His father, Renee Yañez, cofounder of San Francisco’s Galería de la Raza, brought the first Día de Los Muertos public art exhibition to the city in 1972. Along with his colleague, the late artist and curator Ralph Maradiaga, he created an annual event for people to collectively mourn, celebrate and honor those who’ve passed on.

Over the years the exhibition has been shown at Galería de la Raza and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, before finding its current home at SOMArts 25 years ago. Yañez worked on this show with his father every year from 2005 up until the elder passed in 2018.

Now through the exhibition’s closing reception, SOMArts’ gallery will be occupied with this year’s collection of altars — pieces that artists have dedicated “to parts of themselves,” says Yañez, “or their relationships to others that they are mourning.”

Monique D. López’s ‘Amor Eterno’ 2025 at SOMArts. (Claire S Burke)

Monique D. López’s ‘Amor Eterno’ 2025 at SOMArts. (Claire S Burke)

The artworks are bright, fluorescent even. There are large painted sculptures, and a small dome you can enter and read written messages of all sorts. Some are more subtle and intimate, while others oppose oppressive forces or touch on current events.

Many of the pieces in the exhibition are both personal and topical, like work that champions trans rights. This show, says Yañez, has always been about highlighting issues of our time.

Yañez recalls being a kid and seeing his father curate shows as a response to the first wave of the AIDS crisis and Operation Desert Storm. Later, the shows shed light on lives lost in Hurricane Katrina and the Pulse nightclub shooting.

“There’s always been a sense of urgency in how the show responds to what’s going on in the world,” says Yañez. “That is [my father’s] legacy in the show. As his son, that’s something I strive to continue.”

The biggest issue reflected in this year’s show, according to Yañez, is President Trump’s policies — specifically in regards to immigration, as well as anti-trans legislation. “I wish I didn’t have to say that,” Yañez says. “But that’s the reality that we’re living in.”

