“The average squatter,” says James Jacobs, “has no melee experience.”

No familiarity with katana swords or other bladed weaponry. No training in kendo, iaido, or other martial arts.

If anyone knows the typical combat background of a squatter, a person living in a home illegally, it’s Jacobs. He runs a company called ASAP Squatter Removal, offering do-it-himself eviction services to property owners throughout the Bay Area.

Say a homeowner or bank or landlord discovers somebody occupying their property without authorization. They could call the police, though officers might not come. Police tend to shy away from tenancy disputes, leaving them to the civil courts. The property owner could go ahead and file an eviction lawsuit, but that can drag on for months.

Or they can call Jacobs.

For a fee, Jacobs will surveil the place and force out the people inside of it using a complex concoction of homespun arms and militarized tactics.

Jacobs’ team will often complete a job in a matter of days by boarding up the joint and moving in temporarily themselves, to make sure the squatters don’t return. But if they do, Jacobs is prepared for battle.

ASAP Squatter Removal is not alone. There’s a cottage industry in California that helps property owners force out squatters. There’s Squatter Squad, based in Southern California, and a handful of other companies, most established over the past couple of years.

But ASAP’s materials might be the most eye-catching — photographs peppering its website depict what the company describes as “dangerous squatters” holding shotguns and rifles, including a boy who looks to be about 5 years old. These images appear to be variously sourced from a gun rights documentary, stock image websites, and articles about encampment residents in Los Angeles and the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico. Jacobs markets his company as the only squatter removal business with a Yelp account.

