Live Free team members (from left, Ben Knight, credible messenger; Kentrell Killens, field services director; Twin Damaria Johnson, life coach and outreach worker; Abdul Wayne, credible messenger; Todd Walker, life coach and outreach worker; and Senon “Snoop” Nails, credible messenger) outside the organization’s Berkeley headquarters. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Live Free team members (from left, Ben Knight, credible messenger; Kentrell Killens, field services director; Twin Damaria Johnson, life coach and outreach worker; Abdul Wayne, credible messenger; Todd Walker, life coach and outreach worker; and Senon “Snoop” Nails, credible messenger) outside the organization’s Berkeley headquarters. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Gun violence in Berkeley last year hit the lowest point since the police department first started publishing data on it nearly a decade ago, reflecting local and national trends. A network of violence intervention workers, faith leaders and volunteers has been working to keep the numbers down, but their pilot program is only funded for another six months.

According to Berkeley police data, the number of shootings — any time a gun is fired in the city, regardless of whether anyone is injured or killed — increased steadily for five years beginning in 2017, the first year the agency made data available online. After peaking at 53 incidents in 2022, the trend reversed itself over the next three years, falling to 15 in 2025.

Homicides are so rare in Berkeley as to make it difficult to identify any trends; in the same time period they yo-yoed between zero and eight in any given year. In 2025 there was just one, a fatal stabbing last January, compared to four in 2024, three of which were by firearm.

The city’s most recent fatal shooting was more than 16 months ago, in August 2024, the same month Berkeley announced a two-year contract with the East Bay-based nonprofit Live Free USA. Led by The Way Christian Center’s Rev. Michael McBride, the national organization has been working ever since to reduce shootings in Berkeley by treating gun violence as a public health crisis. Its street outreach workers coach about two-dozen people — sometimes victims and their friends and families, sometimes those suspected of or likely to commit gun violence, sometimes both at once, at all hours of the day or night and often for hours at a time.

The work takes coaches all over the Bay Area, since Berkeley shootings are not always the result of Berkeley grudges.

“We’ve been able to have a footprint and make connections in the city of Richmond, Vallejo, Oakland and Antioch, Stockton,” said Kentrell Killens, a field services director with Live Free.

Officially known as the city’s Gun Violence Intervention and Prevention Program, Live Free’s work in Berkeley is similar to programs like Oakland’s Ceasefire, which city leaders there credit in part for a massive reduction in homicides and other violent crimes.

Kentrell Killens, field services director, outside the Live Free office in Berkeley on Jan. 12, 2026. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Kentrell Killens, field services director, outside the Live Free office in Berkeley on Jan. 12, 2026. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Live Free’s coaches have had over 1,000 sessions and check-ins with the 25 people targeted for interventions since they began their work. And they have made hundreds more overtures and interventions — mediating longstanding feuds before they can turn violent, visiting people at the Santa Rita Jail in Dublin, connecting people with crisis and other services, visiting schools and attending funerals. They’ve also run or helped with hundreds of crisis interventions and dozens of healing events, like memorials and vigils, and training sessions for new leaders in violence prevention.

When the coaches are trying to talk someone out of violence, they say their most useful tool is the truth.

“Listen to us or you’re going to jail, bottom line. You’re going to get killed,” said Todd Walker, a street outreach worker and life coach for Live Free. “You’re going to leave your little baby to somebody else to raise … your grandparents’ house is going to get raided, they’re going to get evicted. You got to just tell them the truth.”

Decline in shootings tracks with national trend

The years-long rise, and subsequent years-long fall, of gun violence in Berkeley roughly tracks a national pattern. Shooting deaths and injuries in the U.S. have both dropped for four years straight, ever since they peaked in 2021, according to a recent report by The Trace. Shooting deaths in the U.S. are the lowest they’ve been since 2015; injuries, since 2014. The Trace noted that more and more states have invested in violence prevention, but the Trump administration has cut $819 million in violence prevention and public safety grants.

