Piper Johnson grew up in the Richmond District, often heading to the beach to swim and surf with her family and dog, Teddy. Now a junior at Sacred Heart Cathedral Preparatory, she still loves the beach. But she saw it — and smelled it — in a different way when storms hit the city in February.

Johnson remembers a foul odor: stormwater and sewage overflow running into the sea.

“A lot of my friends who surf weren’t able to,” she recalls. “People went out and got sick because of bacteria in the water.”

Johnson had an idea, and she was in a good position to pursue it. She’s part of her high school’s four-year STEM — science, technology, engineering, and math — program that encourages students to find solutions for real-world problems.

The timing of the storms lined up perfectly with an assignment to incorporate mechanical science into a project. She decided to develop a sensor that, in real time, detects levels of dissolved solids in water, a proxy for the sewage that was making people sick. This spring, she’ll launch her prototype into local waters.

“I was like, ‘something has to happen to this,’” she said. “We can’t just continue doing this.”

Johnson’s project — hometown kid tackles a very local problem — is about as San Francisco as science gets. It’s also a great example of the spirit that the organizers of this weekend’s Bay Area Science Festival at UCSF Mission Bay want to tap into. Johnson hadn’t planned to be there, but other local kids will be.

It’s not a traditional science fair (there are no blue ribbons), although some local students will show off their projects amid a 30-foot whale skeleton, hands-on robotics, and seismology demonstrations — and perhaps even inspire the next Piper Johnson.

Small sensor, big idea

About 25 students are accepted annually to Sacred Heart’s Innovations and Inquiry (or i2) program, which spans all four high school years. Each grade level is assigned a theme: climate change for freshmen, artificial intelligence for sophomores, and data analysis to predict future trends for juniors. Seniors are asked to mentor the other grades.

Dabney Standley, director of Sacred Heart’s Innovations and Inquiry program, with Piper Johnson. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Dabney Standley, director of Sacred Heart’s Innovations and Inquiry program, with Piper Johnson. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

The issues of climate change, global conflict, and economic instability aren’t going anywhere. “These kids are the ones that we will look to, to take on these challenges,” says i2 director Dabney Standley.

Johnson said science and math have always been her best subjects, but marine life is her passion, which she also channels into an aquarium at home. She and two classmates studied declining fish and coral populations freshman year, and she knew wanted to stick with the topic even before last winter’s downpours.

After seeing friends get sick and neighbors stay indoors to avoid the stench by Ocean Beach, Johnson wanted to find a way to instantly detect whether water was safe enough to enter.

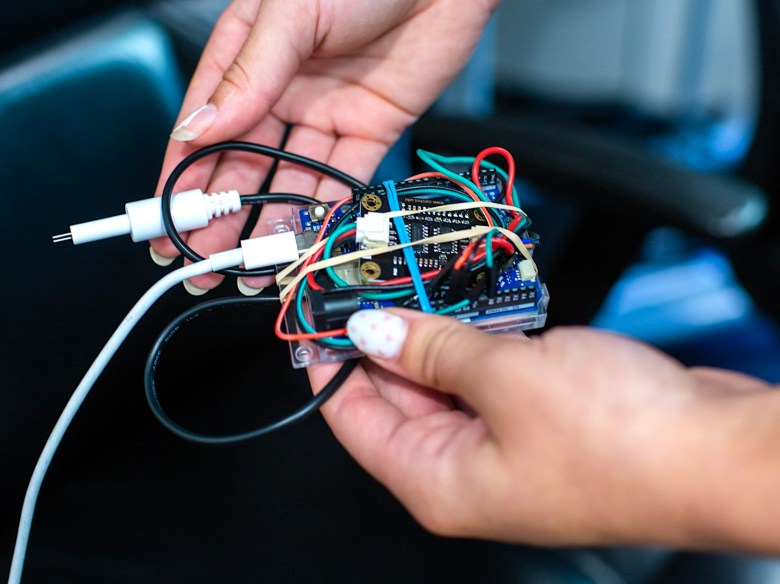

Piper Johnson made her sewage sensor from off-the-shelf parts. Coding the software was the hard part. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Piper Johnson made her sewage sensor from off-the-shelf parts. Coding the software was the hard part. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

SF’s current system isn’t fast enough. The Public Utilities Commission and Department of Public Health monitor bacteria levels, but samples are only taken weekly and often take a day to process. Johnson’s prototype works in seconds — at least in a lab.