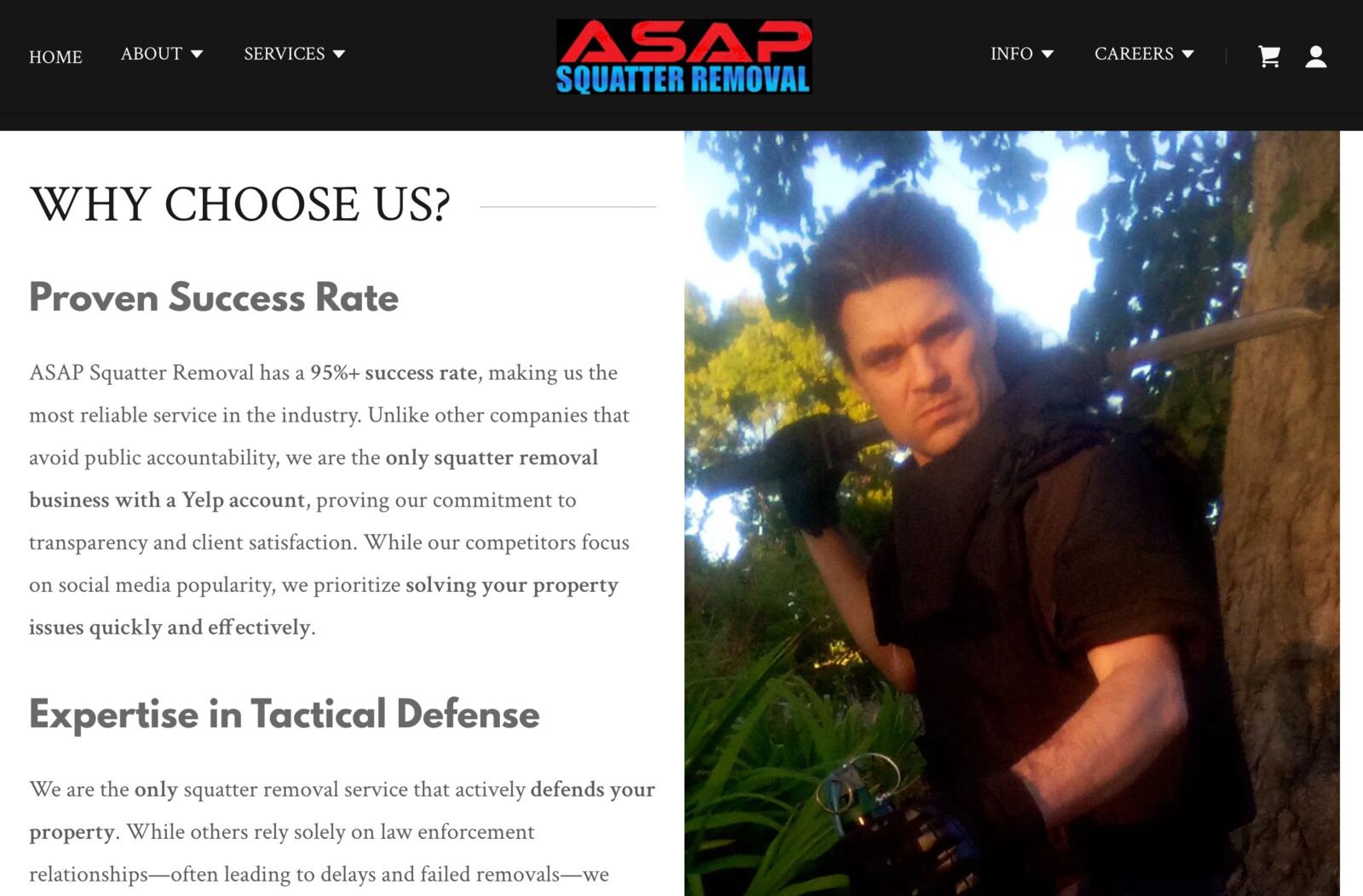

James Jacobs, armed with a sword and a grenade, on the ASAP Squatter Removal website. Credit: Screenshot of asapsquatter.com.

James Jacobs, armed with a sword and a grenade, on the ASAP Squatter Removal website. Credit: Screenshot of asapsquatter.com.

Jacobs reached out to The Oaklandside several months ago to publicize his business. We spoke with him in depth over multiple interviews, talked to one of his contractors, and spoke with a client who hired ASAP Squatter Removal to kick out uninvited residents in West Oakland.

We were able to confirm a recent job Jacobs took in Oakland, and videos he posts show him and some of his contractors working at other properties. However, he declined to share proof of some of the squatter removals he’s been responsible for and other statements, saying he signs non-disclosure agreements with clients and that his lawyer advised against sharing anything about legal proceedings. And few public records about his company exist; ASAP Squatter Removal isn’t registered with the California Secretary of State, though Jacobs says this is in the works.

While we have ongoing questions about some details of Jacobs’ business, the mere existence of ASAP Squatter Removal demonstrates the intense pressures in the East Bay’s housing landscape — and points to an industry that’s quietly growing in response.

The East Bay’s housing crunch is a breeding ground for tension

In the wake of the pandemic and eviction moratorium, landlords are feeling resentful and tenants are feeling squeezed. Credit: Florence Middleton for The Oaklandside

In the wake of the pandemic and eviction moratorium, landlords are feeling resentful and tenants are feeling squeezed. Credit: Florence Middleton for The Oaklandside

The Bay Area has been buckling under an affordability crisis and housing shortage for over a decade. Oakland’s homelessness numbers are at record levels, with an estimated 5,500 people lacking housing in the city. The growth in the unhoused population follows generations of underbuilding and discriminatory housing policies in the region, as well as the rising use of highly addictive drugs and a broken mental healthcare system.

Yet, in spite of all the people in need of housing, thousands of units sit vacant in the city, sometimes for years or longer, due to abandonment, family disputes, or speculation.

It’s impossible to know how many people are living without permission in these properties. But it’s not unreasonable to assume that the long tradition of squatting in Oakland — see: punk houses — has expanded as homes have become more unaffordable and other pressures have worsened.

To Jacobs, his work is righteous. He views squatting as theft, and his job as returning property to its rightful owner.

“I’d much rather make a squatter homeless than have a landlord lose property,” he said in an interview.

In California, squatters can pursue ownership of a building after five years, far more quickly than in most other states, and the formal eviction process can be expensive and lengthy. Oakland’s understaffed police department is often slow to respond or doesn’t at all, in Jacobs’ experience.

We asked the Oakland Police Department how they handle calls about squatters.

“Our officers will respond to investigate the nature of the call,” OPD said in a statement. “If our officers determine this is a landlord-tenant issue, the case will be referred to the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office for further investigation.”