Berkeley officials have said it’s impossible to tie the city’s gun violence trends to one specific factor, and that they are instead interwoven with other criminal, economic and enforcement shifts, community work, and state and federal policy changes, among other things.

Todd Walker (center), Live Free life coach and outreach worker, attends a check-in meeting with his team at the organization’s Berkeley headquarters, on Jan. 12, 2026. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Todd Walker (center), Live Free life coach and outreach worker, attends a check-in meeting with his team at the organization’s Berkeley headquarters, on Jan. 12, 2026. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Killens, too, acknowledged there was a complex web of overlapping circumstances that affected rates of gun violence — people in recent decades have been more willing to go to guns rather than fists, he said, and gun sales spiked in the pandemic years, around the time that gunfire incidents in Berkeley hit their peak.

But evidence from Oakland indicates that prevention programs seem to work. A 2018 study there credited Ceasefire for reducing homicides by 31% and shootings by 20% over five years. (The city gradually disinvested in the program beginning in 2016, but began reinvesting in 2024, corresponding with the more recent downward trend in shootings and homicides there.)

Whether or not it’s possible to quantify precisely how Live Free has contributed to Berkeley’s drop in shootings, Killens is confident that it has.

“This is something that the city of Berkeley hasn’t ever had,” Killens said. Their success, he said, relies on Live Free’s life coaches but also faith leaders and other community figures “who’ve got great relationships with people and can get to folks in the right amount of time. It definitely decreases the potential for some situations to continue to escalate.”

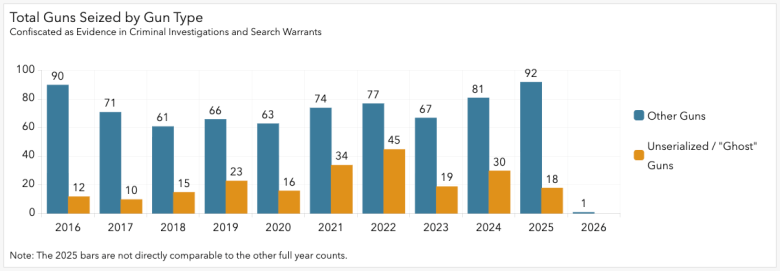

Other BPD data show there are still firearms on the city’s streets: While gun violence steadily rose and then steadily fell, gun seizures in Berkeley have oscillated less predictably. Police seized between 76 and 122 firearms each year.

Gun seizures by BPD do not seem to directly correspond to instances of gun violence in the city. Credit: City of Berkeley

Gun seizures by BPD do not seem to directly correspond to instances of gun violence in the city. Credit: City of Berkeley

“Over the last decade, handguns have remained the most common recovery, though we saw a notable surge in ghost guns between 2020 and 2022 followed by a decline in the years since,” Carianna Arredondo, an assistant to the city manager, said in an email. Arredondo is the city manager’s office’s point person for Reimagining Public Safety, an initiative that began in 2020, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, to change how Berkeley conducts traffic and criminal investigations, crisis outreach and behavioral health work.

BPD’s annual gun seizures far outstripped cases of gun violence, which Arredondo said reflected “our ongoing commitment to proactive enforcement and thorough investigations.”

(BPD’s data do not include shootings within Berkeley that are investigated by the California Highway Patrol, university police or other agencies.)

Berkeley’s first shooting of 2026 was last Friday, a month after the final shooting of 2025. By comparison, in Richmond, where the city also celebrated a historically low homicide rate in 2025, there was nevertheless a huge spike in shootings in the final quarter of the year.

Program gets buy-in from community and police

Live Free’s work relies on its network of relationships. Officially, the city has only contracted with Live Free, but the Oakland-based National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform is a subcontractor in the program, responsible for training and analysis. Killens and Walker are both members of Rev. Michael Smith’s McGee Avenue Baptist Church in South Berkeley, where the Voices Against Violence program has been doing prevention work for years already.

“It’s not just enough to talk about community violence intervention,” said Smith, who is also executive director of the Center for Food, Faith and Justice, which works to connect people with services. “They may need counseling support, they may need food support, they may need job training.

