On Jan. 21, 1894, Mrs. Henrietta Sechrist and her husband Jay headed out to the California Midwinter International Exposition in San Francisco. It was still a week before the fair’s official opening, but there was plenty to see. Henrietta had fallen behind her husband near the scenic railway when she felt something brush her arm and then movement in her jacket pocket. “I just turned and grabbed the hand that was coming out of the pocket with my purse,” she later told a San Francisco Examiner journalist. “And while I hung on to the robber with one hand, I slapped him good with the other.”

Henrietta, described as a charming young woman with sparkling black eyes and dimples in her rosy cheeks, was initially mortified by her own behavior. “To think how I had stood there and struck at that poor man,” she said. “I asked my husband to let him go, but he would not do it.” Jay Sechrist held on to the failed pickpocket until officers arrived, only to learn that the man’s suspicious behavior had already caught their attention. While the police had lost sight of him earlier that day, Henrietta did better and stopped James Rogers, a notorious thief from out of state. A San Francisco Examiner reporter noted that the young woman was the only one who had caught a pickpocket that day, but officials had been trying to do the same for weeks.

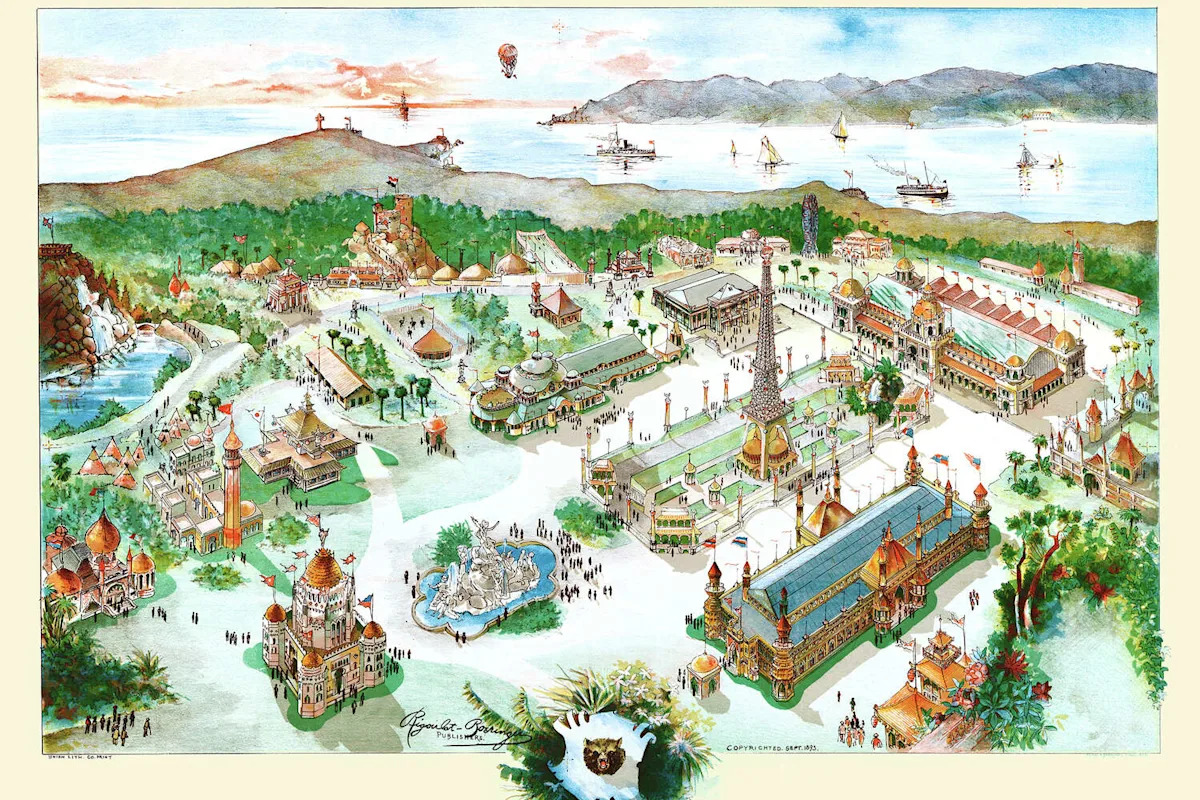

A view of the the Midwinter Exposition fairgrounds in San Francisco, 1894. (Fair Use)

