Some 500 Black families were displaced from West Oakland during the construction of the I-980 freeway during the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. Now, a major event in West Oakland this weekend will help residents understand a few possibilities for how to undo that racial injustice — through a program called Vision 980.

Hosted by Evoak!, the Oakland nonprofit dedicated to advancing equity and sustainability, the event will take place at Oakland’s Preservation Park this Saturday, Oct. 25, and will feature oral history circles to share stories of the displaced, film screenings, steamroller printmaking, Minecraft-style building games, and hands-on 3D modeling to help participants reimagine the landscape. The event will run from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Over the last decade, state officials have engaged in conversations with developers, planners, and residents about whether to remove or radically alter the freeway. The idea is that the large trench where the I-980 is situated, disrupting more than 10 city blocks, could be used for housing and public parks. Changes could more directly connect the people of West Oakland to services and shops downtown in safer ways than the current overpasses and dangerous intersections where people speed.

The title of the event, “From Freeway to Future: Honoring the Past, Designing the Future,” speaks to the project’s ambitious goals. On the event website, the hosts say the event, which they call a block party, “builds on West Oakland’s cultural legacy with a commitment to policy change around comprehensive creative community development.”

Vision 980, the program looking into the future of the corridor, is led by the state transportation department, Caltrans — and Randolph Belle was contracted to run the program’s community-building and outreach. Belle said the block party is not officially a Caltrans event, but his team and state officials will be on hand to talk to people. The hope, he said, is that it will affect how Caltrain’s engineers develop the design for the I-980 project.

“It’s going to take more than any of us at the table to get this done,” he said. Belle told us he’s excited about West Oaklanders engaging with Saturday’s program — even if it might rain.

“We’re just going to go for it, and we have some indoor spaces as a Plan B,” he said.

