On the Shelf

The Last Kings of Hollywood: Coppola, Lucas, Spielberg—and the Battle for the Soul of American Cinema

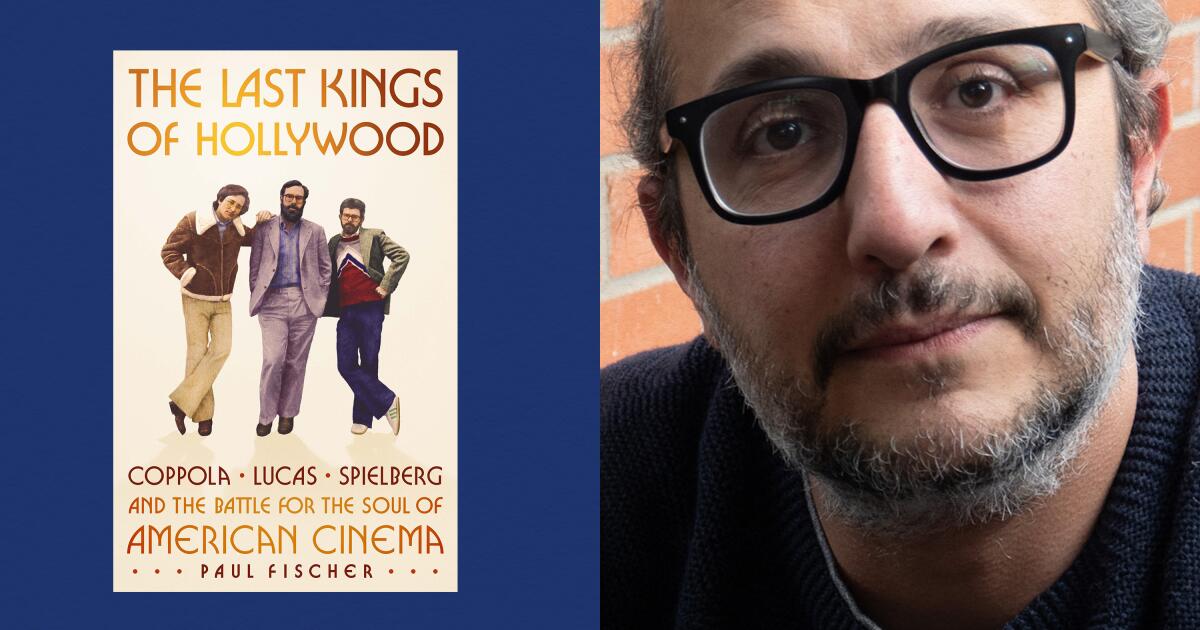

By Paul Fischer

Celadon Books: 480 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Paul Fischer showed “Jaws” to his daughter when she was 10. She wasn’t scared. In fact, she loved it so much that she dressed as Richard Dreyfuss’ Hooper for Halloween. To Fischer, who watched “Raiders of the Lost Ark” at age 4 (“I remember the melting heads but I don’t think I was traumatized”), it shows the staying power of some of the ’70s blockbusters.

“It’s the flip side of how these franchises became so massive and had such a long tail,” he said in a recent video call with The Times, discussing how each generation still finds “Star Wars,” “Raiders,” “E.T.,” “Jaws” and “The Godfather.” “They’ve created films that endured and that overshadow others.”

That is part of the impetus behind his new book, “The Last Kings of Hollywood: Coppola, Lucas, Spielberg—and the Battle for the Soul of American Cinema.” The book, Fischer’s third about film history, starts before the trio were “big mythical names” and instead were just a bunch of guys setting out to fulfill their dreams.

The narrative then follows their journeys from the late ’60s through the early ’80s, filling in the “ecosystem” the trio came up in and how they wanted to change the system to gain creative autonomy. Spielberg worked within the system, Coppola spent lavishly and even ostentatiously to build his own studio and Lucas found his independence through a quieter, more conservative and technology-driven route.

(Martin Scorsese, who was friends with the three and “the most interesting human being of that generation of filmmakers,” gets plenty of ink but was not a titular character, Fischer said, because he remained an outsider who just wanted to make movies, not change the system.)

“I’m not going to pretend I can tell you what was going on in their heads but I tried to make people feel like they were there when it happened,” Fischer said.

