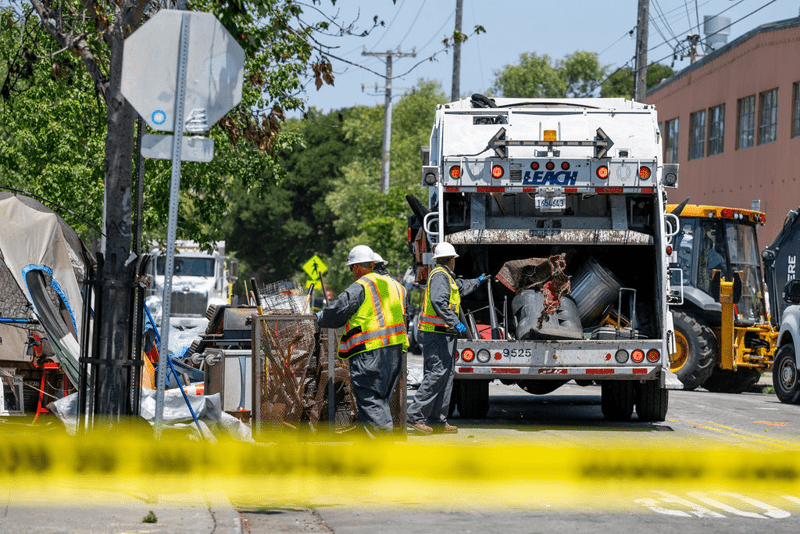

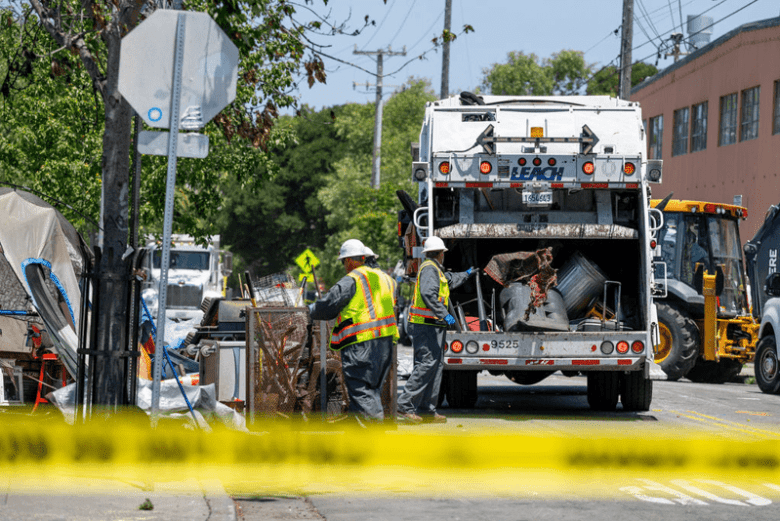

City workers remove tents and other belongings during an operation to clear the camp last June. Credit: Adahlia Cole for Berkeleyside

City workers remove tents and other belongings during an operation to clear the camp last June. Credit: Adahlia Cole for Berkeleyside

Berkeley’s public health officer says people and pets in Northwest Berkeley are at risk from an outbreak of leptospirosis that has circulated among dogs and rats at the longstanding encampment of tents, RVs and other shelters around Eighth and Harrison streets.

Veterinarians found leptospirosis in two dogs living in the camp in November, so county health workers began trapping and testing rats living in the area, according to a notice posted Monday by Dr. Noemi Doohan, Berkeley’s public health officer. Those tests found the bacterium in rats for the first time anywhere in Alameda County in the last five years, Doohan said.

Berkeley officials have long wanted to remove the encampment, but a federal judge has temporarily blocked the city from ousting a few of the camp’s residents since June, pending the resolutions of their disability accommodations claims — a process that has missed deadline after deadline. Theoretically the city is free to evict other campers, but city health officials and attorneys say that unless the entire camp leaves for at least 30 days, health workers cannot fully eradicate the rat burrows in the area, meaning the outbreak will persist.

“It is important to note that leptospirosis is considered a ‘neglected tropical disease’ which is prevalent in underdeveloped tropical countries,” Doohan, who has worked in Haiti and Ethiopia and said she was quite familiar with this type of illness, wrote in a court filing. “Leptospirosis is rare in developed countries … the exception is homeless encampments in the U.S. which are considered high risk for rat infestations.”

