Yes, this is a thing that could have happened.

Yes, this is a thing that could have happened.

Well, it’s Friday before the Super Bowl, and we’ve nearly made it all the way through the two-week wait between the NFL’s Conference Championships and the Big Game. The Seattle Seahawks and New England Patriots have both settled into the Bay Area and are making their final preparations, and Seattle has remained a remarkably stable 69 percent favorite in prediction markets like Polymarket for the majority of the lead-up to Sunday’s contest:

I already wrote about the odds around the game, the roster changes that reshaped the Patriots and Seahawks since the last time they faced on this stage, and the general keys to the game. But before we finally get to kickoff, there’s still time for one last sweep through the notebook — the odd historical connections, quirks and details that don’t quite fit anywhere else, but still help frame the Super Bowl and how we got here.

In going through the historical connections between the Patriots and Seahawks, obviously Super Bowl XLIX tops the list — not only was it Part I of what is now a multi-time Super Bowl rivalry, but it was also one of the wildest Super Bowls of all-time. The way it ended is something that will overshadow every other angle between these teams, including possibly Sunday’s game if it doesn’t offer its own crazy thrills.

But another weird connection between the teams is just how close both came to not actually being themselves anymore, during a pair of ownership crises in the early-to-mid-1990s.

The ‘90s were a time of rampant franchise free-agency, as owners began seeking more and more benefits from local governments — in the form of tax breaks, sweetheart stadium deals and other public subsidies — or else they’d threaten to pack up the team and take it to a place whose city council would give them what they wanted. From 1993-1997, eight different “Big Four” major pro teams swapped cities, including four from the NFL alone (both L.A. teams, the Rams and Raiders, plus the Cleveland Browns and Houston Oilers):

Against that backdrop, the New England Patriots were owned in the early ‘90s by James Busch Orthwein, who’d bought the team from Victor Kiam amidst a bankruptcy crisis. Orthwein was the great-grandson of Anheuser-Busch founder Adolphus Busch, whose family was synonymous with St. Louis — and, later, St. Louis sports teams (such as the Cardinals). With the Pats struggling both on the field and financially, and St. Louis having lost the football Cardinals in 1988, it suddenly became very possible that New England would lose its NFL team in 1993.

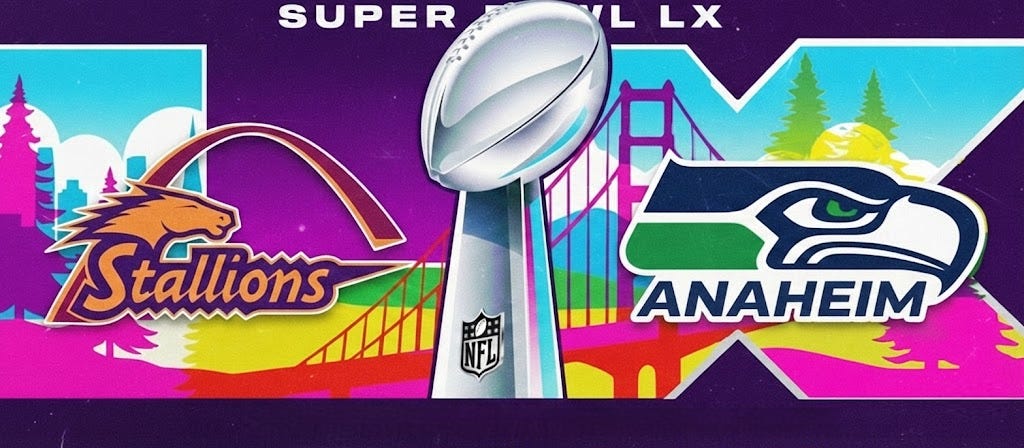

Plans and designs were even drawn up for the Patriots to become the St. Louis Stallions, clad in purple and gold uniforms. As Orthwein prepared to uproot the team, only one person stood in his way: Boston-born paper tycoon (and longtime Patriots fan) Robert Kraft.

As part of Kiam’s asset liquidations in bankruptcy court, Kraft had acquired the lease to Foxboro Stadium, which ran through 2001. Though he’d lost his bid to buy the team as well, Kraft did have the ability to force the team’s owner to honor the lease agreement — or face legal consequences. When Orthwein attempted to buy out Kraft’s stadium lease, Kraft turned it down; he also made clear that he would take any other owner to court if they tried to move the team out of Foxborough. Ultimately, Orthwein had no choice but to sell the Patriots to Kraft in 1994.

Around the same time, Seahawks owner Ken Behring was hatching his own relocation plans. Behring had bought the team from the Nordstrom family — of the eponymous department store — in 1988 with business partner Ken Hofmann. But after facing mounting losses both on and off the field, and denied by the city the payments for improvements he was seeking to the Kingdome, Behring ordered moving trucks to show up one Sunday morning in February and begin shifting the team’s operations down to Anaheim, CA:

“It is with great regret,” Behring said, “that I am announcing today that the NFL franchise we purchased in 1988 is leaving Seattle.”

The public outcry was great, the players were confused and the league itself was irate. Behring hadn’t filed the right paperwork to apply for a move, resulting in daily fines as long as the team was being run out of Anaheim. But for a decent portion of the 1996 offseason, the Seahawks’ players and staff worked out of makeshift facilities in Southern California that used to belong to the since-departed Rams.