A cross-country operation

Rogers’ presence in San Francisco wasn’t a surprise to local authorities. In early January 1894, Chicago public safety officers warned their San Francisco counterparts that con artists, pickpockets and others who traveled the country working the crowds were likely headed to their city’s exposition. Michael H. de Young, owner of the San Francisco Chronicle, had spearheaded the event hoping to show off San Francisco’s mild winter climate and counter an economic slump sparked by the national depression. Though the Stockton Evening Mail newspaper mocked the exposition as a “midwinter fake” and “weak and puerile imitation” of Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair, the Bay Area event would feature exhibits from more than 30 countries and was expected to draw millions of people over its nearly six-month run. Chicago’s officials had tried, but often failed, to protect their exposition visitors from crime. San Francisco officials were determined to do better.

In the weeks leading up to the fair, newspapers up and down the West Coast noted an influx of Eastern crooks. San Francisco’s police chief, Patrick Crowley, dismissed his city’s early arrivals as mostly petty criminals with a “penchant for overcoats, canes, umbrellas.” Officials began charging suspected thieves with vagrancy and threatened a six-month jail sentence if they didn’t leave San Francisco immediately. By Jan. 7, over 100 suspected criminals had been arrested and photographed before they boarded the eastbound train with a promise never to return.

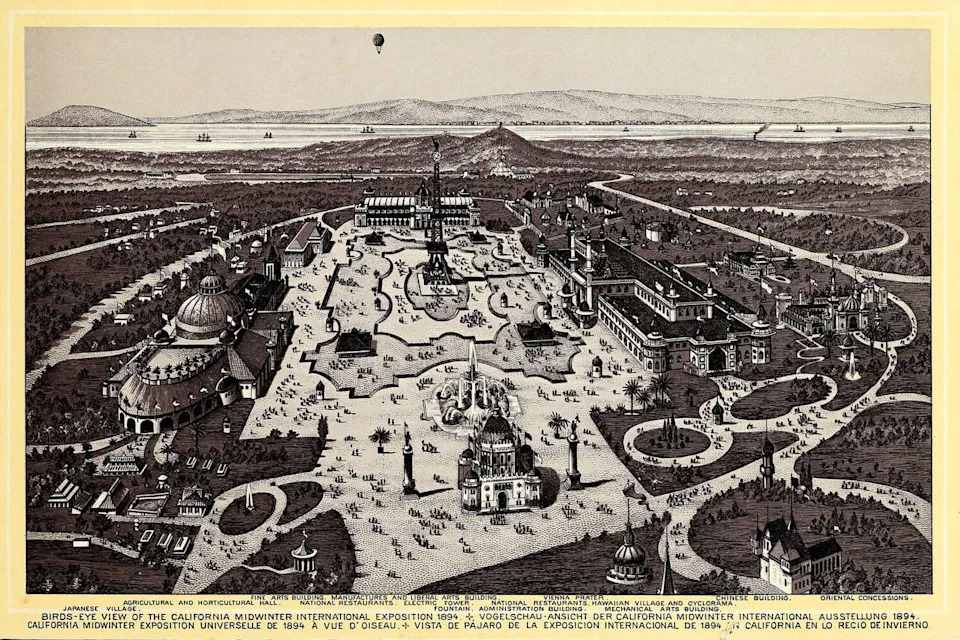

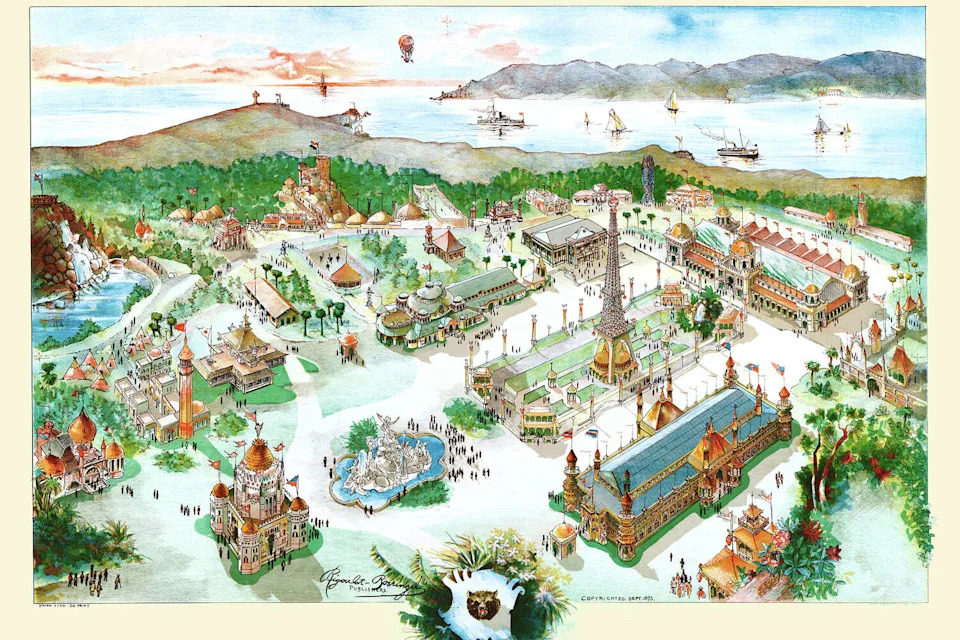

A bird’s-eye view of the California Midwinter International Exposition, 1894. (Fair Use)