”If it’s beyond our capacity, we want to always be in a place where we can provide the proper referrals.”

The training often focuses on amplifying the Live Free USA coaches’ message of violence prevention.

People dance in the street at the “Stop the Violence National Night out Block Party,” hosted by the McGee Avenue Baptist Church and city of Berkeley, in South Berkeley. Credit: Daniel Ekonde/Berkeleyside

People dance in the street at the “Stop the Violence National Night out Block Party,” hosted by the McGee Avenue Baptist Church and city of Berkeley, in South Berkeley. Credit: Daniel Ekonde/Berkeleyside

“Some of the people who make the best life coaches [are] people who were once on somebody else’s caseload,” Killens said. “Some of them have been in the penitentiary, some of them have … lost loved ones to gun violence or been the perpetrators of violence.”

Killens, Walker and the other outreach workers all have deep ties to the East Bay, and most to Berkeley specifically. The truth is a useful tool, but so is their familiarity with body language, specific neighbors and specific grudges.

Most importantly, the coaches have to trade on their integrity. The people they contact have to be able to rely on the coaches to keep confidence. For that reason, while the coaches may get referrals from police, information never flows the other way.

“We’ve got to go home at night, we don’t have the luxury of a gun and a vest, all we have is our credibility and our name,” Killens said. “If anything compromises that, there goes the success of this program.”

Killens and Walker said BPD generally, and Chief Jen Louis specifically, have embraced prevention work in a way that other agencies — and even previous BPD chiefs — have not.

“Regardless of BPD’s history, or historic challenges among Black communities, what we have seen is their super willingness to embrace this program, to support where we are,” Killens said. “We hear them saying to their own staff, ‘We have one-way conversations with Todd and Kentrell … we’re not going to compromise their integrity in the work by trying to get them to tell us who did a shooting.’”

Kentrell Killens, field services director, right, speaks to his Live Free team (from left, Abdul Wayne, credible messenger; Todd Walker, life coach and outreach worker; Twin Damaria Johnson, life coach and outreach worker; Ben Knight, credible messenger; Senon “Snoop” Nails, credible messenger) about an upcoming training on the power of focusing on impacted families’ strengths rather than struggles at the organization’s Berkeley headquarters. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Kentrell Killens, field services director, right, speaks to his Live Free team (from left, Abdul Wayne, credible messenger; Todd Walker, life coach and outreach worker; Twin Damaria Johnson, life coach and outreach worker; Ben Knight, credible messenger; Senon “Snoop” Nails, credible messenger) about an upcoming training on the power of focusing on impacted families’ strengths rather than struggles at the organization’s Berkeley headquarters. Credit: Florence Middleton for Berkeleyside

Future funding is an open question

Live Free’s pilot contract, which runs through July, came after years of study. Councilmember Terry Taplin, who represents Southwest Berkeley, sponsored budget referrals for $200,000 for consulting in 2021 and $1 million for staffing in 2022.

The city initially set aside $2 million for Live Free and NICJR beginning in August 2024. The California Board of State and Community Corrections awarded Berkeley an additional $1 million grant last summer, of which about $400,000 will go to Live Free to fund another life coach position, crisis services and staff training. (The balance will fund civilian staff and technology upgrades for BPD.) The extra funding should mean that between 50 and 75 people “will receive direct engagement and services,” according to the city’s application for the grant funding.

But the pilot period will run out later this year, around the time the City Council will have to approve a new budget in the face of a projected $28 million structural deficit.

Arredondo said that there was no long-term funding source for the program locked down yet, and that while the city was looking for state and federal funding, “recent changes in federal grant requirements have introduced additional constraints for municipalities with sanctuary city policies” like Berkeley.

Nevertheless, she said, “certain private foundation opportunities are better suited for Live Free to pursue directly.”

And Live Free has been doing just that, seeking out funding on its own, but hoping for long-term commitments from the city.

“We are looking for the city to also look at ways to help sustain this work,” Killens said, “because the work that we’re doing is absolutely a part of public safety work.”

“*” indicates required fields