“It was difficult, to say the least,” said Dennis Erickson, who was Seahawks head coach at the time.

Eventually, Behring had to back down for the same reason Orthwein did in New England — he was legally locked into a stadium lease (in Seattle’s case, at the Kingdome through 2005). In the aftermath of the botched relocation, Behring quickly sold the team to Seattle-born Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen for $200 million, and Allen worked with local lawmakers to secure funding for a new stadium as a condition of the sale.

For all their wealth, both Kraft and Allen were also examples of local businessmen who genuinely loved their football teams and stepped into ownership crises that nearly saw the Patriots and Seahawks pack up and leave town. It’s fair to say that, in each case, they helped save the franchise and paved the way for championship success down the line — potentially including this weekend. Or otherwise, as silly as it sounds, we might staring at a matchup between the St. Louis Stallions and Anaheim Seahawks on Sunday instead of New England versus Seattle.

One of the big storylines going into the game has been the Patriots’ strength of schedule (or lack thereof). Along their regular-season road to the Super Bowl, the Pats faced only four teams who made the playoffs, and only three teams with a winning record. (They faced just a single winning team — the Bills in October — from September 22 through December 13.)

In the playoffs, they faced better competition in the Chargers, Texans and Broncos… but even there, two of the three games were played in horrible weather conditions and the latter was also against a team with its backup QB. All told, New England had the worst Simple Rating System (SRS) schedule strength in the league by far — at -4.5 points per game; no other team was worse than the Bills at -2.3 — and they go into the Super Bowl with the fourth-lowest schedule strength of any Super Bowl-bound team since the 1970 AFL-NFL merger:

But does facing a weak schedule in and of itself make a team less likely to win once they get to the Super Bowl? We can see in the chart above that a number of the weakest SOS teams actually did end up winning the game regardless — though overall, the team with the stronger SOS metric wins the Super Bowl 60 percent of the time (33 in 55 tries) since the AFL merger.

And the effect does appear to be additive — the more mismatched the schedule strengths, the less likely the team who faced the weaker slate is to win. Just running a logistic regression for the Super Bowl off of schedule-strength alone, a team whose SOS is 1 point worse than the opponent would be expected to win 47.6 percent of the time; a team 3 points worse, 42.8 percent; and 6 points worse (like New England), 36.0 percent.

But there’s more to measuring team strength than just the schedules they faced, and what a team did against its schedule is more important in predicting its Super Bowl success than who it faced. If we expand our regression to include both components of SRS — average margin of victory and average opponent strength — a 1-standard deviation improvement in margin (holding SOS equal) boosts your odds of winning by 10.7 percentage points, while a 1-standard deviation improvement in SOS (holding margin equal) boosts your odds by just 4.6 percentage points, less than half the effect.

So yes, it does matter that the Pats faced an easier schedule than the Seahawks. But it also matters that New England won its games by 10.0 PPG, regardless of schedule strength, because a team’s margin matters more when predicting the Big Game than its SOS does. (Putting aside the fact that Seattle actually also had a higher MOV than New England, at +11.2.)

The headline matchup of the game — between Patriots quarterback Drake Maye and his Seattle counterpart Sam Darnold — is also maybe the one filled with the greatest intrigue.

On paper, Maye owns the matchup, coming off one of the most efficient passing seasons we’ve ever tracked, while Darnold has been more of a steady, above-average presence within Seattle’s broader all-around machine. To wit: Maye led all QBs this season in Expected Points Added (EPA) above replacement, while Darnold ranked a respectable-but-hardly-dominant 11th.

In terms of the gap in regular-season EPA performance (per 17 team games) between Maye and Darnold, this Super Bowl ranks 17th since the 1970 merger. It’s a far cry from Tom Brady versus Eli Manning in 2007 — which, we all know how that went anyway — but it’s fairly lopsided nonetheless. What truly makes this year’s matchup stand out, though, is something Robbie Marriage pointed out on Notes the other day: that the QB with the plainly superior stats is the underdog in the game itself.

It is certainly rare to see a QB which an edge of this magnitude in individual EPA above replacement per 17 lead a team with a less than 50 percent pregame chance in the Elo ratings. In that regard, Maye had the sixth-biggest gap in value per 17 from the regular season over his Super Bowl counterpart among pregame underdogs to win the game:

This speaks to the non-quarterback differences between the teams, which we know favor Seattle. But nonetheless, it’s interesting how much Maye’s dominant season has tended to be overlooked — he lost MVP honors to Matthew Stafford despite the superior stats — and that’s been especially true as Maye has struggled during the playoffs. Because of this, we’ve sort of forgotten how much of an edge the Patriots do have at the game’s most important position.

And if this game does swing on quarterback play, history says the edge goes to the more productive passer (again by EPA above replacement) 82 percent of the time since the merger. It’s an open question whether that will indeed be Maye — who needs to rediscover the dominant regular-season version of himself on the sport’s biggest stage — or Darnold, but the entire season suggests it’s more likely to be the former than the latter.

Finally, in the spirit of Remembering Some Guys, I’ll end my notebook-dump with a tribute — inspired by thinking of longtime Seattle QB Dave Krieg, patron saint of the Football Folly — to the best players in Seahawks and Patriots history who never won a Super Bowl with their franchise, according to Approximate Value. Whichever team wins on Sunday, this one is for them:

Filed under: NFL