Crowley hoped his aggressive approach would deter at least some of the country’s big-time crooks – and that experienced Chicago detectives who’d offered their services would help him catch those who came anyway. And they were coming. Police departments sent word when “known rascals” left their city heading west. Three men caught robbing a grocery store in Denver, Colorado, had tickets to San Francisco in their pockets; others arrested in Pueblo had the same.

BEST OF SFGATE

Central Coast | ‘Doomsday fish’: Once-in-a-lifetime sea creature encountered in Monterey Bay

Technology| A Calif. teen trusted ChatGPT for drug advice. He died from an overdose.

Central Coast| He gifted Calif. one of its largest city parks. Then he shot his wife.

Culture | Tragedy cut Sublime’s fame short. Now the singer’s son has the mic.

Get SFGATE’s top stories sent to your inbox by signing up for The Daily newsletter here.

On Jan. 21, 1894, the San Francisco Examiner warned that “a great army” of pickpockets, flim-flam artists, sandbaggers and more who had “escaped the clutches of the Chicago police” during the 1893 World’s Fair were on their way to the City by the Bay. Among them, an old Chicago detective interviewed for the story warned, was sneak thief John Cook (aka “Glass-Eyed Johnny”), smooth-talking diamond nipper “Frenchy” McNichols, and Charles (Cincinnati) Red Hyle. Hyle was a hotel thief whose ability to rapidly grow a beard into a “cockney style with long flowing side whiskers,” as author Thomas F. Byrnes wrote, fashion a simple mustache or change his look completely with a clean shave made him especially hard to catch.

The story also warned against “diamond-decked female highway robbers.” These beautiful women drew unsuspecting, often intoxicated men into dark alleys, saloon back rooms and private quarters – and officials knew men seldom reported it when they were then robbed by a seductress. Many of these crooks intentionally targeted married men for that reason. Officials believed that Minnie May, deemed the “wickedest woman in Chicago,” and rumored to have made over $20,000 in 1893, was also coming to San Francisco.

