On the Shelf

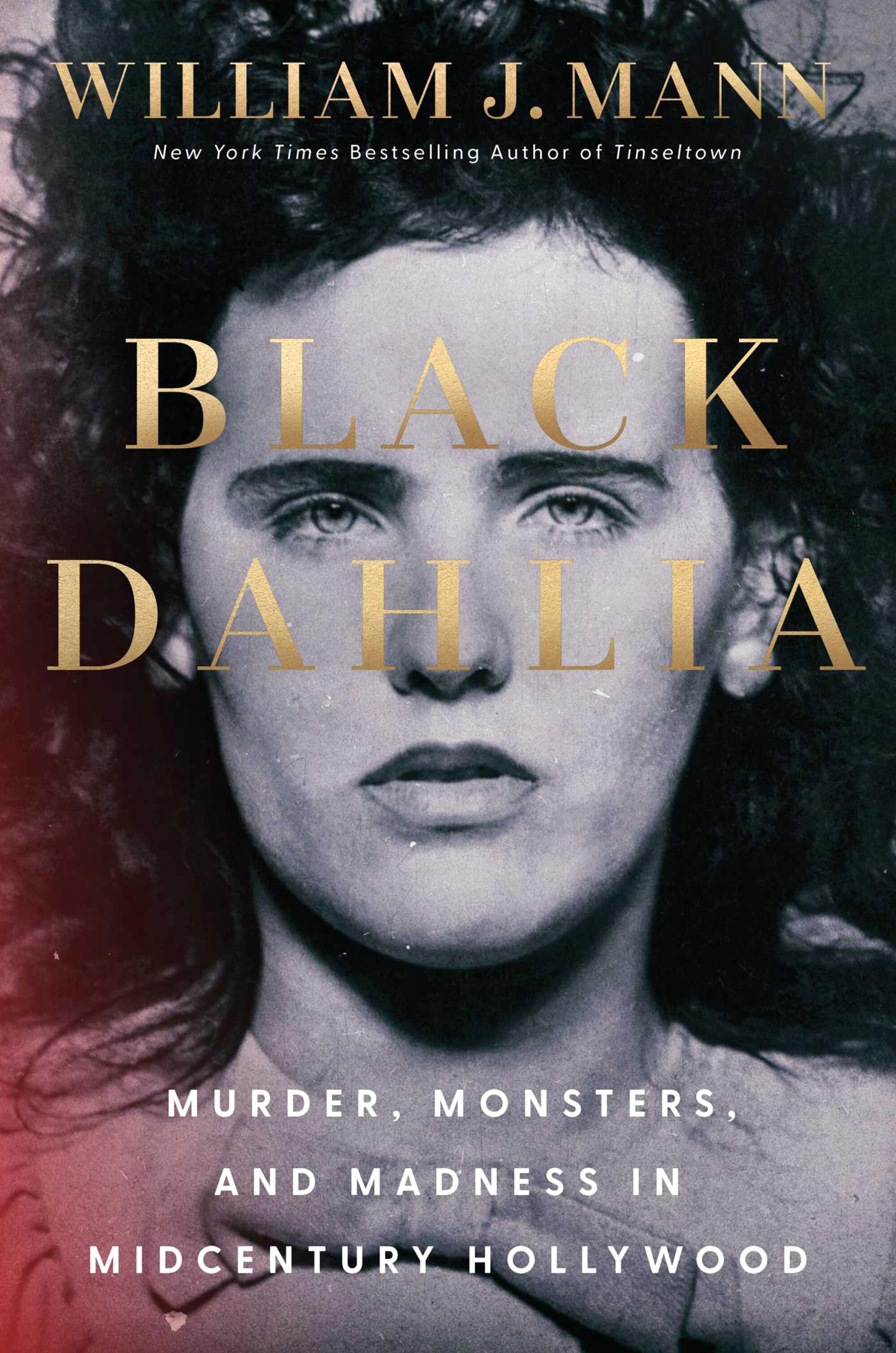

Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood

By William J. Mann

Simon & Schuster: 464 pages, $31

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

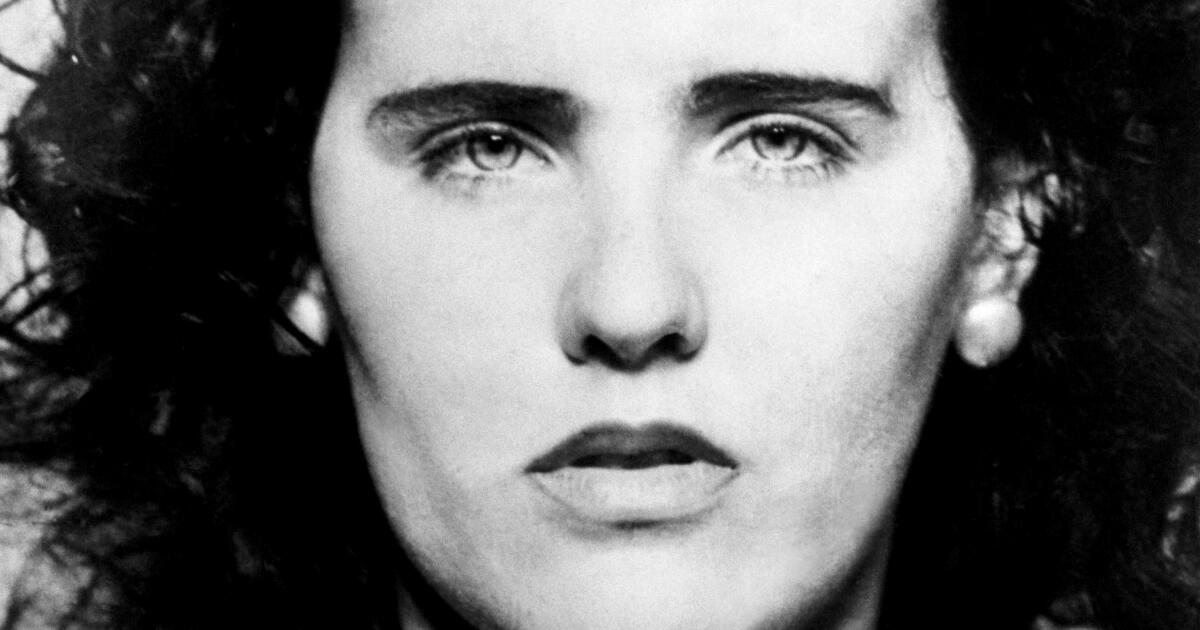

At 21, wanderlust — that aching desire to escape to somewhere else — took hold of Elizabeth Short.

Medford may have been her home, but Los Angeles was salvation, a bustling city the young woman arrived in the late summer of 1946 just after her birthday. Some friends heard that she had plans to become a model, others that she wanted to become an actress. Her immediate goal was simply to find freedom that the liberal metropolis had embraced after the war.

The Elizabeth Short, or “Black Dahlia,” crime scene in January 1947.

(Los Angeles Times)

This image, of a young woman with dreams, goals and a few foibles, is what historian William J. Mann sketches in his sensitive new book, “Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood.” The bestselling author of “Tinseltown” and “Bogie & Bacall” arrives with a meticulous and thorough retelling — five years in the making — that resists the sensationalism of the infamous crime to restore dignity back to this young woman’s image.

Short’s personality and complexity, attributes long discarded as her life became bastardized, stand in stark contrast to the inhumanity of her death. On Jan. 15, 1947, Short’s naked body was discovered in a vacant lot in Leimert Park severed in half, drained entirely of blood and posed for the public to find. Deep cuts were made to her breasts and torso while a perverse ear-to-ear “Glasgow smile” was sliced across her cheeks.

After almost 80 years, the unsolved murder now remains part of the city’s lore. A metaphor of L.A.’s past immortality and exploitation after World War II, the crime has fascinated novelists, filmmakers and countless true crime writers. James Ellroy stresses Short’s promiscuity against the city’s moral decay in his 1987 novel, “The Black Dahlia,” while many others painted her as a femme fatale in their salacious attempts to solve her murder.