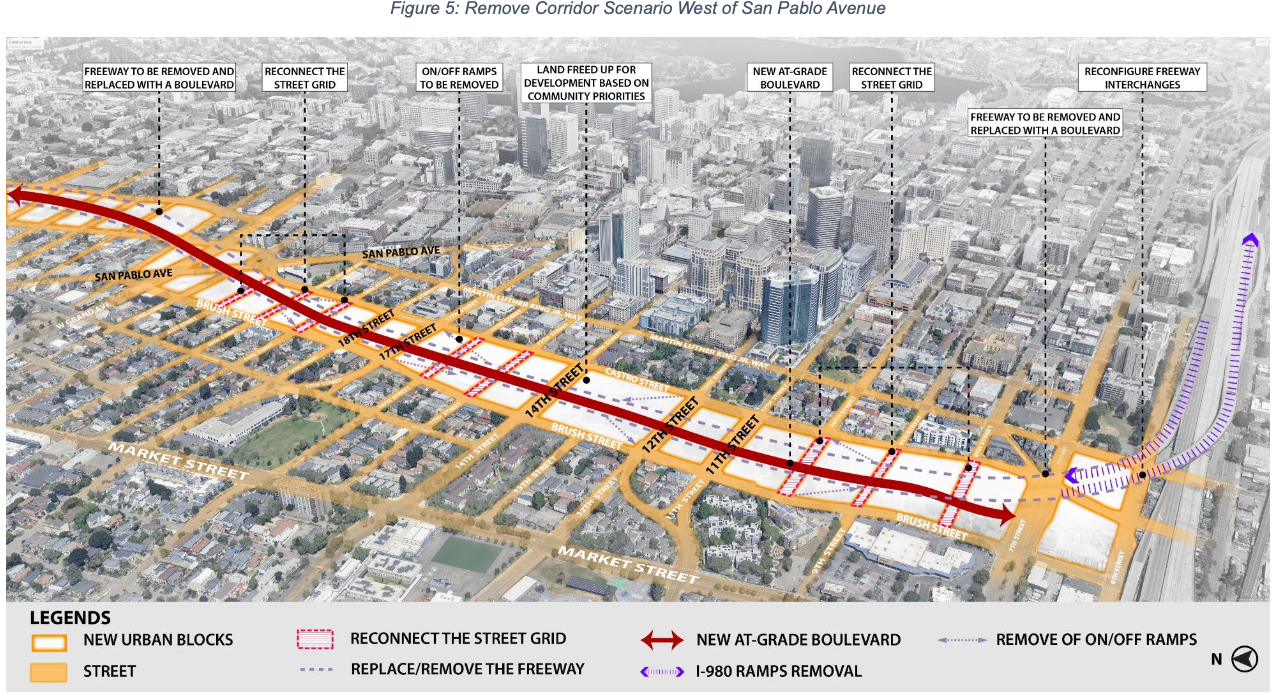

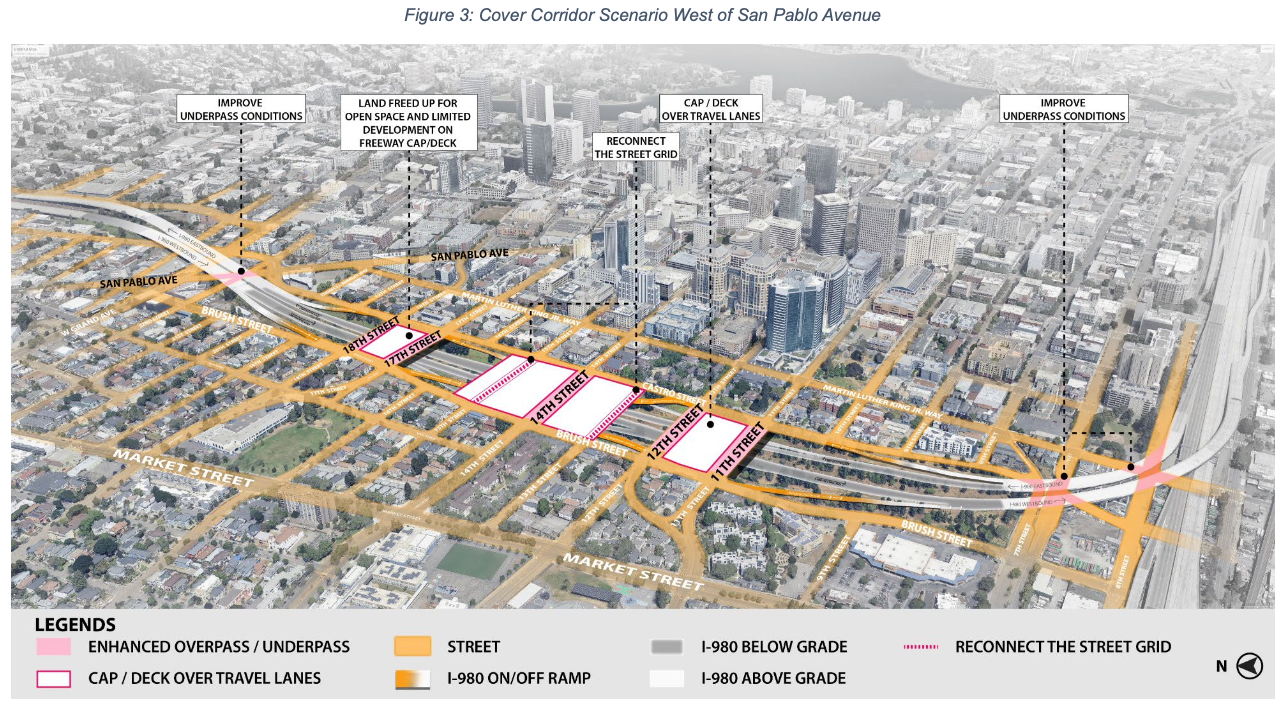

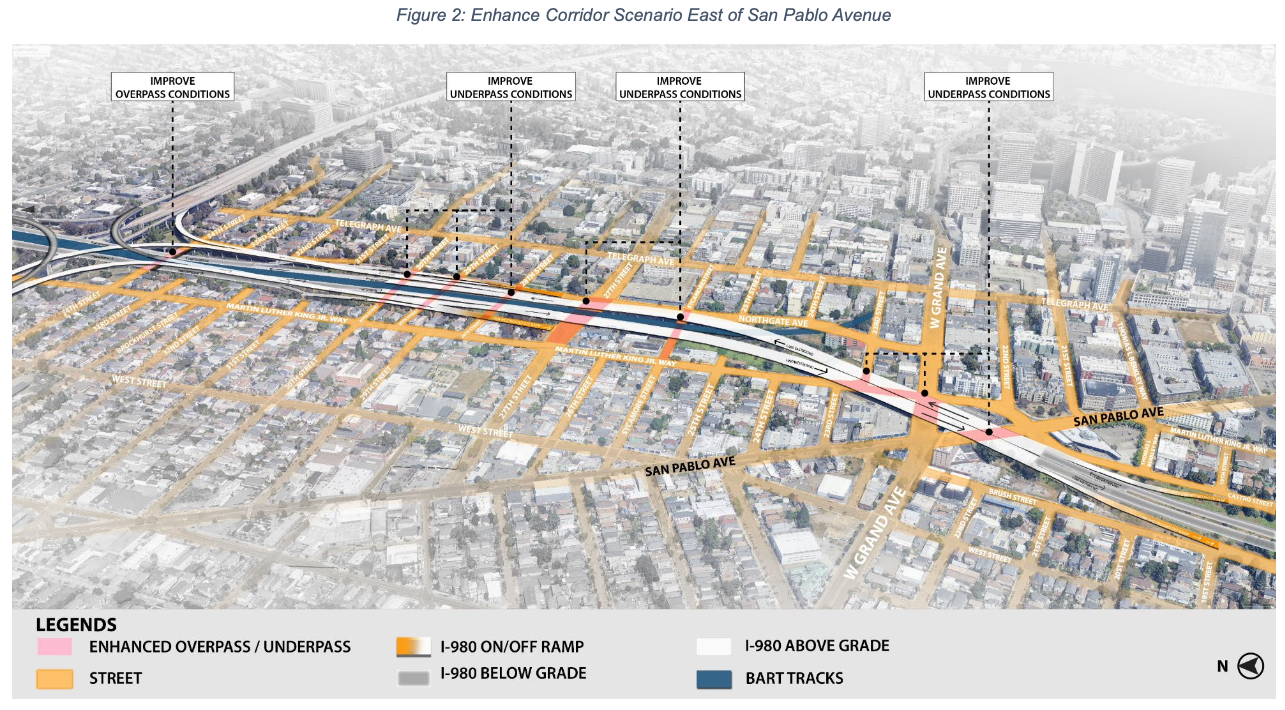

Caltrans has looked at three possible I-980 scenarios in preliminary surveys of Oakland residents, top to bottom: removing the freeway, capping it, or leaving it in place and enhancing the crossings. Credit: Caltrans and Vision 980

Caltrans has looked at three possible I-980 scenarios in preliminary surveys of Oakland residents, top to bottom: removing the freeway, capping it, or leaving it in place and enhancing the crossings. Credit: Caltrans and Vision 980

In a previous interview earlier in the Vision 980 process, Belle acknowledged that many in Oakland’s Black community were distrustful of past government plans and promises that negatively affected their families. That’s why, he said, one focus of his group’s Vision 980 work was to identify and quantify the lifetime costs of racism so West Oakland’s Black communities could be fairly compensated through viable housing and financing options.

In that vein, Belle said one of the most interesting parts of Saturday’s event will be a “data station” where people can learn about how the freeway construction, redlining, and bank disinvestment all worked together to squeeze West Oaklanders. Belle said local college students have been working on the data and presentation for a few months.

“By connecting numbers to real stories,” the event description says, “the station empowers participants to understand harm in measurable terms and to imagine how future investments could repair and restore value to the community.”

Latest Caltrans survey had only 7% Black respondents

As the event nears, Caltrans released the results of its latest outreach survey into potential changes to the corridor. Many of the 1,900 people surveyed last summer said they wanted to see anti-displacement guarantees and a commitment that any new housing be affordable.

The survey, run by Caltrans and separate from Belle’s community outreach, asked people their thoughts about three potential futures for the I-980: to improve it through enhancements, to cover it, or to remove it.

The study found that removal of the highway and replacing it with a boulevard had the highest potential for advancing equity, with Caltrans’ scoring method finding it would lead to the most road safety and would create up to 90 acres for potential housing development. But many people surveyed were wary about adding a lot of new housing that could lead to the exact thing that happened 40 years ago — displacement.