The sheriff’s office gets involved once an eviction case has moved through court and resulted in a ruling supporting the landlord. Then, the sheriff will issue the tenant a notice, giving them at least five days to leave or obtain more time from a judge.

“We are bound to follow California law and cannot intervene unless directed by a valid court order,” sheriff spokesperson Sgt. Roberto Morales told us. “We urge property owners to rely on legal processes to avoid unintended consequences and ensure fairness for everyone involved.”

Daniel Yukelson, executive director of the Apartment Association of Los Angeles, has blogged about the increasing use of “vigilante squatter removers” among landlords, writing that the phenomenon is a reaction to law enforcement’s reluctance.

This approach is “far less costly and much faster than the court system,” he wrote, but noted that squatter removal is dangerous for both the squatters and the removers.

In a series of text messages, Jacobs wrote that the poor treatment of property owners whose buildings have been occupied is a real estate injustice scandal akin to: “Black codes, Jim Crow Segregation, deed restrictions, HOLC residential security maps, the California Alien Land Laws, Dawes Act, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and many more!”

He continued, “Every one of these laws I just mentioned were in effect less than 100 years ago and they all make me sick to my stomach. Real estate laws in the US have a deep history of injustice.”

Insisting he uses only legal tactics in his squatter-ousting endeavors, Jacobs can rattle off a number of criminal and property laws he employs to his advantage, and others that burden property owners. He claims the targets of his operations are increasingly sophisticated criminals who may not even sleep at a given property but instead use it for illicit activity like drug dealing.

I’d much rather make a squatter homeless than have a landlord lose property.

-James Jacobs

“The work we do is constantly changing,” Jacobs said. “It used to be that squatting was more of a homeless activity. Then it became more like organized crime. I’m kicking out a whole lot of gangs.” Oakland is the center of the “epidemic,” he said. OPD did not respond to questions about the extent of squatting in the city.

The Oaklandside has reported on cases where people occupying a building without permission have caused extensive property damage, like squatters who tagged, started a fire at, and flooded a new condo building almost ready to open in Adam’s Point. But many people working in the housing field and living in precarious circumstances say assertions like Jacobs’ dramatically mischaracterize most people who squat and misrepresent their motives.

For housing attorneys and a former squatter we spoke with, companies like Jacobs’ are symptoms of a dysfunctional system where property is treated as a profit-producing commodity instead of a shelter a person is entitled to.

“The only reason why businesses like this could exist,” said Tobias Damm-Luhr, staff attorney at the Sustainable Economies Law Center, is because “people hoard land and housing. They create these artificial scarcities such that people who don’t have a home or any other option are forced to try to live in places where they have no legal right to live.”

Surveillance and a quick removal on Adeline Street

A property owner hired Jacobs’ team after a person broke into a house on Adeline Street that was ready to go on the market. Credit: Natalie Orenstein/The Oaklandside

A property owner hired Jacobs’ team after a person broke into a house on Adeline Street that was ready to go on the market. Credit: Natalie Orenstein/The Oaklandside

About $250,000 in, Todd Pigott had completed the rehab of a duplex in West Oakland last year.

The project was one of hundreds of “fix and flips” his company has reported completing across the country. The place looked great, and Pigott was ready to list it.

Then, a person and three dogs moved into the bottom unit.

Pigott is used to occasional squatters. His company, ZINC Financial, is a private lender focused on distressed real estate. For years, California’s law worked fine for him, he said. If there were people living in a house he was renovating, he’d file an unlawful detainer — an eviction lawsuit — win the case, have the sheriffs come remove the occupants, and move on. It could cost about $1,000, but that was a relatively small business expense.

The COVID eviction ban, which lasted from 2020 to 2023 in Oakland, made the vast majority of evictions illegal. Landlords typically couldn’t issue eviction notices or get court orders to kick people out. However, evictions of squatters — called forcible detainers, not unlawful detainers — were still permitted, tenant and municipal attorneys told us.

When he noticed someone living at the Adeline Street property, Pigott called the police — 11 times, according to him. “Nobody responded,” he said. “Again and again.”

That’s when he turned to the internet and found ASAP Squatter Removal. He said he was “extremely skeptical,” but took a chance and reached out to Jacobs.

