In a neighborhood stuffed with pizza joints and drowning in cappuccino cafes, how lovely to come upon a store devoted to one beautiful instrument: Flute World.

At the corner of Union and Grant streets, it features high ceilings, natural light spilling in from tall windows, displays of instruments, musical cases, accessories, and the Zenbooth, a private space crafted in Berkeley to test out flutes.

Why, among woodwinds, does the flute hold such an exalted place? The great French flutist Jean Pierre Rampal, who popularized the instrument after WWII, said it expressed “the sound of humanity … playing the flute is not as direct as singing, but it’s nearly the same.”

Cyron Jed Bejasa. Photo by Colin Campbell.

Cyron Jed Bejasa. Photo by Colin Campbell.

That’s a view apparently shared by William Underwood and Cyron Jed Bejasa, two veteran flutists who preside over Flute World.

The business is a one-stop shop where musicians of all ages and levels of expertise can buy C-flutes (the standard Western flute, in key C), piccolos, and alto and bass flutes, where they can bring their instruments for servicing, where they can peruse boxes of sheet music and where, on one autumn afternoon, they could attend a performance and master class with world-renowned jazz flutist Ali Ryerson.

The shop opened here in 2019 as a branch of the flagship Flute World, established in the early 1980s by Detroit Symphony Orchestra flutist Shaul Ben-Meir.

Originally a resource for sheet music (most music publishers were European, so it was hard to find pre-Internet), Flute World expanded into a business and resource, concentrating on flutes.

It was bought in 2015 by the J.L. Smith Group (Jeff Smith, a leader in the instrument service industry and his flutist wife, Sarah). They added stores in Charlotte, North Carolina, and in North Beach.

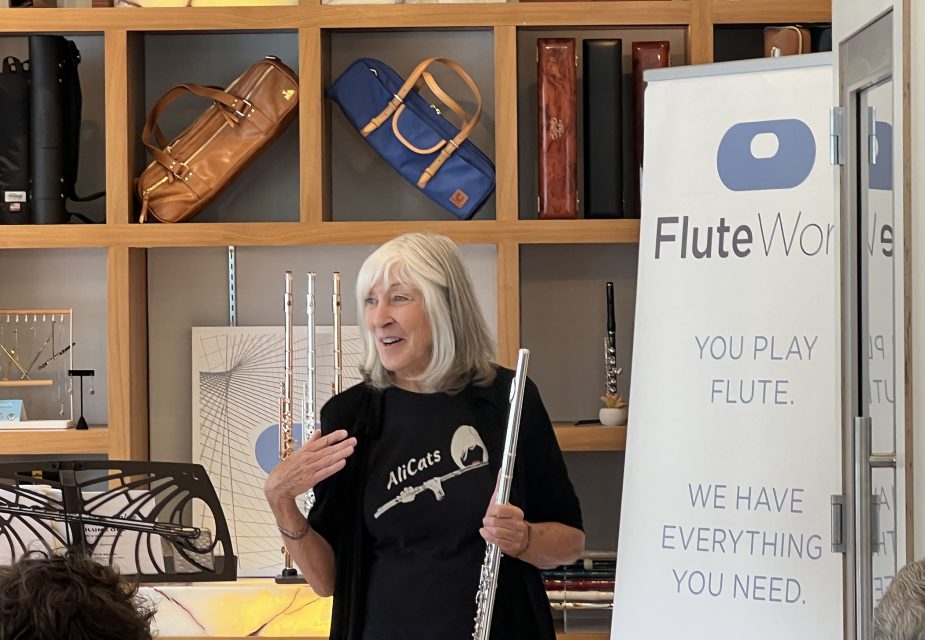

Ali Ryerson, jazz flutist at Flute World. Photo by Colin Campbell.

Ali Ryerson, jazz flutist at Flute World. Photo by Colin Campbell.