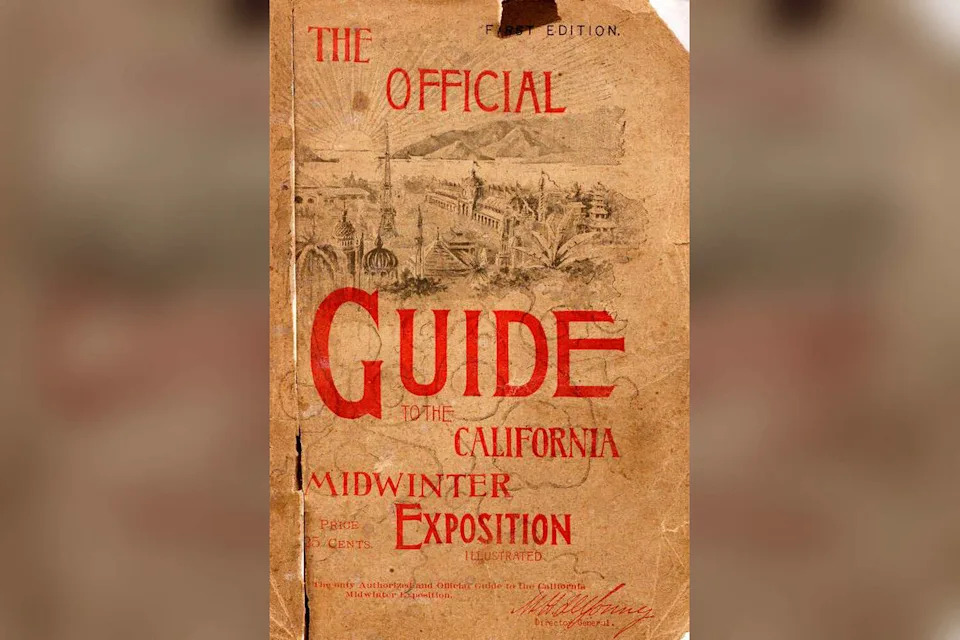

The visitors’ guide to the 1894 California Midwinter Exposition. (Fair Use)

The San Francisco Examiner article advised residents and visitors to secure wallets and purses and refrain from flashing money and jewels. It also warned against judging strangers strictly by their clothing and emphatically reminded readers that “people who are just as smart as you are have been robbed.” Travelers were also encouraged to use the newly developed system of “checks” instead of carrying large amounts of cash, though officials would soon lament that too many merchants and lodging house managers had taken bad checks on faith.

Crooks arrived alone, in pairs and in small gangs all through early January. Some lay low as they waited for larger crowds to arrive with the official grand opening of the fair. Others worked the Bay District racetrack. The San Francisco Examiner had dubbed it a “pickpockets paradise” after track officials stopped admitting officers for free and they declined to pay “for the privilege of hunting for pickpockets.”

Opening day

On Jan. 27, over 72,000 people passed through the turnstiles and entered the Midwinter Exposition. An additional 4,500 entered as part of the parade, and an estimated 10,000 came in over the fences without paying. Those who had never been out of the city, and perhaps never would, could wander through an Egyptian market, a Turkish village and a Moorish mystic maze. They could see exotic animals perform tricks. Adults paid fifty cents to get in, children over 6 cost a quarter, and those under 6 got in free. Special attractions and food cost extra, which meant that many guests were carrying cash.