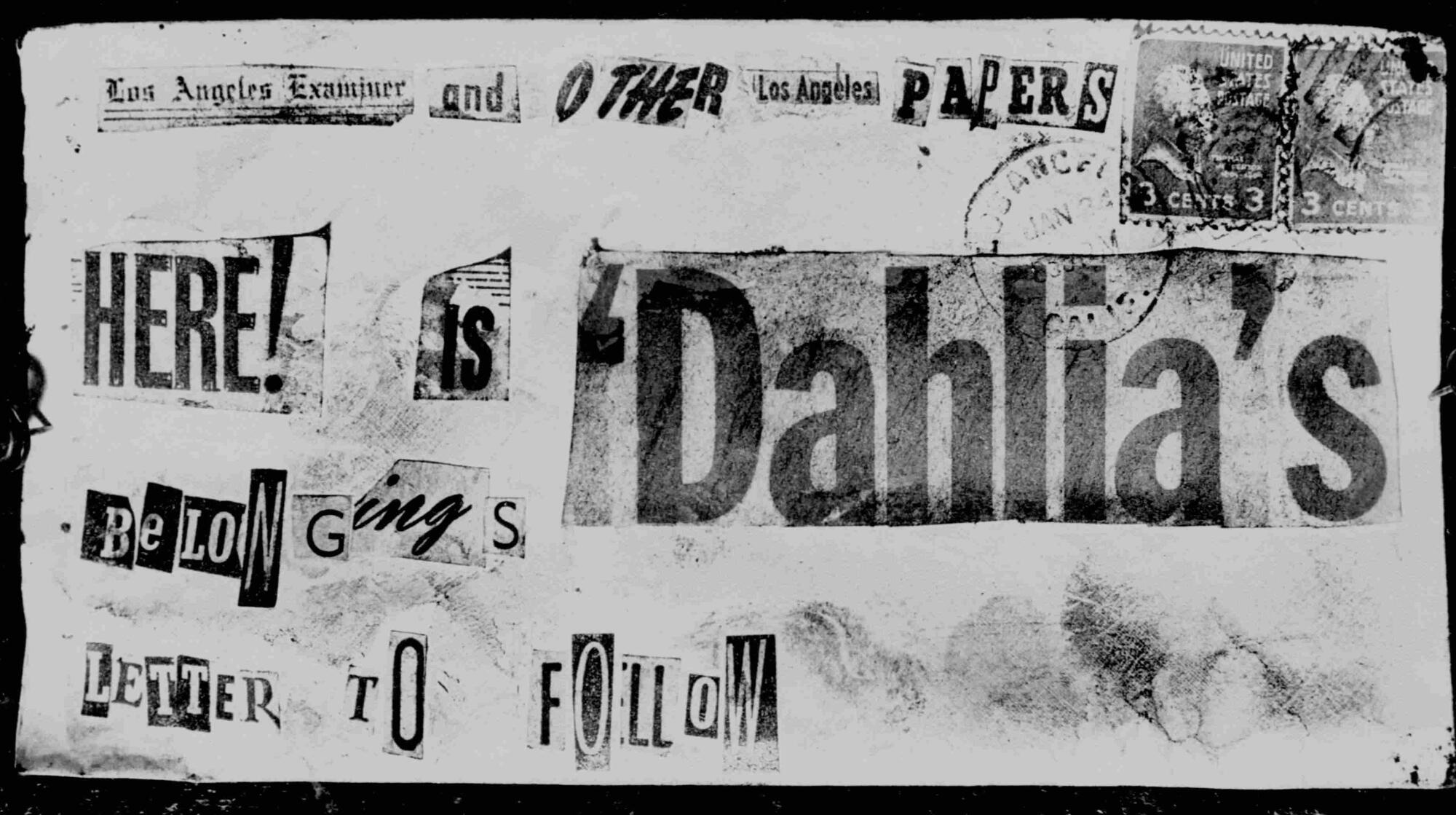

This envelope, containing the birth certificate, address book and personal papers of 22–year–old Elizabeth Short, was received at the L.A. post office on Jan. 24,1947, and turned over to police .

(Associated Press)

Taking either path never appealed to Mann, who was determined to deliver justice to Short in his compassionate chronicle of her brief life. “Until now, they’ve all been focused on the killer,” Mann says over Zoom. “Eighty years later, and we still aren’t given a picture of who this young woman was.”