“I’m outside of my element,” Pigott said, recalling their first conversation. “I’m a father and a president of a finance company, and here I am with someone who’s talking about Tier 3 body armor and close-quarters combat training. I don’t really play in this arena. I walk my dog, ride my bike, go home, and hug my wife. But I’m desperate.”

He entered into a five-day agreement for surveillance and “sentry services” for $12,500, according to a contract and invoice we reviewed.

“Am I ever going to see this again?” Pigott remembers thinking about the large chunk of change. (In other places, Jacobs lists smaller fees for some of his services, like $700 for four days of surveillance, and referenced a much larger “$120,000 contract” with 24 crew members in an interview.)

Jacobs and his crew, Pigott said, surveilled the property as planned, eventually entering it. They “got the people out,” put their belongings outside, boarded up the building, and kept watch for a few more days to make sure nobody re-entered, according to the owner.

Jacobs’ approach, he raved, was “very professional and very methodical.”

A contractor who worked for Jacobs on this and reportedly about 20 other projects, an Iraq War veteran named Arthur Gutierrez, said the woman in the building moved out as soon as they told her to. But once someone else reportedly tried to break in, Jacobs had Gutierrez move in and live on the property for 90 days, he said.

Gutierrez started working for Jacobs after a mutual connection told him the company was looking for contractors with a background in the military. Based in the South Bay, Gutierrez said he hadn’t worked in a couple of years as he was dealing with PTSD, and was feeling a “void.” The squatter gig was up his alley, and he was immediately hooked, excited about helping, in his view, “to lay the foreground for a whole new industry.”

“I understand that the homeless population is tremendously high and the amount of vacant homes per homeless person is ridiculously high too,” he said. “Are they wrong for just trying to survive and have basic shelter? No. But I think it falls back onto society and lawmakers and politicians for not addressing it and providing a solution.”

The Adeline duplex is now on the market. Credit: Natalie Orenstein/The Oaklandside

The Adeline duplex is now on the market. Credit: Natalie Orenstein/The Oaklandside

Jacobs said he worked in property management for a number of years after studying business in college. He managed apartment complexes and frequently had to deal with squatters.

“It was a learning curve process,” Jacobs said. “How can I get people out, and how can I do this legally? I ended up getting pretty good at it.”

He began offering squatter removal services on the side, which he did for several years until he quit his job and turned the squatter work into a full-time enterprise. He says he’s built up a clientele of both individual property owners and corporate landlords, and claims to have about three dozen contractors he calls on to help with the properties — both residential and commercial sites. He’s filmed some of his team members in videos he posts, installing boards on windows.

When Jacobs takes on a job, he and his contractors sign temporary leases with the property owner.

This move is his secret weapon.

Jacobs is a big fan of California’s “castle doctrine.” The state law says someone has no duty to retreat in defending themselves against an intruder in their home. They can legally use force, even deadly force, to protect themselves — so long as the force used is proportionate to the threat.

Without the castle doctrine, “I’d be out of business,” Jacobs said. “It’s saved my ass.” Because he always signs a lease for the properties where he’s working, the home is legally “his,” Jacobs asserts. And as a legal occupant, he can enter it and use force to defend against “intruders” — squatters.

Flash Shelton, a prominent figure in the industry who goes by the moniker Squatter Hunter and has a TV show on A&E, also uses and encourages the strategy of becoming a legal tenant at a property.

By leasing up at the property, Jacobs is “turning the tables, very appropriately and sophisticatedly,” Pigott said.

Asked how he contends with the fact that his work can lead to people getting harmed, Jacobs fervently justified his approach, saying he only uses force in self-defense.

“We’re not gun-happy. Why do police do their jobs and put their lives on the line? Somebody has to,” he said.

“If you don’t believe in what you do,” he continued, “is life worth living?”

Guns versus swords

Jacobs treats many of his tactics as trade secrets, for obvious reasons. He doesn’t want the people he uses them against to know what to expect. But he’s happy to give hints about the unconventional strategies he employs.

“We’re the only company that uses swords — we love swords,” he said.

There’s a photo on the ASAP Squatter Removal website of Jacobs, long hair tied back and eyebrows furrowed in concentration, wielding a sword in one gloved hand and grasping a grenade with another.

