For five years now, Oakland has struggled with immense budget deficits. The city’s most recent financial forecast shows budget gaps hovering around $120 million each year until 2030, forcing major cuts to spending unless the city finds new revenues.

One major source of overspending in the city is the police department. By far the most expensive city service, the Oakland Police Department’s $386 million budget this year is about 19% of Oakland’s total spending. And each year, OPD has come under scrutiny for its runaway overtime spending, routinely blowing past its approved levels by millions of dollars. Last fiscal year, the Department spent over $55 million on overtime. Thirty-one million of this was over budget.

According to Huy Nguyen, president of the Oakland Police Officers Association — the city’s police union — OPD’s ongoing staffing shortage is driving overtime.

“At this staffing level, more officers will be forced to work excessive overtime, which in turn will accelerate attrition,” Nguyen said in a statement. “We cannot meet the needs of our community without forcing officers into more shifts.”

It is true that OPD is severely understaffed by hundreds of officers. Mayor Barbara Lee is attempting to shrink the staffing gap, with plans to increase the number of officers.

But historical data throws into question whether increasing staffing will rectify OPD’s chronic overtime overspending. A recent report by several civilian city unions found that over the past 15 years, even when department staffing increased, overtime continued to go up. From 2011 to 2024, staffing increased by nearly 9%. Over the same period, overtime went up by almost 200%.

Recent financial pressures have caused the city to lay off scores of civilian employees and freeze spending across a range of programs. Meanwhile, the number of police officers bringing in six-figure overtime packages rose dramatically.

In 2021, 58 officers were paid over $100,000 in overtime, which is generally about 1.5 times their base salary, per the police union’s contract with the city. By the end of 2024, the number of officers paid this much for overtime nearly tripled to 169.

And the number of officers making over $200,000 in overtime more than quadrupled from six to a total of 27 over the same period.

One officer’s earnings illustrate just how lucrative overtime can be for some OPD employees.

Lieutenant Timothy Dolan, a 26-year veteran who leads the traffic unit and serves as vice president of the OPOA police union, was paid $493,247 in overtime in 2024. Combined with his salary and other pay, this netted him a $711,000 paycheck, making him OPD’s highest-paid employee — a title he’s held for several years now. His pay was almost double that of the chief of police and nearly three times the mayor’s paycheck. His total compensation, including pension and healthcare benefits, was $879,000.

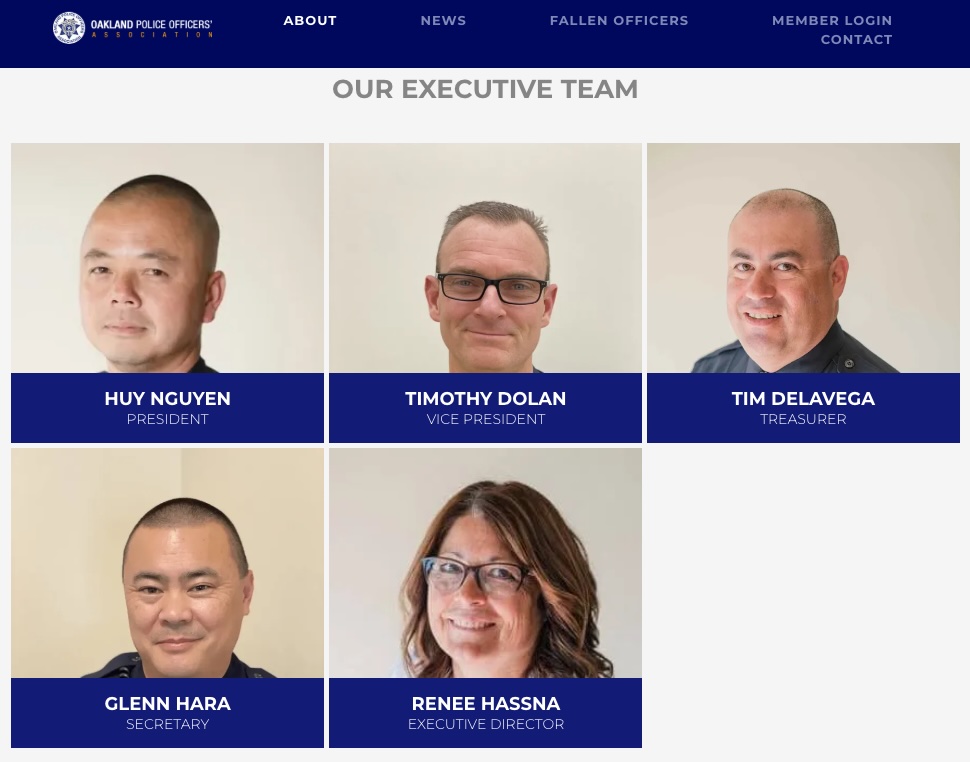

Some of the OPD officers who earned the highest in overtime in 2024 are also leaders in the city’s police union. OPOA President Huy Nguyen was paid $256,000 for overtime, putting his total pay at $473,000. Credit: Screenshot courtesy of opoa.org

Some of the OPD officers who earned the highest in overtime in 2024 are also leaders in the city’s police union. OPOA President Huy Nguyen was paid $256,000 for overtime, putting his total pay at $473,000. Credit: Screenshot courtesy of opoa.org

Dolan’s pay package raises questions about how OPD documents and approves overtime, and about whether the department is spending this money wisely.

