth Street.

The birth of the park and the creek that runs through it

Construction work to daylight Strawberry Creek in 1982. Courtesy: Berkeley Partners for Parks

Construction work to daylight Strawberry Creek in 1982. Courtesy: Berkeley Partners for Parks

The city used some of the tax dollars from 1974’s Measure Y and Land and Water Conservation Fund monies to acquire the former Santa Fe Railroad property and develop Strawberry Creek Park in 1977, according to the Berkeley Gazette.

The property had been used for both freight and passenger service and included railroad tracks, outbuildings and a freight depot that appears in a 1928-29 fire insurance map. What remains of the Santa Fe’s long history in Berkeley is the circa 1904 train station, now the site of the Berkeley School.

The park was the brainchild of Douglas Wolfe, a landscape architect for the city, who also came up with the idea for daylighting the creek. The initial response was not positive.

According to a 2000 report by the Rocky Mountain Institute titled Daylighting: New Life for Buried Streams, “city officials were unsympathetic, fearing the exposed creek would be a flood hazard and a litter-filled eyesore.” Initially, neighbors worried that the project would attract vermin or pose a danger to their children.

Support from activists like Carole Schemmerling Selz and Urban Creeks Council co-founder Ann Riley helped shift public opinion. Citizens ultimately rallied behind the plan, attracting up to 75 people to public meetings, according to the RMI report.

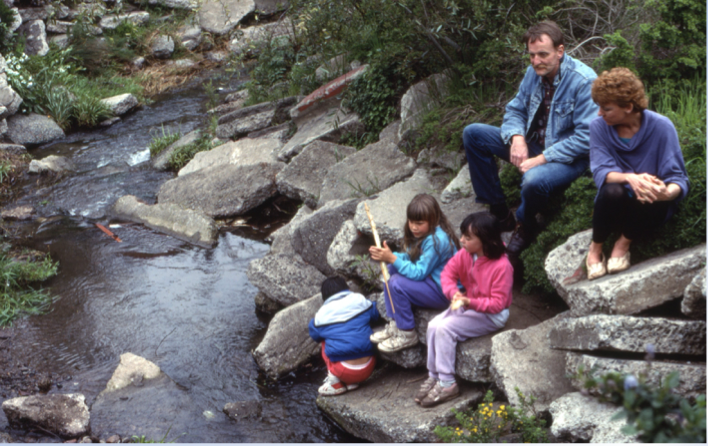

The $580,000 cost to renovate the park (in 1984 dollars) included $50,000 for the daylighting. Design and construction took place from 1982 to 1984. In 1982 crews cracked open the concrete culvert and used the broken pieces to create a series of loosely terraced platforms along the creek’s banks. In another budget-conscious move, most of the displaced soil from daylighting was reused to create berms elsewhere in the park.

Doug Wolfe, the designer of Strawberry Creek Park, and friends at the park in 1989. Courtesy: Berkeley Partners for Parks

Doug Wolfe, the designer of Strawberry Creek Park, and friends at the park in 1989. Courtesy: Berkeley Partners for Parks

The park’s dedication took place on Nov. 5, 1983. It boasts basketball courts, tennis courts, a volleyball court, soccer field, swings and playground equipment, along with a native plant garden that borders the park-long path.

Wolfe’s design would go on to receive the highest environmental planning award in a neighborhood park category from the California Parks and Recreation Society in 1984 and honors from the American Society of Landscape Architects.

A symbiotic relationship with Berkeley Youth Alternatives

Since the park’s beginning, it has been closely aligned with Berkeley Youth Alternatives, whose building borders the park on its western flank, where the east-west Allston Way dead ends. Founded in 1971, BYA provides youth ages 6 to 24 with after-school programs, counseling, career workshops and mentoring programs. Often, some of those activities spill over into the park.

Tiffany Lockett, BYA’s co-executive director, who has worked there for 14 years, affirmed the symbiotic relationship between the nonprofit and the park.