In several videos he’s posted, he carries what he calls a spear — two blades attached to the end of a titanium golf club.

The old-school weaponry is a “less-lethal” approach, Jacobs explained, and one that his opponents rarely know how to defend themselves against. “I’m recently training all my cadets in melee weapons.”

He also uses shotguns and assault rifles.

“We have a lot of gear we use too,” Jacobs added. “Body armor is number one.”

And military gas masks. Why? Because he also uses smokescreens and tear gas.

Then there are the long-range acoustic devices, which are traditionally used to communicate across large distances.

“You can annoy them at night,” Jacobs said about blasting extremely high-decibel sound into buildings. “They can potentially cause short-term psychosis. That’s a great tactic for getting people out of the house safely.”

Sometimes, according to Jacobs, ASAP Squatter Removal will get hired for a surveillance-only gig. In those cases, he said, his crew will often go undercover — say, as a guy jogging by the house who will stop to “flirt with the squatter” to acquire intel.

“One time I was dressed up as a homeless meth addict” in front of a squat, Jacobs recalled, “and a guy came up to me and asked me to watch their place for a few hours. I was like, ‘Hell yeah.’ Next, I’m in there boarding up the property, throwing their stuff out.”

Jacobs said he warns all the people he hires on contract about the dangers inherent to the work, and has them wear body cameras. The job application online leads with a cautionary note: “Every job comes with real risks — you could get injured, killed, or arrested.”

“I constantly tell my guys, ‘Hey, try and make sure you’re not gonna kill someone,’” Jacobs said. Castle doctrine or no, “you’re going to get arrested.”

Jacobs has a bone to pick with how the police, courts, and California as a whole handle squatters. The state should strive for a system like Florida’s, he said. A recent law there requires sheriffs to immediately remove illegal occupants reported by landlords, instead of compelling property owners to pursue a longer eviction process.

In Alameda County, a property owner can file an eviction lawsuit after giving notice to a tenant or occupant. If the occupant fails to quickly file an answer to the lawsuit, the landlord wins by default. If they do respond, the case continues, often for months. The vast majority of lawsuits are settled out of court, but in cases that go to trial and result in a landlord’s victory, sheriffs will carry out an eviction.

Jacobs feels this lengthy exercise makes money for the government but is less effective than his brute-force move-ins.

“I really disdain our legal system,” he said.

All eviction cases in Alameda County are heard at the Hayward Hall of Justice. Credit: Amir Aziz/The Oaklandside

All eviction cases in Alameda County are heard at the Hayward Hall of Justice. Credit: Amir Aziz/The Oaklandside

A longtime tenant attorney we interviewed has a different view. Peter Selawsky of the Eviction Defense Center in Oakland said the system can be sluggish, but it’s designed to support landlords in removing tenants or squatters who shouldn’t be living at their property. Despite the bureaucratic procedures that frustrate both sides, eviction court actually goes much faster than other civil processes, Selawsky noted, including because tenants don’t usually have the right to counter-sue the landlord.

“People’s frustration with the legal system doesn’t mean the other side in their case doesn’t have legal rights,” Selawsky said. “It’s a system designed to give landlords their property back. The idea that they can’t even have that, and have to resort to some sort of vigilante justice outside the system, from the perspective of tenants and their advocates, it’s outrageous.”

It’s up to the court, Selwasky said, to determine who is a tenant and who is a “squatter.”

Sometimes Jacobs’ ire is also turned on the property owners — especially those who try to trick him into forcing out rightful tenants.

One time, a landlord illegally turned off her tenants’ water and changed their locks, claiming they were squatters because she wanted them out, said Jacobs, who voided the contract.

“When you get hired by the client,” he said, “you’re only hearing one side of the story.”

A former squatter steps out of the shadows

RCA, an infamous former punk squat later slated for redevelopment, is part of Oakland’s long history of squatting. Credit: Amir Aziz

RCA, an infamous former punk squat later slated for redevelopment, is part of Oakland’s long history of squatting. Credit: Amir Aziz

Christine Hernandez first squatted about a decade ago.