Short’s image has proven collateral damage in the long project to solve her crime. Mann was insistent, however, on breaking that vicious cycle. “Elizabeth is very, very different from ‘Black Dahlia,’ ” he says. “They’re two very separate creations. I wanted to do my best to try to figure out who may have done it, but not so much to solve the crime as to understand Elizabeth’s story.”

A series of falsehoods have persisted over time: Short was a sex worker. Short was a gangster’s moll. Short wanted to become the new Lana Turner. “Black Dahlia” reveals the truth is far more unremarkable. Short may have flirted with men but rarely practiced casual sex. There may have been some male suitors but never any who were gangsters. Movies may have been on her mind — but close friends say she never actively pursued acting.

Each fact is backed by thorough fact-checking and new archival searches. This is paired with interviews Mann had with surviving relatives and friends of those who once knew Short or investigated her murder.

Experiencing the liberties L.A. offered women after World War II — such as the ability to date different men and find ongoing employment — is what is truer to Short’s story than any talk of gangsters or sex work. “Elizabeth Short was not a proto-feminist, but she was part of that new generation that said, ‘I don’t have to stay home,’ ” Mann says.

Women who resisted marriage or monogamy faced judgment and misogyny for enjoying these new-found freedoms. One sex crime study of the time, Mann reports, even claims that “seductive” women were “participating victims” in their assaults.

Both the original news reporting and police investigation would be tainted by these sexist views.