The Berkeley Youth Alternatives building abuts the park by the playground. Credit: Zac Farber/Berkeleyside

The Berkeley Youth Alternatives building abuts the park by the playground. Credit: Zac Farber/Berkeleyside

“Just having access to a safe outdoor space for our kids and families has definitely helped, and access to something like Strawberry Creek,” she said. “The kids love seeing what might be down there. It helps increase their creativity, which is a beautiful thing.”

Lockett realized just how important the park was when the climbing structures were removed around 2019 to make way for an upgrade. “The kids were upset,” she said.

For many years, BYA youth helped to maintain the park, its own orchard/garden space between Bonar Street and the park and a nearby community garden. The landscaping program lost its city funding in 2011 and the two gardens have not recently been maintained by BYA youth.

“We actively use the garden attached to our property, but we haven’t had an internship program there in about a year,” Lockett said, due to budget cuts under previous BYA leadership.

Poet’s Corner is no longer Kamala Harris’ working-class neighborhood

Poet’s Corner has seen many changes in recent decades. Former Vice President Kamala Harris grew up in a home a block from the park, on Bancroft Way, in the 1970s, and described Poet’s Corner as “a working-class neighborhood of firefighters, nurses and construction workers.”

In recent decades skyrocketing housing costs — the median home sold this June for $1.5 million — have reshaped the neighborhood, and its Black population has dwindled, with many residents priced out. Between the 2010 and 2020 U.S. Census, the Black population dropped by half — from 30 percent to 15 percent. The white, Hispanic and Asian populations grew slightly, with the “other” category, which includes people of multiple races, showing the biggest rise, from about 4 percent to 10 percent.

Because of gentrification, BYA’s Lockett said that her organization now has fewer students from the surrounding neighborhood, with more students now coming from elsewhere in Berkeley neighborhoods. Lots of students are bussed from Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School to the center for after-school programs.

Janice Williams, a longtime park neighbor. Credit: Joanne Furio

Janice Williams, a longtime park neighbor. Credit: Joanne Furio

“It’s always been a relatively mixed area,” said Janice Williams, 65, who has lived in the neighborhood since 1963, “when it was an undeveloped tract and all this was a railyard and the [Berkeley] School was a working train station.” She was walking her dog, Harvey, and her neighbor’s dog, Ollie, one Thursday afternoon.

“It is less Black than what it was, but we have had everything in this area, Black, Italian, Asian, Hispanic,” she said. “On San Pablo you could get anything and everything you wanted, from a shoe store to a full-service Italian delicatessen.”

Williams’ family has owned several properties and a liquor store in the neighborhood over the years. Growing up, she used the railyard property as a short-cut to the Berkeley Co-op on University Avenue, which is now a Target.

“When the park first opened, it was a really big deal,” she said, noting that it also happened to be in the midst of the crack epidemic.

“You had that element, but the park wasn’t taken over by them. People knew who they were, where they were and why they were,” Williams said. “I never considered the park unsafe. Crack didn’t keep kids from playing in the park. Just because there was a crackhead sitting on a bench didn’t mean people went screaming out of the park.”

Her own children played in Strawberry Creek Park in the ’90s and her granddaughter does today, but she sees little interaction between Black and white park patrons. “I don’t see a lot of people like me there,” she said. “It cannot be considered a melting pot.”

The Strawberry Creek Park playground in 2022. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

The Strawberry Creek Park playground in 2022. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight Local

Over the years, community members have sought to address the park’s struggles with maintenance and crime.

Williams said the park went through a period of neglect in the early aughts. In 2014, reports of gang violence, public marijuana use, graffiti and a drive-by shooting spurred neighbors to create the Friends of Strawberry Creek Park, which still runs an active listserve. The group advocated for improvements in lighting, tree trimming, maintenance, signage and fencing.

Berkeley Councilmember Terry Taplin, who grew up in the neighborhood and celebrated his early birthday parties at the park in the 1990s, said his predecessor, Darryl Moore, worked with the Friends of Strawberry Creek to improve public safety in the 2010s. He said he continues to work with neighborhood groups to address gun violence.

