In 1996, a 17-bed, state-licensed hospice began caring for dying incarcerated men at California Medical Facility in Vacaville, a city on the southwestern edge of Sacramento Valley. At that time, the hospice unit mainly took care of patients dying of AIDS. Today, many of the patients housed there are dying of cancer, the leading cause of death in U.S. prisons.

In June 2024, I visited the hospice unit on a reporting trip, along with Eddie Herena, a former staff photographer for San Quentin News at San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, a prison in the Bay Area. We were there to understand what it was like to receive a terminal diagnosis while in prison.

All of the patients at CMF had ceased treatment; the main objective of their care was comfort. Since CMF’s hospice program typically only houses patients who have six months or less to live, I expected the mood to be somber — like the kind you might encounter at an underfunded senior living facility. But what we found was something brighter and more alive.

The hospice unit more closely resembled a hospital ward than a prison. Medical staff, social workers, psychologists and a chaplain buzzed about. If I hadn’t handed over all my belongings, passed through a metal detector, and walked through a line of people dressed in state-issued blues, I might not have guessed I was in a prison at all. The walls of the unit were decorated with completed puzzles showing colorful scenes of animals and nature. There were two fish tanks and a garden full of succulents, with benches and a gazebo.

Some patients appeared vitalized to have visitors. They relished the opportunity to chat about the garden, show off their artwork or poetry, talk about their case or pose for photos. Others kept a wide berth, tolerating Eddie’s camera but intent on pacing around the garden.

One side of the unit was occupied by dorm-style rooms that used curtains to create an enclosure in each corner. Many of these small “rooms” were crammed with belongings — files, food, clothing, medical supplies and electronics encased in clear plastic.

Outside in the garden, a patient received a haircut from a care worker. Doctors and other staff members stopped by to check on patients, and to let them know when they were headed out for the day. One nurse, clad in a yellow paper gown, told Richard Hirschfield, a man with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer, that she had saved an extra chocolate milk for him in the fridge.

Having Eddie there put most people at ease, making it easier to start conversations. Patients gave a knowing nod when he mentioned his own incarceration, and they showed interest in seeing their image appear on the small screen after Eddie clicked the shutter. A selection of his photographs can be found below.

.wp-block-quote {

border-left: 0;

}

If you or a loved one are worried about cancer, click the image to download a printable one-page resource guide. For a Spanish version, haz click aquí.

The hospice care workers, many of whom were incarcerated at CMF but housed in a different area of the prison, exuded a sense of pride — in themselves, in their work and in the unit. “A lot of us who work here are in for murder,” said Allan Krenitzky, a care worker. “This is an opportunity for us to be decent human beings.”

The incarcerated staff were gracious and kind. When we stopped to eat the sandwiches we brought for lunch, they shared hot peppers from the garden. When we joked about how spicy they were, Gerald, one of the care workers and a patron of the garden, brought ice water in a hospital jug and poured it for us.

Once a patient nears what is expected to be his last 48 to 72 hours of life, a pastoral care worker is assigned to sit vigil so that no one dies alone. A patient’s vigil is indicated by an electric candle on a pedestal outside their room. In one of those rooms, Eddie took a picture of a care worker holding a straw to the dying man’s lips.

— Carla Canning, associate editor

A view of the hospice garden from inside a vacant hospice room. Many of these windows had white shutters with adjustable slats to let the light in.

A view of the hospice garden from inside a vacant hospice room. Many of these windows had white shutters with adjustable slats to let the light in.

The prison canteen, located in the main hallway of the prison, where residents can periodically line up to purchase snacks and hygiene items, among other things.

The prison canteen, located in the main hallway of the prison, where residents can periodically line up to purchase snacks and hygiene items, among other things.