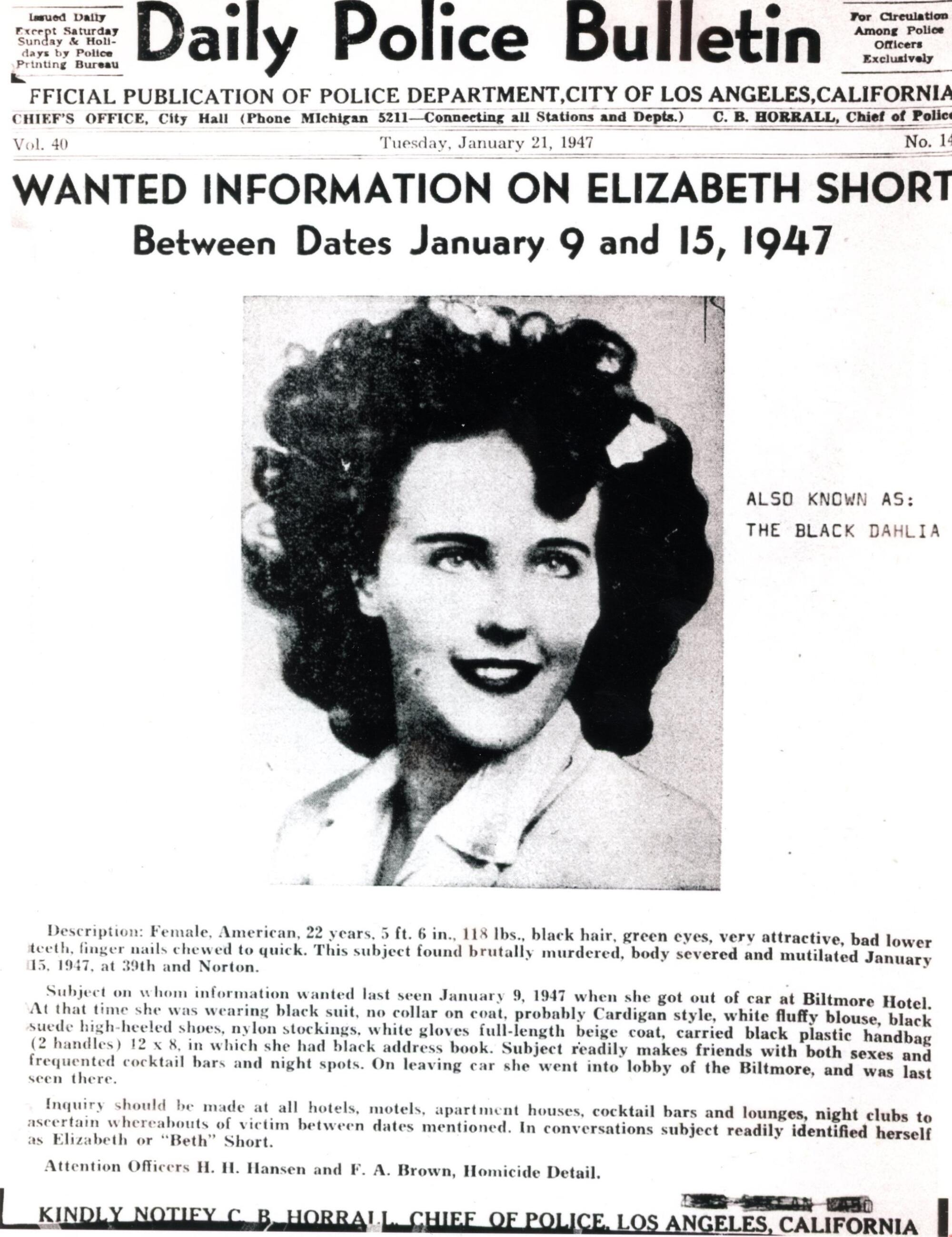

The first reports of the crime were mostly objective — one newspaper described Short as a “beauteous 22-year-old” — but these soon devolved into salacious gutter journalism. In a nod to 1946 film, “The Blue Dahlia,” the 22-year-old quickly became branded by this moniker: a sexualized seductress and flirt who wore “black lacy things” and “black sheer clothing.” (Neither was much true, Mann says.)

Decades on, the reports mostly reveal how journalists and editors exploited this tragedy to sell newspapers and trade in familiar victim-blaming. “This is just an ongoing trope in society that women are blamed for their abuse, their murders,” Mann explains. “It was painful to go through and see how Elizabeth was done … she went from this kind of innocent victim in the first reporting to this sinister, slinky woman, somehow responsible for her murder.”

The police would prove no better. The lead detective on the case, Harry Hansen, once told journalists: “Short liked to tease men. She probably just went too far this time and set some guy off into a blind, berserk rage.”

A photo of Elizabeth Short on a flyer from an original Los Angeles Police Department Police Bulletin, 1947.

(Los Angeles Times)

Restoring dignity to Short’s legacy was paramount to Mann; to solve her crime was never his aim. “It has always been the focus of all the books that have come out about Elizabeth Short. She appears in the first two scenes to get slaughtered, and then it’s about the killer,” Mann says. “I didn’t want to do that.”

The book does advance one theory of who the murderer is. Somewhat serendipitously, new independent analysis first reported in The Times by Chris Gofford has identified the same person as the likely killer. But this individual joins a crowded field of suspects other writers have also conclusively identified: from a former police detective’s late father (“Black Dahlia Avenger”) to a hotel bell-hop who co-conspired with the police (“Black Dahlia, Red Rose”).

Author William J. Mann

(Simon & Schuster)

All attempts at solving it then remain somewhat speculative as the case is an open homicide. Mann, like so many others, didn’t have access to the LAPD’s own files but to other public records and archival material. “We do have quite a bit of a record from the district attorney and those records are available,” Mann says. “I’ve become adept when I do my research into interpreting fragments.”

What “Black Dahlia” ultimately imprints on its readers is Short’s vulnerability and desperation, someone more restless than “man-crazy,” more kindhearted than “cold.”

“Elizabeth Short’s death was notorious and grisly,” Mann says. “Her life was ordinary and unremarkable. And yet her life is still more important than her death.”

One of the book’s most poignant moments comes from a letter Short penned to her fiancé, Matt Gordon, an aviator who died before the two were married. In Short’s own words, it shows a vitality and hopefulness that this 20-something woman had for her future.

“Short said in the letter, Matt, ‘I’d like to fly too,’ ” Mann says. “To me, that line really gave me an insight into her. She wanted to fly, metaphorically. She wanted to see the world. And that’s what I wanted to do too. That’s what I wanted to capture in the book.”

Smith is a books and culture writer.