In Dolan’s case, he earned at least $100,000 in overtime — and possibly far more — solely by reviewing paperwork for traffic collisions, records reveal.

The paperwork for Dolan’s overtime also reveals that OPD failed to document almost half of the overtime hours he worked, making it impossible to determine what he was doing much of the time.

Dolan spent over 800 hours of overtime in 2024 reviewing collision reports — the equivalent of about five months of work in a normal full-time job. This was particularly expensive for the city because Dolan, due to his rank, is near the top of OPD’s salary scale. Spreading out the work among other officers during normal shift times could have been cheaper.

“It’s an example of continued poor leadership and utilization of resources on the part of the Oakland Police Department,” said Cat Brooks, founder of the Anti Police-Terror Project, an Oakland-based nonprofit. “There’s no explanation or justification for why this particular officer would be doing that, making that kind of money.”

OPD spokesperson Paul Chambers said in recent emails that Dolan is the agency’s “subject-matter expert on collisions.” He leads the department’s traffic team, but has continued to review the reports due to low staffing.

Asked about the massive amount of overtime he logged in 2024, Dolan justified his work, saying it’s a service to the city that can generate revenue, and that the overtime hours are necessary because of OPD’s understaffing.

“Reviewing and submitting the collision reports is a service we provide to the people we serve,” said Dolan in a statement. “Finalizing reports in a timely manner will help resolve service complaints, as we have previously been backlogged in our reviews due to staffing constraints.”

Chambers, too, said the department has been working to clear its backlog of collision reports, a task it had not completed as of November.

City records also raise questions about the hours many OPD officers are logging.

We asked OPD to provide us with all of the documentation necessary to track Dolan’s overtime hours worked in 2024. This included his timecard, which shows the overtime hours he billed during each two-week pay period.

We also requested copies of Dolan’s “overtime worked forms,” which are documents that officers are required to fill out whenever they work overtime. The forms describe in detail the dates and hours Dolan worked, as well as the specific activities he spent his time on.

In Dolan’s case, the paperwork describes an officer who worked numerous consecutive and lengthy days to the extent that fatigue and safety could have become issues.

“I don’t have a problem with [reviewing collision reports] on overtime, assuming the overtime is not absurd,” said former City Administrator Dan Lindheim, who teaches public policy at UC Berkeley. “But then the question is, when it gets to be elevated hours of overtime, then how does that affect the performance of the officer during the regular shift?”

23-hour workdays, working 19 days in a row, and other astonishing schedules

In 2024, Dolan logged an eye-popping amount of overtime — 3,304 hours, records reveal. This was on top of the 1,938 hours he worked as part of his normal shifts, for a total of 5,242 hours. That’s the equivalent of more than two and a half full-time jobs.

Some work stretches were seemingly superhuman, according to the records OPD provided us.

On July 9, Dolan reported he worked 23 hours. The next day, he worked 16 hours, and for the following three days, he worked 15 hours each.

“It strains credulity,” said Lindheim. “Ultimately, I don’t think there are enough hours in the day to bill this much overtime…. It doesn’t seem to pass the laugh test.”

After providing us with an emailed statement for this story, Dolan did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. We sent him and OPD spokesperson Paul Chambers a list of questions and provided the findings from this story, including the numbers we pulled from his overtime documents; they did not respond.

Dolan’s overtime records raise concerns about how he, or any officer, can safely and effectively do their job without taking time to rest; he didn’t respond to questions about that.

“Truck drivers are only allowed to drive so many hours in a day for safety reasons,” said Julian Ware, vice president for IFPTE Local 21, a union that represents civilian city employees and which has been critical of OPD’s use of overtime. “I don’t think it should be any different for sworn officers who are carrying guns, tasers, and pepper spray, and driving vehicles. It’s a tremendous amount of responsibility that they have.”

“There’s so much research and data just in general about sleep deprivation and safety,” said Brooks. “It also impacts your irritability, your mood, mood swings.… How are you treating Oaklanders that you come in contact with? There’s no way that you’re having capable or competent judgment.”

OPD’s overtime policy says that due to the city’s budget problems and concerns about officers’ wellness, “overtime worked must be minimized, controlled, and used only as absolutely necessary.” The policy mostly describes the rules that apply to overtime when officers are required to work extra hours by their supervisors.