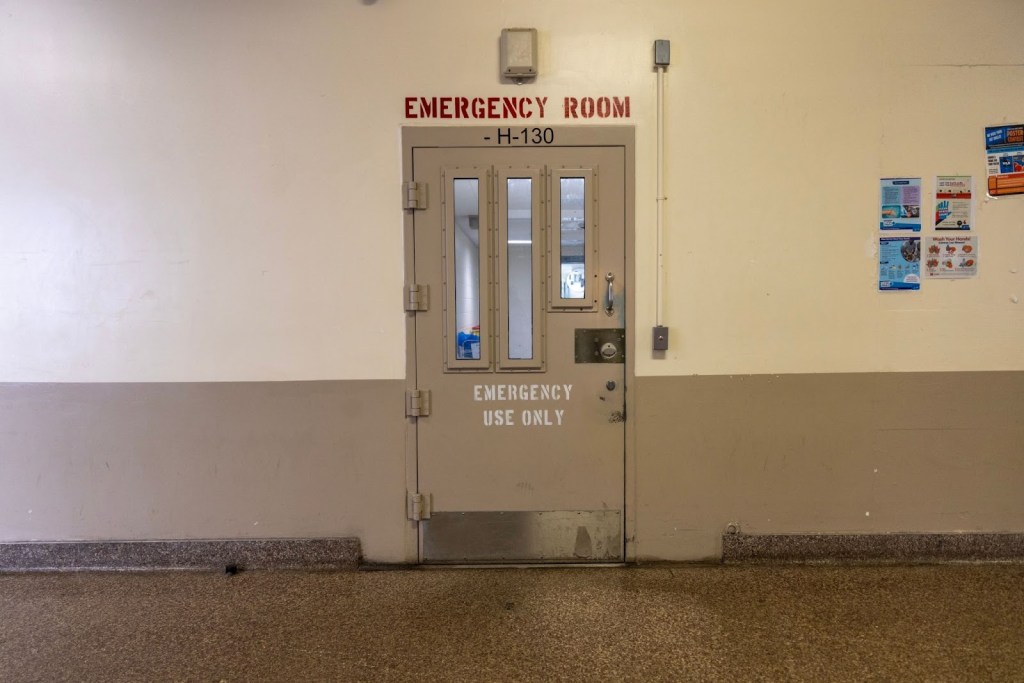

Doorways that lead to other medical wings of the prison from the main hallway.

Doorways that lead to other medical wings of the prison from the main hallway.

A hospice patient pacing around the garden path while waiting to have his hair cut by a pastoral care worker.

A hospice patient pacing around the garden path while waiting to have his hair cut by a pastoral care worker.

A cactus flower blooming in the hospice garden, surrounded by other succulents and plants. Patient Ralph Marcus said he hadn’t seen a plant up close since before his incarceration.

A cactus flower blooming in the hospice garden, surrounded by other succulents and plants. Patient Ralph Marcus said he hadn’t seen a plant up close since before his incarceration.

A hospice patient sitting in the shade in the garden.

A hospice patient sitting in the shade in the garden.

A group of pastoral care workers — residents of California Medical Facility who are trained to provide end-of-life care — pose for a photo in the garden. “A lot of us who work here are in for murder,” said Allan Krenitzky (second from left). “This is an opportunity for us to be decent human beings.”

A group of pastoral care workers — residents of California Medical Facility who are trained to provide end-of-life care — pose for a photo in the garden. “A lot of us who work here are in for murder,” said Allan Krenitzky (second from left). “This is an opportunity for us to be decent human beings.”

Care workers Michael Sullivan (above) and Brian Framstead (below) interact with hospice patients in the garden and under the gazebo.

Care workers Michael Sullivan (above) and Brian Framstead (below) interact with hospice patients in the garden and under the gazebo.

The hospice unit is complete with accessible designs, including walk-in showers for people with mobility challenges.

The hospice unit is complete with accessible designs, including walk-in showers for people with mobility challenges.

Richard Hirschfield (above, and in wheelchair below) and Ralph Marcus share a patient dorm. Each corner of the large room is cordoned off by blue-green hospital curtains to create privacy in cubicle-like rooms.

Richard Hirschfield (above, and in wheelchair below) and Ralph Marcus share a patient dorm. Each corner of the large room is cordoned off by blue-green hospital curtains to create privacy in cubicle-like rooms.

Outside a dorm, a fish tank and house plant sit atop sets of drawers containing medical supplies.

Outside a dorm, a fish tank and house plant sit atop sets of drawers containing medical supplies.

Ralph Marcus poses in a common area of the hospice for a portrait in his wheelchair. While Eddie photographed, pastoral care worker Brian Framstead (not pictured) joked about Marcus being in “a magazine shoot.” Marcus, who passed away a few months after our visit, shared his story with PJP in an extended interview, which can be read here.

Ralph Marcus poses in a common area of the hospice for a portrait in his wheelchair. While Eddie photographed, pastoral care worker Brian Framstead (not pictured) joked about Marcus being in “a magazine shoot.” Marcus, who passed away a few months after our visit, shared his story with PJP in an extended interview, which can be read here.

Ralph Marcus spent five months making this birdhouse at the suggestion of one of the unit’s doctors, who thought the craft project might take his mind off the pain he was in.

Ralph Marcus spent five months making this birdhouse at the suggestion of one of the unit’s doctors, who thought the craft project might take his mind off the pain he was in.

Pastoral care worker Alan Lama helps a patient on vigil, David Brazil, drink from a straw as he sits up in bed

Pastoral care worker Alan Lama helps a patient on vigil, David Brazil, drink from a straw as he sits up in bed

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://prisonjournalismproject.org/2026/02/11/a-look-inside-a-california-prison-hospice-unit/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://prisonjournalismproject.org”>Prison Journalism Project</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/prisonjournalismproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/cropped-PJP-favicon-2.png?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://prisonjournalismproject.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=40084″ style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://prisonjournalismproject.org/2026/02/11/a-look-inside-a-california-prison-hospice-unit/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/prisonjournalismproject.org/p.js”></script>