The second option, to cap the freeway, would create up to 25 new acres of land, which could be developed into housing or parks and could also involve roadway improvements. Those surveyed liked this option the least because they thought it would lead to continued air pollution, which people would be exposed to in any newly created parks.

The third option, enhancing the current corridors with improved crossings over the freeway, would cost the least and be the easiest to implement. Caltrans said this scenario did “not meet the goals of the study” because it would not “invest in the transformational changes needed to reconnect West Oakland to downtown, nor does it create any new land for development based on community priority.” Yet it was the respondents’ second-ranked scenario.

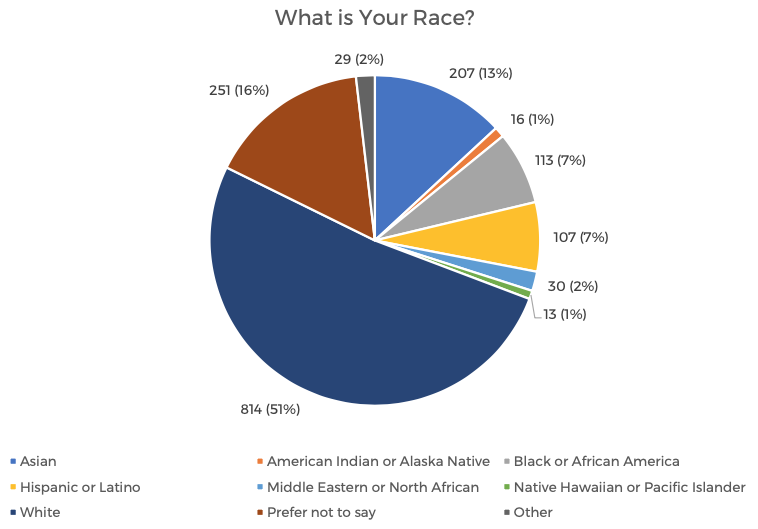

The survey respondents from this summer were overwhelmingly white, according to a Vision 980 chart. Credit: Caltrans and Vision 980

The survey respondents from this summer were overwhelmingly white, according to a Vision 980 chart. Credit: Caltrans and Vision 980

Among the 1,580 people who provided their race, only 7% (113) identified as Black. Given that the whole project is built upon the idea that the I-980 most wronged Black West Oakland communities, that response number is troubling.

Elizabeth Deakin, professor emerita of planning and urban design at UC Berkeley, told us that the survey didn’t get a population-representative response but that, unfortunately, “is a common result.”

“Engaging the community in an early, relatively abstract stage of planning is always a challenge,” Deakin said. She said it may be possible to get more engagement later on when preliminary answers are in place about surface street design, traffic impacts, costs, and where the money would come from.

Deakin said the steps the outreach team had taken — leaflets, surveys, meeting with key groups — were “pretty standard,” but involving health clinics and churches could help to get the word out more. Overall, she said, the concerns raised by the survey respondents were necessary and valuable, including what “land development options might accrue and for whom.”

She also noted that the team could include a fourth possible option for the freeway’s future: removing it and not building a boulevard, an idea suggested by some survey participants.

Randoph Charles Belle has been working “nonstop” to put on the block party event this Saturday at Preservation Park. Credit: Florence Middleton for The Oaklandside

Randoph Charles Belle has been working “nonstop” to put on the block party event this Saturday at Preservation Park. Credit: Florence Middleton for The Oaklandside

Belle said that his outreach efforts so far, which were separate from the summer Caltrans survey, “were more squarely focused on legacy residents.” Belle said he’s also sent out 5,500 postcards to West Oakland residents to get them to engage.

This Vision 980 study was the second round of Caltrans’ public engagement surveys, all part of Phase 1 of the Vision 980 project. Phase 2 will include technical feasibility studies that will begin in 2026 and end in late 2027, according to Caltrans.

Belle, who is a Black Oakland resident of more than 30 years, told us that he has noticed some trends in how Black old-timers are discussing the future of the I-980.

“‘We just don’t want to get fucked again,’” is what he’s heard. “‘We don’t want any redevelopment to be exacerbated.’ ‘Fuck that — you took all these businesses and you’re going to give us back a park?’ Anything that gets built will have a percentage of open space anyway. We are going to prioritize harm repair. Housing, economic development, health, cultural preservation — that’s our four pillars.”

“*” indicates required fields