On a recent crisp winter afternoon in Pacific Palisades, the stillness of an abandoned community buzzes with the banging, whirring, thumping sounds that accompany new construction. Honey-colored plywood hulks dot the devastated landscape, where in front of one recently poured foundation a bush blooms with a cranberry-hued flower as a sign of hope in a place where one year ago, on Jan. 7, a blaze exploded at 10:30 a.m., fueled by Santa Ana winds. It soon became what the Los Angeles Fire Department calls “California’s 10th-deadliest and third-most-destructive vegetation fire,” one that would mark the “most catastrophic wind-driven vegetation fire in the City of Los Angeles.” When it was over, 5,800 homes were reduced to ash. Another 1,000 businesses — supermarkets, churches, schools, delis, the small-town businesses that made the Palisades the tight-knit community of celebrities and civil servants alike — were turned to rubble. Twelve people died.

For all that was lost, much was saved. Thousands of people in the burn zone were ushered to safety in chaotic but successful evacuations from the hills to the sea. According to Cal Fire (the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection), 12,317 structures that were deemed “threatened” during the fire avoided destruction. As molten embers rained down in a ferocious firestorm, firefighters risked their lives to hold the line in the face of hurricane-force winds. They kept fighting even when they ran out of water and when hydrants were tapped dry. They fought to keep their own house — Fire Station 69 — from burning with what little water they had on their rigs.

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

All the destruction began, federal prosecutors now say, when an alleged arsonist named Jonathan Rinderknecht, a former Palisades resident and Uber driver who hiked into Topanga State Park in the first few minutes of the new year and held a long lighter to dried brush, started what became known as the Lachman fire. Inexplicably, it continued to smolder, reigniting a week later and ravaging not only Pacific Palisades but massive swaths of Malibu, where 240 homes along the coastline burned, as well as parts of Topanga Canyon. The fight against the Palisades fire became a relentless, quixotic battle for first responders that raged on, the LAFD After-Action Review Report states, until Jan. 31.

“This deadly fire, fueled by category 1 hurricane winds, was among a series of 11 wind-driven fires that occurred over the next three weeks, devastating the Southern California region,” LAFD officials wrote in the report. “The Palisades Fire would eventually scorch 23,448 acres, tragically resulting in 12 fatalities.”

Credit: Los Angeles Magazine

Credit: Los Angeles Magazine

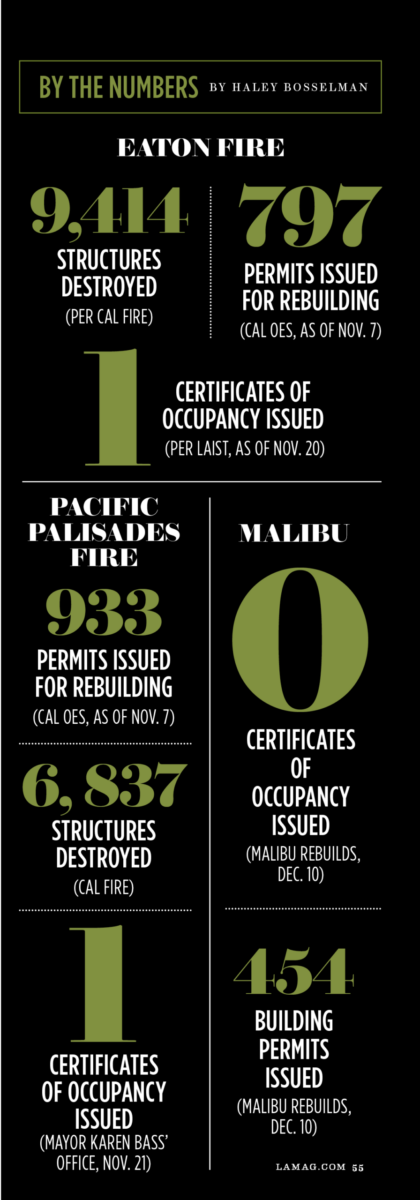

But in the long months since, residents who lost everything in the fire have been waging their own quixotic battle to return home. According to statistics compiled by Los Angeles, not a single individual whose house burned has been able to return to the community. In Pacific Palisades, only one certificate of occupancy has been issued, and that house was in the process of being rebuilt before the fire. Another 933 rebuilding permits have been issued. In Malibu, there have been no certificates of occupancy permits issued and only 454 building permits issued.

In October, after the arrest of the suspected arsonist was announced, City Councilmember Traci Park and multiple families who were gravely impacted by the blaze remained furious, and not just at the accused criminal, who continues to be held without bail. They cited unrelenting insurance shenanigans, endless bureaucratic red tape — and fury that foreign entities and hedge funds have anonymously begun buying up burn-scarred lots from families who have given up hope of returning to their former lives. The arrest of Rinderknecht, Palisades resident Allison Polhill told Los Angeles that afternoon, “didn’t bring peace,” nor did it answer questions about what she called the city’s negligence in letting a reservoir dry up and hydrants go untested. “It opened a wound, because him setting that fire is not an explanation as to why my house burned down.”

Scroll to continue reading

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

In Altadena, there is similar frustration. In that historic community, 19 people, many of them elderly or infirm, died in the wake of the Eaton fire. There were scant evacuation warnings. A separate report commissioned by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors said the losses were unimaginable and recognized missteps by both city and county political figures. Weaknesses found, they said in a statement, included “outdated policies, inconsistent practices and communications vulnerabilities” that hampered firefighters battling the fire, which was moving with lightning speed through the historic neighborhood. “While frontline responders acted decisively and, in many cases, heroically, in the face of extraordinary conditions, the events underscored the need for clearer policies, stronger training, integrated tools, and improved public communication,” the report said.

No arson has been alleged as a cause of the Eaton fire; rather it appears to have been started by a fallen power line. In the early morning hours of Jan. 8, county fire officials transmitted a call that they had “eyes on a fire in the foothills north of Farnsworth Park above Lake Avenue and that the fire front appeared to be moving west along the foothills,” Los Angeles County officials reported. By then, many of the community’s resources had moved west to assist in fighting the Palisades fire, leaving large parts of Altadena unprotected until firefighters could race back.

In the meantime, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Deputies and other first responders went to work evacuating nursing homes and getting as many people as possible to safety, pushing through walls of thick black smoke to get people out as the fireball raced toward them. Like Fire Station 69, an L.A. County Sheriff’s Department station in Altadena was threatened. Some homeowners stayed behind, many of them in generational homes, desperately trying to save what their grandparents had built, and left to fight with garden hoses. A total of 9,414 homes and businesses were destroyed, and Altadena residents are also facing an uphill battle to return to their community. Just like in Pacific Palisades, only a single certificate of occupancy has been issued. While there have been 797 building permits issued, they represent only a fraction of what was lost.

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

Credit: Irvin Rivera

“Many are waiting to see if their neighbors rebuild, some want to know if local businesses and services will return, and most are stuck figuring out how to pay for rebuilding because of financial barriers like underinsurance, little to no government support or the high cost of construction,” says Lori Gay, president and CEO at Neighborhood Housing Services of Los Angeles County.

Still, last month, hope lit up one area affected by the Eaton fire — literally — as more than 150 homes and 300 trees marked the holiday season on Christmas Tree Lane — the famous nearly mile-long stretch of deodar cedars in Altadena that miraculously didn’t burn. In a year filled with so much loss and despair, it demonstrated the resilience of a neighborhood beloved by so many.