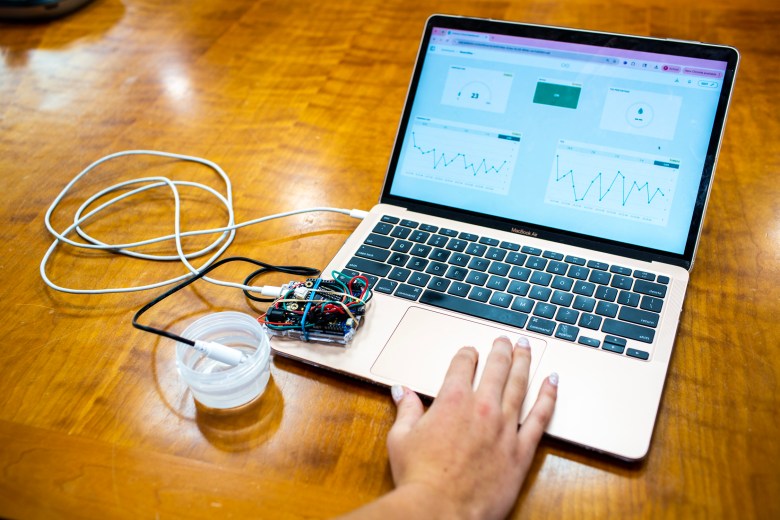

One recent morning on campus, she showed off the sensor, immersed in a cup of distilled water. Its reading (“total dissolved solids”) was displayed on a laptop connected via a cable you can buy for a few bucks at the nearby Daiso in Japantown. When she added salt to the cup, the numbers went up. Most of the sensor itself, based on a circuit board, is an off-the-shelf product. Coding is the hard part.

A data dashboard displays the changing levels of dissolved solids detected by Johnson’s sensor. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

A data dashboard displays the changing levels of dissolved solids detected by Johnson’s sensor. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Getting her prototype to show data from multiple sensors at the same time was extra tricky, Johnson said. One of her goals this year is to create an online dashboard for the public to read in real time.

Johnson thinks she’s found a workaround to the long wait for results that the city’s current testing requires. She’s not testing for bacteria. Instead, her sensor scans for dissolved solids and turbidity, or cloudiness.

Time spent at the beach with Teddy, as well as her love of marine animals, inspired Piper Johnson to take on water pollution. (Photo: Piper Johnson)

Time spent at the beach with Teddy, as well as her love of marine animals, inspired Piper Johnson to take on water pollution. (Photo: Piper Johnson)

These are only proxies for unhealthy levels of contamination. The amount of dissolved solids and haze in the water don’t necessarily indicate harmful bacteria (read: poop). But Johnson thinks that another layer of information — the historical data the city has collected over time — could combine with the sensor data and help surfers and swimmers assess water safety.

“There’s no way to definitely say what’s in the water without analyzing the water every second, which is impossible,” said Johnson. “But I think it can really give us a good estimate, especially comparing with the local weather.”

Johnson’s sensor is WiFi capable, and she hopes to use this to transmit data remotely when it’s deployed. She’ll use a 3D printer to create a waterproof buoy to make her prototype seaworthy. She’s also applying for grants to buy an ammonia sensor to add to the circuit board, offering another data point to evaluate water safety. Johnson plans to test it near the stormwater overflow site where Lincoln Way meets Ocean Beach.

Down the road, Johnson is considering going into veterinary medicine. That dream and her project are inspired by her love — and concern — for animals, especially marine wildlife. “They have to live in this every single day,” she said, “and they can’t just not go in the water.”

An early start

While Johnson won’t be displaying her project this weekend at the Bay Area Science Festival, other local kids will be, including a team from Presidio Middle School, according to the festival map.

To ask about festival participation, The Frisc reached out to several SF public school staff, including at Galileo, the district’s STEM high school. They either did not respond or referred The Frisc to district spokespeople.

Kids at a previous Bay Area Science Festival at a robotics exhibit. (Courtesy of the Bay Area Science Festival)

Kids at a previous Bay Area Science Festival at a robotics exhibit. (Courtesy of the Bay Area Science Festival)

“Students are connected to many science-related projects and opportunities and work with UCSF scientists,” district spokesperson Katrina Kincade said via email. (SFUSD students tested 10 percent higher than the state average for California science standards in 2024.)

Johnson, who attended public elementary school, said she was curious about the natural world around her at a young age. Heather Wygant, SF regional director for the California Association of Science Educators, said that kind of early interest is important, though most elementary schools often focus more on reading and math.

“In general, K-5 [students] spend the least time on science,” she said. “By middle school, science is taught regularly, but many come to middle school lacking the skills they should have developed in K-5th grades.”

SF Board of Education president Phil Kim noted that SFUSD has invested in a K-8 core science curriculum as a step toward that goal. “We are the STEM capital of the world here,” said Kim in an interview. “The more that we can introduce concepts as early and often as possible, the stronger it is for our students.”

Disclosure: The Frisc’s editor is the parent of a Sacred Heart Cathedral student.

More from The Frisc…