While none of the three men would be interviewed, Fischer had decades of quotes and conducted his own interviews with hundreds of people in the filmmakers’ orbits to get a fuller and more honest story. (He added that their representatives were uniformly helpful with fact-checking and providing photos. “There was never a door closed on me,” he said in an accidental reference to the final scene of “The Godfather.”)

Coppola, “who changed quite a bit, was the hardest one for me to pin down,” Fischer said. “There are layers of complexity to him and his willingness to treat the creative life as if it’s an experiment.” Blending that with his self-indulgent philandering and spending of money, he added, “you can change your mind about that guy every five minutes.”

During that era at least, Fischer said Lucas and Coppola seemed ”completely devoid of any self-awareness.” He chronicles how Coppola pressured Lucas to accept changes to his first feature, “THX 1138,” so the studio would release it while Lucas viewed that as Coppola pushing him to sell out. Meanwhile, Lucas was pushing Coppola to do a studio film for hire to keep his fledgling Zoetrope Studio afloat, making Coppola feel pressured to sell out. (That movie was “The Godfather,” so it worked out OK for Coppola.)

“They keep giving each other advice about how to do things and then betray that same advice when it applies themselves,” he said, although he added that he doesn’t “whip them for 300 pages for having giant egos,” and said it’s part of the recipe to be a visionary filmmaker, especially in the Hollywood studio system.

Ultimately, the book depicts Lucas as more of a sellout, acting like the studio suits he once detested as he pressures “The Empire Strikes Back” director Irvin Kershner to make changes, often based on budget and then focusing more on profitability as he conjured up characters like the Ewoks for “Return of the Jedi.” Fischer doesn’t believe Lucas would recognize that version of himself in the book. “He’s someone who lost his BS detector and has drunk his own Kool-Aid.”

In Fischer’s telling, the creative and business sides are interwoven and inseparable from each other and from the personal relationships — their friendships and rivalries with each other but also their relationships with those who worked for them or loved them.

“They were all able to do what they did because of wives or partners or friends or college classmates, who did a lot of the work without being household names,” he said. To fully tell the story, he devotes plenty of narrative space to Coppola’s wife Eleanor, and his most prominent mistress, Melissa Mathison, who later wrote “E.T.,” producer Kathleen Kennedy, who co-founded Amblin Entertainment with Spielberg, and Lucas’ wife, Marcia, who edited the first “Star Wars” trilogy (and Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver”).

“How did these guys break through? Well, they were middle-class white dudes and these women looked after some of this stuff they couldn’t,” Fischer said. “Those aren’t the only reasons these guys became who they did but without that, they probably [wouldn’t have].”

Fischer celebrates the three men’s vision and talents — he calls “The Godfather” “a perfect film” and says Spielberg “speaks the language of a camera better than anybody else”— but the book makes clear how often they got lucky or were saved from themselves.

If Coppola had spent his money more judiciously, he might not have done “The Godfather;” Lucas resisted hiring Harrison Ford to play Han Solo as well as Ford’s creative contributions; and if someone had bankrolled the first feature film Spielberg pitched before latching onto “Jaws” — “a sex comedy San Francisco Chinese laundry riff on Snow White” — it could have sunk his career.

Additionally, Lucas and Coppola’s friendship frayed when the latter snatched back the directing gig for a film he had long ago promised to his buddy. “But imagine George Lucas making some weird low-budget, ‘Battle of Algiers’ version of ‘Apocalypse Now’ in the back streets of Sacramento,” Fischer said. “That sounds pretty crappy. And we would have lost one of the great, novelistic experiential movies that we have.”

Lucas, meanwhile, dangled his idea for “Raiders of the Lost Ark” before Spielberg’s eyes, then told him that Philip Kaufman had dibs. “He’s a fine director but we would have lost something there too,” Fischer said. “There are these crossroads there but still there has got to be something special about these three or they couldn’t have had repeated successes like they did.”

Writing about their failures, foibles and frustrations did not lessen the hold that these three men and their movie magic have on Fischer. He recounts a story of his own connection to one film with undisguised delight and enthusiasm. After graduating film school at USC, he was producing a documentary (“Radioman”) in New York when he learned that “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” was doing some filming in Connecticut. “Obsessed,” he finagled his way onto the set and into a job. “All I did was turn off the air conditioning,” he said. “‘Roll camera,’ I flip it off. ‘Cut,’ I turn it on. I did that for four days. But when Harrison Ford walked by wearing that jacket, I was 5-years-old again. That was cool.”

Miller is a freelance writer in Brooklyn who frequently writes about movies.