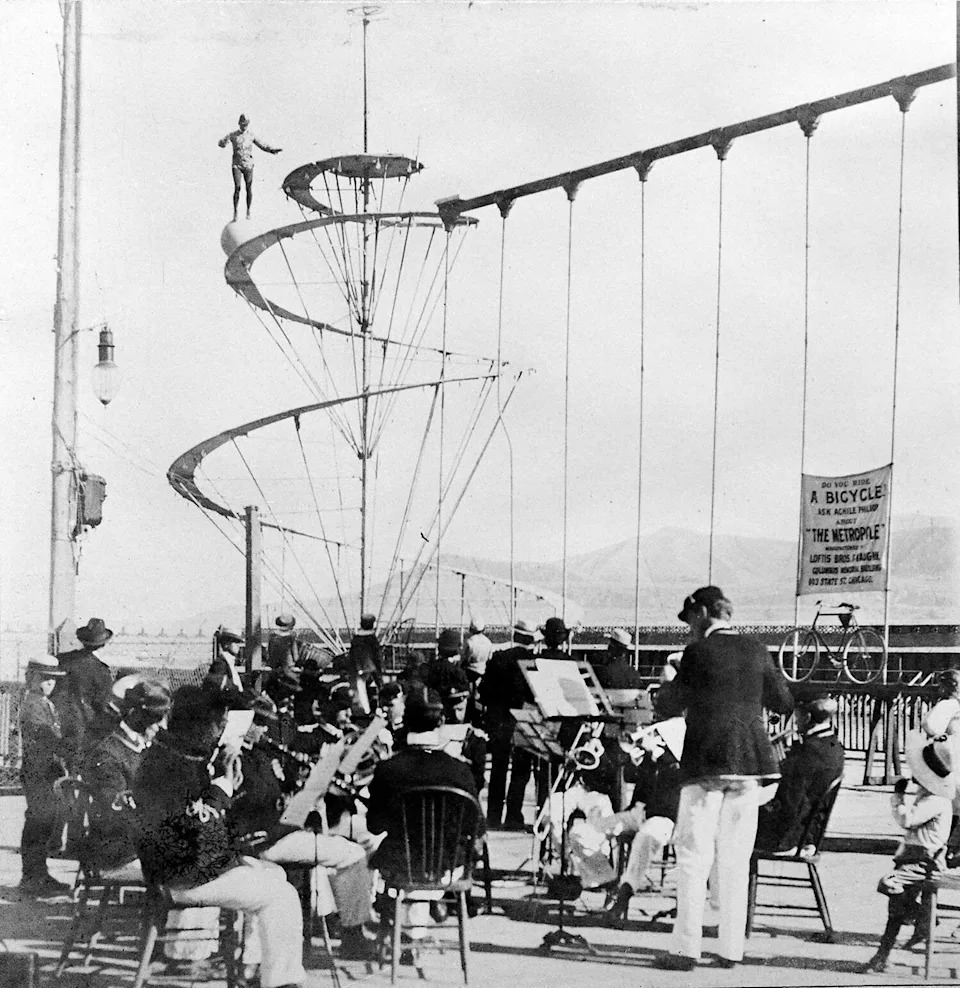

French circus performer Achille Philion balancing on a ball atop a spiral tower at the California Midwinter International Exposition in San Francisco in 1894. (Graphic House/Getty Images)

Police Capt. Isaiah Lees and 16 officers patrolled the grounds that day and caught around a dozen pickpockets robbing visitors. Short, stout, middle-aged Emma Taylor, 15-year-old John Lovell and San Franciscan John Pickett were among them. Taylor was known as the “woman in black” because she often dressed in mourning black and picked pockets at funerals. Lovell was a “pocket dipper” well known in St. Paul, Minnesota, and Pickett was rumored to have made $8,000 during the Chicago World’s Fair.

Many of the thieves were released on bail with the understanding they could (and should) leave town. Others were held for a time as officials debated their fate. On Feb. 23, three of those arrested on the opening day of the fair, including 15-year-old Lovell, were finally released after they agreed to board a steamer and leave California. Others did not get off so easily. Charles Norton [aka Morton] was spotted stealing a purse on opening day. He threw it and ran but was stopped with the help of fairgoers and charged with grand larceny.

Others, like Richard Preston, never reached the fair. Windy Dick, as he was also known, was wearing an elegant fur-lined overcoat with holes in the pockets to aid his pickpocketing when he was arrested in Oakland. His exceptionally large nose apparently gave him away. Authorities took his picture and released him for 24 hours, suggesting he head east. He did. On Feb. 5, the New Orleans Times Democrat noted that many notorious outlaws were coming to the Crescent City for carnival season. Windy Dick, Red Hyle and others who had been expected in San Francisco were among them.

Other targets

Enhanced surveillance at the expo simply redirected many Eastern crooks, who remained determined to profit from their long trip to San Francisco. Some worked the racetrack until newly hired Pinkerton detectives drove them out. Others worked the streetcars and ferry terminals. Some of the most intelligent and sophisticated pickpockets went stylishly dressed to the best hotels, lingered in the lobby and struck up friendly conversations. Well-heeled guests only realized later, when they missed their wallets or watches, that they’d been talking to a thief.