Judge Edward Chen left the prohibition in place during a hearing about the encampment in federal court Tuesday, but said that a final determination was likely soon.

Anthony Prince, an attorney for the Berkeley Homeless Union, which filed the Americans with Disabilities Act lawsuit last year, said the only reason disease-bearing rats were gathering near the camp in the first place was that the city removed a dumpster in June and never brought it back.

“For the profoundly disabled residents of the Harrison Corridor, the trauma and instability of forced displacement — including the loss of shelter, community and medical equipment — poses a far more immediate and severe threat to life and health” than the outbreak, Prince and BHU President Yesica Prado wrote in a court filing Tuesday.

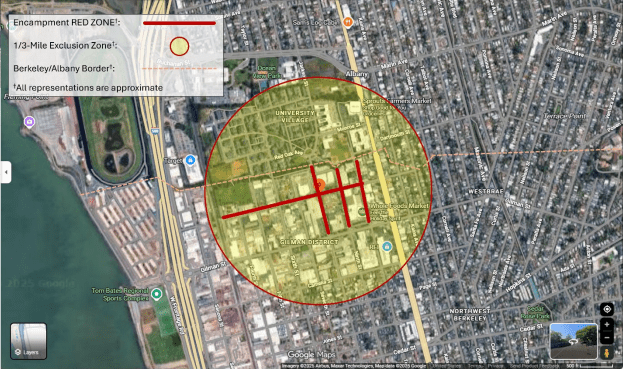

Berkeley has not yet tested Codornices Creek for leptospirosis, Doohan wrote in a court filing. However the city recommended that people consider the creek and any standing water within a third of a mile of the camp as contaminated. The bacterium travels through water by way of infected urine, and infects people and animals who come into contact with contaminated water or urine.

Berkeley health officials have said everyone camped in the “red zone” blocks in the center of the map clear out as soon as possible, and that leptospirosis could be present up to a third of a mile around, as indicated by the yellow circle. Credit: City of Berkeley

Berkeley health officials have said everyone camped in the “red zone” blocks in the center of the map clear out as soon as possible, and that leptospirosis could be present up to a third of a mile around, as indicated by the yellow circle. Credit: City of Berkeley

In humans, leptospirosis typically causes fevers and headaches, aches, chills, nausea and vomiting, jaundice, red eyes, diarrhea and rashes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Many people never show symptoms, but since so many of the symptoms are common in other illnesses, the disease is sometimes misidentified. It can be treated with antibiotics but, if untreated, can result in organ failure, meningitis and occasionally death.

Leptospirosis can be fatal to dogs as well, presenting first with excessive thirst, vomiting, shivering and lethargy, Doohan wrote in a Jan. 6 court filing. The city has recommended dog owners make sure their pets are up to date with vaccines, and has offered vaccine vouchers for camp residents.

Infected animals can continue to urinate the bacterium for months or even years, and it can live on in contaminated water for months longer, according to the CDC.

The encampment, which some neighbors and nearby businesses have complained has been the epicenter of dangerous fires, rampant drug use and other dangers, has been the subject of several lawsuits. Some have sought to block attempts to clear out the camp. Another still-pending lawsuit in state superior court, filed by a coalition of business owners and residents, has accused Berkeley of allowing public nuisances to persist at the camp.

Three disabled camp residents filed a lawsuit in early 2024 accusing the city of violating ADA requirements when it ordered everyone to leave the area, and the BHU joined the case as a plaintiff. When the city moved to clear the camp last June, Judge Edward Chen granted BHU’s request to temporarily put a stop to the closure.

Chen later pared back that order by saying the sweep could go ahead, but ordering that campers with outstanding ADA claims be allowed to remain. The grace period for those campers was meant to last 60 days, but those claims remain unresolved seven months later.

At the hearing Tuesday, Chen said that whatever the holdup was in the ADA negotiations, the time was near for him to rule one way or another on whether the city could close the camp. He ordered the attorneys for BHU and Berkeley to submit arguments for a hearing March 20.

“I think we’ve spent enough time going back and forth,” he said.

“*” indicates required fields