Underwood’s history with the flute goes back to his boyhood in Detroit where his dad played saxophone and his mom played the flute. “I wanted to play clarinet or trumpet, but I had too big an overbite and could not produce a sound. When I tried the flute, I could make a pure sound, so I’ve always felt like the flute chose me!”

Underwood attended an HBCU, Florida A&M, playing both in the wind symphony and their renowned band, “The Marching 100.”

He completed a master’s degree in flute performance back in Michigan, at Wayne State University, and then toured several summers in Japan, performing onstage in a high-energy revue of Disney and Anime tunes. Then, Flute World in Detroit recruited him to San Francisco.

Underwood’s calm and gracious manner also makes him perfect as an event host, a role he filled recently at Flute World’s Christmastime flute choir play-along, led by Pacifica-based flutist and teacher Gail Edwards. “She’s the flutiest flute lady I know,” Underwood says.

Edwards returns the compliment.

“Having Flute World move to San Francisco is like a dream come true,” she says. While she praises the service and the staff, she adds, “perhaps the most valuable resource that Flute World provides is the camaraderie and connections one makes on each visit.”

You can often hear Cyron Jed Bejasa before you see him, as he frequently tests out flutes he is working on at the open window. Raised in Burbank in a non-musical family, Bejasa found his own way to the flute.

“From the moment I started playing the flute in middle-school band, I knew from day one that this was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.

“I remember saving up my lunch money to pay for private lessons. And then my band director said, ’Oh, don’t pay me. Just come see me during lunch hour,’ and we would sight-read duets during the break.”

He credits her generosity and his own tenacity — “she noticed how much I practiced” — for his early success.

Coincidentally, Bejasa’s neighbor was a flutist with the L.A. Opera, “So I had two flute moms growing up. I was always asking for flute fingerings, it was always me seeking it out. “

During high school, he became principal flutist with the Los Angeles Youth Orchestra.

His interest in flute repair began with his own flute technician, Paul Rabinov, one of the most respected in the field, who often let him sit beside him on the bench.

“He would show me his repairs step-by-step and talk about the history of flutes, their makers, and the lineage of the craft. Watching him, I came to see repair as more than just ‘fixing’ instruments. It’s a technical, creative, artistic, and musical discipline, requiring as much sensitivity as performance itself.”

Bejasa came north for the orchestral program at the University of California, Berkeley, graduating with a degree in music. Then he dove into the Bay Area freelance scene: Pit orchestras, symphony subs, chamber concerts, and teaching.

“I built a private flute studio of about 20 students and worked with several school districts. Many of those schools had flutes in poor condition and little funding for repairs. That challenge helped me sharpen my repair skills quickly. I ended up servicing hundreds of school flutes, making them playable for the next generation.”

Bejasa was at Flute World’s opening day in San Francisco, and remembers seeing the empty space intended for the technician. He thought to himself, “What a dream job!” Now it’s his.

“The clients I work with are often high-level players who rely on the flute for their livelihood. If the instrument doesn’t feel easy to play, or if certain notes are not sounding in tune and require extra effort, it is my role to ensure the flute is in optimal performance condition, so they can play with comfort and confidence.”

An annual flute service takes meticulous, time-consuming, old-school craftsmanship.

For a professional musician who dropped off her flute recently, for example, says Bejasa, “I completely disassembled the instrument, removed dents and scratches on the silver tube, cleaned, lubricated, and polished the mechanism, and replaced five pads.

“But the most important — and perhaps the most methodical — part of the work was making sure every pad achieved a truly hermetic seal at first touch. Even a tiny leak can negatively affect the performance of the instrument. Precision and care matter at every step.”

Underwood is equally devoted. Though Flute World is closed on Sundays, he recounts, “A local professional player, in search of a new piccolo, needed to visit on a recent Sunday due to her demanding schedule. How could I not make myself available?

“This is a resource for our community. As a flute player myself, it was an honor to help her. This is honorable work.”