Why this matters

Housing advocates praise the law as transformative. North County officials worry about losing local control.

GT Wharton is tired of seeing the Oceanside Transit Center have little besides a parking lot. As co-founder of Strong Towns Oceanside, a nonprofit dedicated to safe, walkable communities, he’s been part of the effort to push the city to approve a project that would add hundreds of housing units and shops to the transit center.

GT Wharton is the co-founder of Strong Towns Oceanside, a nonprofit dedicated to safe, walkable communities. (Courtesy of GT Wharton).

GT Wharton is the co-founder of Strong Towns Oceanside, a nonprofit dedicated to safe, walkable communities. (Courtesy of GT Wharton).

“We would love to see more housing, especially any type of housing that isn’t single-family detached housing, especially those that are built out in the periphery of our cities,” Wharton told inewsource. “We’d like to see more housing downtown and especially in transit so that people can go car free or car light.”

The Oceanside Transit Center redevelopment plan is one of 11 “transit oriented development” projects that the North County Transit District has embarked on to revitalize its stops, something it hopes will help increase cities with housing crises and increase ridership.

It is those same motivations that led to a law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last week. Senate Bill 79 allows for more housing development near major public transportation stops.

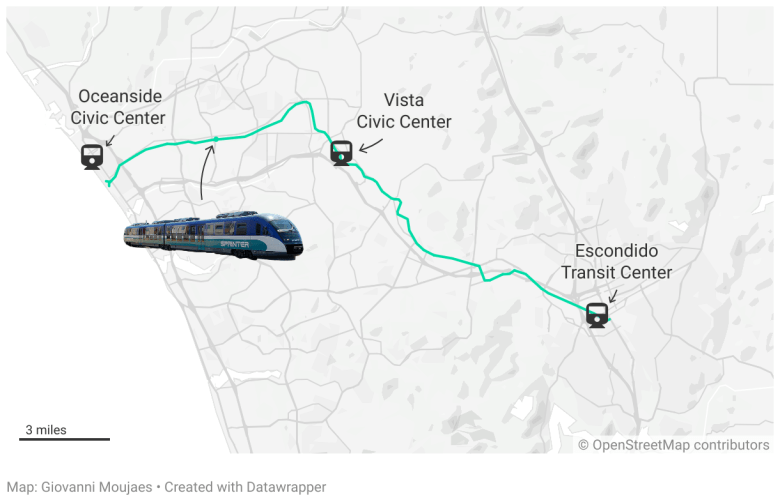

An amendment to the law removed stops along rail lines with fewer than 48 trips per day, which exempted North County’s 30-trip per day Coaster line. SB 79 will apply to the Sprinter line, which connects Oceanside, Vista, San Marcos and Escondido, with 15 stations along the way. A total of 455 Sprinter trains run every week.

The law has been praised by housing advocates but opposed by North County cities and its transit district. Housing groups say adding housing argue that despite these benefits, a statewide law impedes local control over city planning.

North County Transit District CEO Shawn Donaghy told inewsource that the law may be right for the Bay Area – but not for North County projects.

“I think we have really good partnerships with our communities, and that’s really what drives big projects, for me, is the buy-in from the city,” Donaghy said. “I think this bill has the potential to maybe change those relationships a little bit if they think that we have authority over things that historically we would have worked on together.”

Housing, environmental benefits

Advocates for SB 79 say the demand for local control is a leading contributor to the housing crisis around the state.

“Ultimately, we’re in our housing shortage because of local control,” said Saad Asad, a communications manager for California YIMBY, a pro-housing group that advocated for the bill. “Every city thinks it’s like a snowflake that is super special, and it says that this is our character, this is how this should be, go build somewhere else. And then if you have all 18 jurisdictions in San Diego County saying that, then there really isn’t any place to build.”

Asad added that the law still leaves room for local control. Cities are still able to have the final say on the design of the project and affordability designations.

For Nicole Capretz, CEO of Climate Action Campaign, building housing next to public transportation is also a critical climate solution.

“This is not only a key climate solution, it’s a key public health and opportunity,” she said. “It’s the best location for housing.”