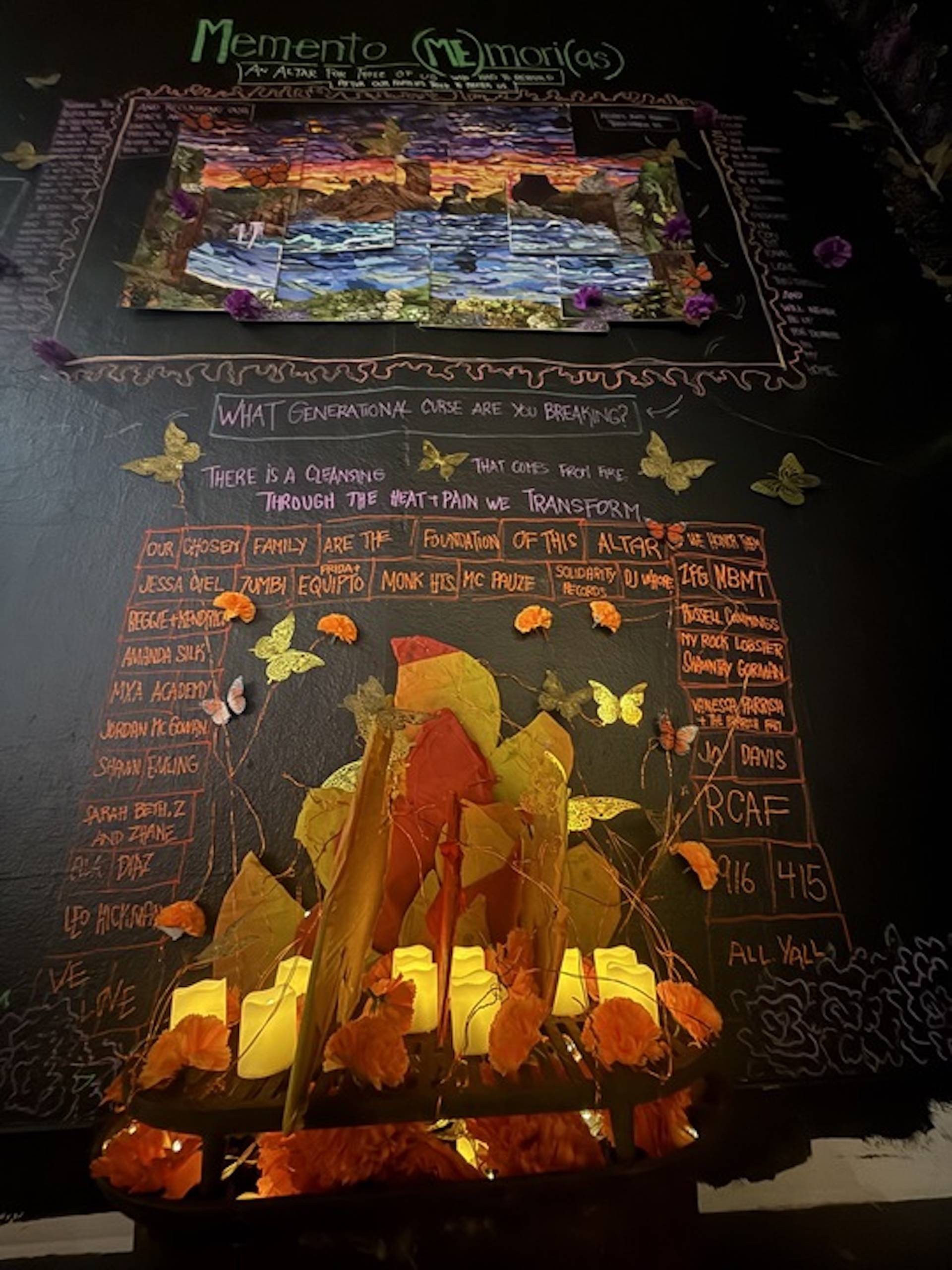

Liv Styler, ‘Memento (Me)mori(as),’ shown at SOMArts’ Día de Los Muertos exhibition. (Claire S Burke)

Liv Styler, ‘Memento (Me)mori(as),’ shown at SOMArts’ Día de Los Muertos exhibition. (Claire S Burke)

Alongside colorful displays of love for people who’ve passed, artists have also created memorials to ideas that have withered, or small shrines to their future selves.

Just inside of the gallery stands Liv Styler‘s “Memento (Me)mori(as),” a work of art that encompasses two large walls, and asks audiences to redefine their idea of familial connections. One wall shows portraits of Styler and her children, while the other wall is decorated with Monarch butterflies emerging from what she calls “a painful transition” in a fireplace and ascending skyward toward a still-life painting, then beyond.

The butterflies are courtesy of her Mexican heritage. Both the painting and the fireplace, centerpieces in the artwork, are creative remixes of Styler’s childhood home.

“We had no art,” says Styler. “We had nothing in our home. It was a very colorless, lifeless, joyless space. But there was this one ugly-ass landscape.”

Liv Styler’s ‘Memento (Me)mori(as).’ (Pendarvis Harshaw)

Liv Styler’s ‘Memento (Me)mori(as).’ (Pendarvis Harshaw)

Styler chose to recreate the landscape in her own way, reflecting how she learned to create an “internal world” that was full of the color she wasn’t feeling at home.

“Instead of doing the horrifically boring greens and browns,” she says of the original piece, “I recreated it in the way that I wanted to see it — which looked like Lisa Frank kinda exploded all over it.”

Below the landscape, the fireplace in Styler’s work is lined with bricks that bear the names of some of her closest friends — artists and activists, some still living and some who have passed on, all of them chosen family.

“The bricks were one of the last things I did,” says Styler, charting the steps of her creative process. “It really forced me to reflect on [the chosen family] concept the whole time. Those are the people that transformed me.”

Styler says her work confronts the idea of blindly honoring blood-related ancestors — specifically those who might not have accepted different gender identities. She turns that on the audience as well, with the words “what generational curse are you breaking?” written as a prompt. Sticky notes and pens are available for visitors to write messages reflecting on how they’ve honored themselves, made a brave choice or broken a family curse.

“I really hope there’s some folks out there who walk through it and have had a similar familial experience, where they just aren’t really sure about their ancestors,” she says. For those who feel like she does, Styler says, “There’s always family out there for you. There’s always people out there who are gonna love you, and you just have to go and find them.”

Sometimes, she says, in order to find that chosen family, you have to go through trials and tribulations, and make changes like the butterflies in her work.

“And then,” she says, “as you heal and you become that new version of yourself, and that ancestor infuses into you, you find that chosen family a lot easier.”