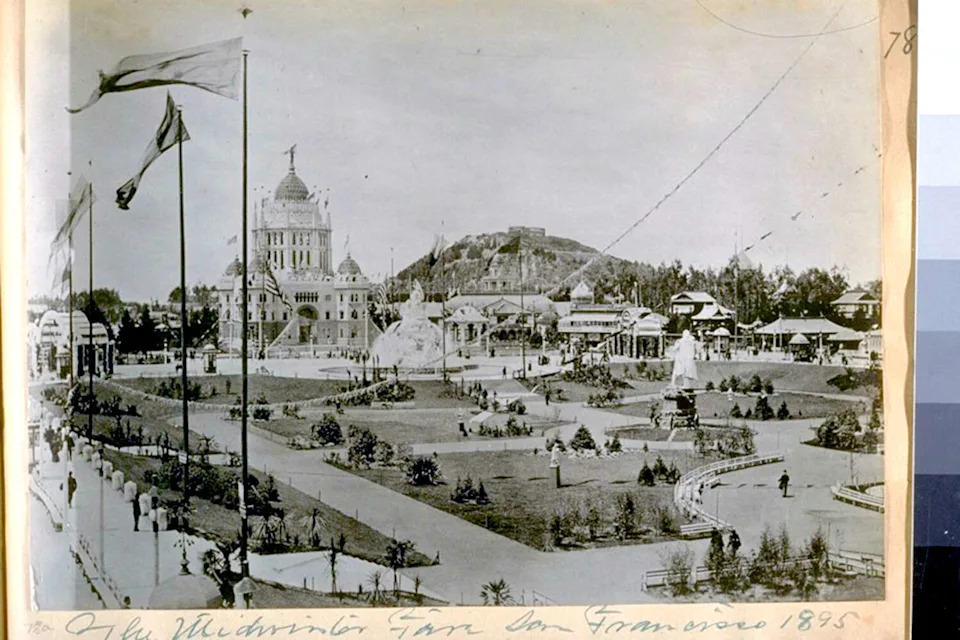

The California Midwinter Exposition, 1894. (Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Counterfeiters passed fake bills and got legitimate change in return. Others used forged letters of credit to pass bad checks. Burglars watched families pack up for a day at the fair and then broke into their homes and robbed them of valuables. A structure fire on Market Street drew pickpockets who robbed distracted gawkers. Con artists ran fixed card games, knowing most victims were too embarrassed by their own gullibility to report them.

At the end of February, exposition administrators hired 14 “secret service” men to help catch those continuing to target the event. Five more were hired to ensure the fair was getting its percentage of concession receipts and to stop the steady stream of thefts. That December, a number of Turkish rugs believed to have been stolen at the fair were found with one of San Francisco’s most notorious fences.

Other officials also remained vigilant. In mid-March, the San Francisco Morning Call announced that a Chicago detective had “happened to saunter into the racetrack” the day prior and immediately spotted a known pickpocket and three confederates. After being threatened with arrest, the four boarded the train east that night, and police Chief Patrick Crowley crowed that the crooks had been in the city for only seven hours.

Others, however, resisted the eviction. Officials painted pickpocket Adam Stroh as a criminal mastermind, but at heart, he was just a hometown thief. In mid-March, he pleaded guilty to vagrancy but was granted a suspended sentence on the promise that he would leave the city immediately. He promised – but stayed. Stroh had grown up in San Francisco, and his widowed mother and siblings still lived in the area. In May, San Francisco officers caught him breaking into a house. That September, he was convicted of burglary and sentenced to 2.5 years in Folsom State Prison.

A bird’s-eye view of the California Midwinter International Exposition. (Buyenlarge via Getty Images)

Crowley’s policy of pushing criminals out of San Francisco saved him headaches and Bay Area taxpayers the expense of multiple trials, but other communities paid the price. Oakland was haunted by pickpockets working the ferry dock – and Eastern thieves who wandered the city lifting everything from churchgoers’ jackets to diamond rings. Los Angeles officials told residents to remain on guard for Eastern crooks who were certain to stop in Southern California on their way to or from San Francisco.

A job well done

Officials’ hard work paid off, but one of the most notable criminal captures during San Francisco’s Midwinter Fair remained the one by Mrs. Henrietta Sechrist, the charming young woman who had caught James Rogers’ hand in her pocket. “Oh, it was nothing,” she told journalists who found her at home the night of her adventure. “I was not scared in the least. I suppose some women would have screamed or fainted, but it didn’t come natural for me to do either.”

When reporters later asked Rogers how he felt about being captured by a woman, he “assumed an air of injured innocence” from his jail cell and insisted he was only enjoying the fair’s attractions when someone thrust Henrietta’s purse into his hands. “I was so surprised that I just stood there,” he said. “And this woman slapped my face three times and shouted: ‘You miserable puppy, you stole my purse.'”

James Rogers was among a handful of Eastern crooks convicted of grand larceny that spring. On Feb. 24, 1894, he was sentenced to three years in San Quentin.

More Local

– San Francisco coyote swims to Alcatraz for first time ever

– New Bay Area city of 400,000 could be built ‘non-stop’ for 40 years

– A Bay Area mansion once hosted dignitaries. It’s now a Grocery Outlet.

– As a Bay Area highway landmark decays, new owners take over property

Get SFGATE’s top stories sent to your inbox by signing up for The Daily newsletter here.

This article originally published at When all of SF was a mark for a traveling band of pickpockets.