Sprinter line project plans — and what local leaders have to say about them

Some North County cities have a history of fighting the state on housing policy, and SB 79 was no exception: Encinitas, Oceanside, Vista, Carlsbad, Del Mar and Solana Beach all opposed it.

Many leaders said they agreed with the benefits of putting housing near transit, but did not want mandates coming from the state.

State Sen. Catherine Blakespear, who has historically advocated for more housing dating back to when she was Encinitas mayor, voted against SB 79. She said that mayors and council members in her district were “vehemently opposed,” as were the 618 residents who contacted her office.

“Although I am a strong proponent of creating more affordable housing‚ I voted against this legislation. That’s because SB 79 would allow transit agencies to go around local governments’ decision-making processes in determining where to put denser housing,” she wrote in a recent newsletter.

The law’s author, Sen. Scott Wiener of San Francisco, amended it in the final stages. Transit centers that only serve the Amtrak or Coaster, which runs along North County’s coast, were excluded, leaving most of coastal North County out of the effects of the legislation.

Aside from the law, the North County Transit District is committed to building more housing near its transit stops. The districts’ 11 projects are in varying stages. Even after it partners with developers, getting approved by the City Council can be a large hurdle.

A few mayors of cities with projects along – and near – the Sprinter line shared their trepidations about the law:

They include the city of Oceanside, which is in the midst of debates over its transit center.

“Oceanside is a strong supporter of sustainable mobility and transit-oriented development,” Oceanside Mayor Esther Sanchez wrote in a letter to the Legislature opposing the law. “However, SB 79’s rigid, one-size-fits-all land use mandates remove local discretion and risk undermining thoughtful planning that takes into account both state priorities and community needs.”

At an October City Council meeting, Sanchez expressed support for plans to build more than 700 units, a hotel and commercial space at the Oceanside Transit Center. But she said she was wary of specific components like the congestion from the bus route in the area.

The project has been delayed over the years, including earlier this month, when Oceanside voted to push the conversation again to its Nov. 19 session.

Dozens of speakers expressed support for the project, though many also were concerned about environmental effects and congestion. The developer and the transit district’s CEO said they were frustrated at the council’s delay.

“We’ve been waiting since 2008 to develop this land,” Donaghy said. “We’re on extension number seven.”

A week after that meeting, Donaghy told inewsource that he understands why the City Council asks the questions they ask, and he appreciates the relationships with the city. He said he worried the law would give the transit district authority over what has historically been a collaborative process.

Vista Mayor John Franklin said he was not sure how SB 79 would affect the city yet, but he disliked it at face value due to the removal of local control. Residents have the ability to bring concerns about projects to City Council who will listen to them, Franklin said. That’s not something that is possible at the legislative level.

“We live in a suburban and semi-rural community, and those of us who chose Vista as our home, chose it for that density,” Franklin told inewsource. “We need to build enough homes for our children without becoming Los Angeles.”

The transit district entered an agreement to redevelop the Vista Civic Center Station.

The developer plans to build 131 apartments and 2,000 square feet of retail space.

The transit district has yet to submit plans or timelines to the City of Vista, according to Fred Tracy, communications officer for the city.

The Escondido Transit Center is one of the largest transit redevelopment sites in the region, according to Donaghy. He said it is slated to be one of the next projects and will have housing units.

Carlsbad

Carlsbad’s Coaster station does not appear to meet the requirements in SB 79. In an October planning commission meeting, officials said they still were not certain and were awaiting guidance from the state.

The North County Transit District is also in the early stages of a development project at the Carlsbad Village Station.

“The transportation and utilities infrastructure in Carlsbad is not suitable for the level of density SB 79 would impose,” Carlsbad Mayor Keith Blackburn wrote in a September letter. “Our transit options — primarily the North County Transit District’s Coaster commuter rail and a limited bus network — do not provide the frequency or accessibility of service found in major metropolitan centers. While our Coaster station may technically qualify as a TOD stop, the surrounding area lacks the infrastructure and amenities necessary to support such high-density development.”

Type of Content

News: Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.