“I absolutely adore the park and spend much time there, sitting by the creek, reading under the trees overlooking the lawn, sitting at Hidden Cafe, or walking and chatting,” Taplin said. “It really is the heart of the neighborhood.”

The park’s transformation has been aided over the years by the foot traffic generated by the 1987 renovation of the Strawberry Creek Design Center, once home to American Photoplayer Co., which produced music for silent films, Cooper Woodworking and Sperry Flour Company. The frame-and-brick building once had its own railroad spur line, laid in 1903, that made shipping convenient for its tenants.

The building is now home to some 40 small businesses, from creative companies like Ogle Architecture & Design, which leaves its French doors facing the park open, to the Phoenix Pastificio, a fresh pasta shop that also sells baked goods, and Transit Books, a publisher of international and American literature. Transit publisher Adam Levy fell in love with the park when visiting with his children one Saturday and then moved his offices into the building in March 2024.

Al Davidson takes his paralyzed corgi Saki to sit by Strawberry Creek and admire the view. File photo: Zac Farber/Berkeleyside

Al Davidson takes his paralyzed corgi Saki to sit by Strawberry Creek and admire the view. File photo: Zac Farber/Berkeleyside

“The park itself is absolutely an amenity,” Levy said. “We sometimes take meetings in the park. Our executive editor, Lizzie Davis, recently brought in a bocce set, so our staff can sometimes be seen there playing a quick game.”

Steere noted that the park has gotten more popular over time. “The design center has really brought commercial and pedestrian life into the park as well,” he said.

Bancroft Community Garden is right at the end of the park

Fresh fruit, vegetables and herbs are available for free or by donation to visitors of the Bancroft Community Garden. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Fresh fruit, vegetables and herbs are available for free or by donation to visitors of the Bancroft Community Garden. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Strawberry Creek Park officially stops at Bancroft Way, but the Bancroft Community Garden across the street feels like a natural endpoint. Owned by the city and managed by a fleet of volunteers (though it’s still leased to BYA), the garden has been growing organic produce since 1994.

The three-quarters-of-an-acre boasts about 40 fruit trees, plots of vegetables and herbs and native plants like monkey flower, the musky fragrance of which greets visitors at the garden’s entrance.

Nearby residents — who may not have a yard of their own — rent, grow and maintain their own plants and vegetables on 36 individual plots for $40 annually. (There’s a years-long waitlist.)

Steve Moros, coordinator of the Bancroft Community Garden, on July 16. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

Steve Moros, coordinator of the Bancroft Community Garden, on July 16. Credit: Sara Martin/Berkeleyside

On a table at the entrance, a handful of fresh-picked organic plums were some of the produce recently offered for free or by donation.

Steve Moros, the garden’s coordinator, said the hundred or so visitors who meander through the lush grounds on any given week “come for the fresh produce and the donated seedlings,” as well as peace of mind. “A lot of nannies come in here with their kids and just hang out,” he said.

Moros also has a connection to the park. He was a core member of the Friends of Strawberry Creek Park, which contributed to a paradigm shift.

The park is now in “good shape,” he said, the result of decades of community involvement.

Let’s be real …

These are uncertain times. Democracy is under threat in myriad ways, including the right of a free press to report the truth without fear of repercussions.

One thing is certain, however: Berkeleyside was built for moments like these. We believe wholeheartedly that an informed community is a strong community, so we’re doubling down on our mission of reporting the stories that empower and connect you when it matters most.

If you value the news you read in this article, please help us keep it going strong in 2026.

We’ve set a goal to raise $180,000 by year-end and we’re counting on our readers to help us get there. And a bonus: Any gift you make will be matched through Dec. 31 — so $50 becomes $100, $200 becomes $400. Will you make a donation now in support of nonprofit journalism for Berkeley?

Tracey Taylor

Co-founder, Berkeleyside

“*” indicates required fields