The policy also says officers are supposed to take at least one full day off each week. However, the city auditor’s office has identified thousands of violations of the policy in past years.

Dolan routinely exceeded this limitation, public records reveal. In one stretch, according to his Overtime Worked Forms, he worked at least 19 days in a row — and Dolan worked 15 hours or more on all but two of these days. The department didn’t respond to questions about whether Dolan was authorized to do this.

Hundreds of OT hours spent reviewing collision reports

Although more than a dozen OPD officers are trained and authorized to review collision reports, Dolan is one of only two who actually handle most of the reviews, according to Chambers.

Dolan spent at least 815 hours reviewing the reports in 2024. From the available records, Dolan spent hundreds of hours more reviewing collision reports than completing any other overtime task.

Chambers did not respond to questions clarifying whether any officers other than Dolan are authorized to use overtime to review the reports.

Dolan’s rank makes his overtime particularly expensive. Dolan served as a Sergeant in 2024, giving him a base salary of about $163,000 — near the top of OPD’s salary scale.

He declined to provide information on who, if anyone, authorized the department to use so much of Dolan’s overtime to attempt to clear the backlog of collision reports.

When asked whether spending so much on overtime to clear the backlog of reports was the best use of department resources, Chambers declined to comment and told The Oaklandside he would no longer respond to any of our questions.

Traffic collision reports have notable uses beyond law enforcement. They can generate some revenue for the city — the reports cost $25 to purchase. But only stakeholders in the collision, like people involved or insurance providers, can purchase them.

Once completed, the reports can be used to aid engineers in roadway design. They are also sometimes used by insurance companies to determine payouts. But in California, collision reports are typically not admissible as evidence in court — at least when attempting to determine fault for a collision.

Reviewing collision reports took up at least 815 hours of Dolan’s overtime shifts in 2024. Credit: Adahlia Cole/Berkeleyside

Reviewing collision reports took up at least 815 hours of Dolan’s overtime shifts in 2024. Credit: Adahlia Cole/Berkeleyside

According to Chambers and the California Highway Patrol, when a reviewing officer (like Dolan) first looks over a collision report, they will typically flag areas in need of revision and send the it back to the reporting officer with notes. Then the report needs to be reviewed again. Revisions and corrections mostly have to do with vehicle codes and the CHP’s specific style, rather than the facts of the collision.

While some collision reports are escalated to the status of an investigation, this is only in cases involving serious injury, death, or suspected crimes like DUIs or hit-and-runs.

In his statement, Dolan said Oakland averages about 20 to 25 collisions each day; it is unclear how many of those collisions are serious enough to require an investigation. Chambers also declined to provide details on how many of the reports in the backlog are serious enough to warrant investigation.

Antiquated, paper-based record-keeping makes tracking officers’ overtime impossible

Although Dolan’s timecard shows his total logged overtime hours, documentation of what he did during many of these hours remains elusive. The Department was only able to locate overtime records explaining the work he did on these shifts for slightly over half the overtime hours he was paid for in 2024.

The limited documentation they provided details exact dates and times worked and duties performed. With so many missing records, it is impossible to independently verify the accuracy of the timecards.

The Department has a history of failing to produce overtime documentation. For example, in 2017, when the police department’s Office of Inspector General requested records for 10 officers, the department could only produce about a quarter of the overtime forms requested.

Dolan’s records reflect a similar pattern. His busiest pay period — a two-week stretch when he was paid for a total of 237 hours of work, most of which was overtime — has no documentation at all beyond his timecard. When we asked OPD about the missing records, the department told us they provided us with everything they had.

Nine other pay periods are also missing documentation, including Dolan’s second and third busiest periods.

Still, the documents the department provided us show that Dolan regularly spent five or more hours reviewing collision reports, both on his days off and after working a regular shift.

This year, Chambers said, Dolan was promoted to Lieutenant. This increased his salary by over $25,000, making his overtime even more costly. Dolan continues to review collision reports due to a backlog of cases, Chambers said.

The department spokesperson said, “The hope is to be nearly caught up [on collision reports] by the end of [2025,] which, in theory, would end the overtime needed to review them.”

As of Nov. 20, Chambers said more than 275 reports were completed but needed to be reviewed, and another 500 were not yet finished.

There have been pushes to modernize the department’s overtime tracking — last year, the department reported to the auditor’s office and City Council that it would be implementing a new digitized scheduling system. But just as the first phase of the new system was slated to be implemented, the plan was abandoned due to contractual issues.

Neither city nor department spokespeople provided an explanation on why the plan was scrapped, and when asked, Chambers said that “there are no additional details being released.”

In June, the department reported once again that it plans to digitize its scheduling system — but the estimated completion date for this is nearly two years away. In the meantime, with inadequate tracking, the department claims it cannot follow its own policies surrounding voluntary overtime, according to the city auditor’s most recent recommendations follow-up report.

“*” indicates required fields