Her family was forced to leave their Oakland home and set out to find a new rental. But this was the mid-2010s, and they were immediately confronted by the realities of the housing crisis, where East Bay rents had reached an astonishing apex. Even with two working parents, the family of six couldn’t find anywhere affordable.

So they moved into an old abandoned drug house in Fruitvale. There was no plumbing or appliances; they installed them. The place was a wreck: they painted the walls and planted a garden.

During the family’s tenure there, they linked up with Steven DeCaprio, who specialized in helping people pursue adverse possession — a.k.a. squatters’ rights.

Under California law, squatters must take a number of steps to have a shot at legally claiming ownership of a property. The essential task is to openly occupy the property for five years and pay property taxes. In the meantime, they’re never secure where they’re staying. At one point, the bank sent a company to change the locks and shut off the water and power at the place Hernandez’s family was living. They also let their dog loose.

When we prioritize somebody’s passive income over life, we have a problem.

-Christine Hernandez

Hernandez, now the director of resident empowerment at the Sustainable Economies Law Center, never got ownership of the Fruitvale house and doesn’t squat anymore. She lives in a big, communal Victorian in East Oakland that’s owned by a land trust and run cooperatively by tenants.

Hernandez has publicly shared her family’s squatting story often. That’s an intentional choice.

“This narrative about ‘all squatters are bad and engaged in illicit activity in properties’ is why my family was willing to not do this in the shadows, but to come forward,” Hernandez said during a recent interview. “There are so many people [squatting] who are unhoused, but they’re just invisible. That’s because you’re fearful of CPS calls or other things that might compound the suffering and challenges you’re already experiencing.”

It wasn’t a romantic lifestyle. Her Fruitvale squat was in a high-crime area where a bullet flew through the window and almost hit her teenage daughter. But people living on the streets face a mortality rate that’s four times higher than housed people, for all sorts of reasons.

“When we prioritize somebody’s passive income over life,” Hernandez said, referring to speculators and landlords, “we as a society have a problem.”

At last estimate, about two-thirds of Oakland’s 5,500 homeless people were unsheltered, living in tents or vehicles, or even more dangerous circumstances.

The Moms 4 Housing movement sought to shine a light on the dissonance between the homeless population and real estate speculation. A group of unhoused mothers took over an investor-owned property in West Oakland in 2019. After a forceful sheriff eviction and big protests, the city eventually facilitated the sale of the corporate-owned home to a local land trust.

Squatters often intentionally occupy buildings or land on the county’s list of tax-defaulted properties — those where the owner hasn’t paid taxes for at least five years.

The city has tried to pressure property owners into renting or selling their vacant homes to unlock more housing for residents. In 2018, Oakland voters passed a flat tax on vacant properties — $6,000 a year for residential buildings. But it’s unclear whether the tax has worked as an incentive.

Facing off across a fence

In one shaky phone video posted to ASAP Squatter Removal’s Youtube page, Jacobs confronts a man whom he accuses of trying to break into a property where he’s working.

“Why are you trying to get in here?” he asks a guy on the other side of a chain-link fence.

“Why are you in there?” the man responds.

“Why does it matter to you?” Jacobs says.

“Why does it matter to you, same thing?” the man retorts before walking off.

After he leaves, a flustered Jacobs talks to himself, cursing about the encounter. He says people try to break back into squats “all the time.”

This 30-second interaction — a late-night confrontation between a potential trespasser and a guy essentially hired to squat in order to ward off squatters — is a microcosmic display of tensions between some of the largest institutions that shape how all of us access and use housing.

In a city where thousands don’t have a permanent place to sleep at night, where courts are clogged with cases, where corporations are increasingly buying properties, where residents are drowning under some of the highest rents and house prices in the world, where landlords are reeling from loss of income during COVID, and the city government is limited by a fiscal crisis, it’s not surprising that vigilante operations have emerged to try and solve or exploit — depending on your view — the desperation.

Jacobs says he’s the only squatter remover active in Northern California. But most of the similar companies incorporated in the state popped up in just the past few years, indicating this field could grow.

For now, though, Jacobs, his crew, his combat weaponry, and his cat — who travels with him from squat to squat — seem to have become the go-to company for the region’s frustrated property owners, boarding up homes from Sacramento and the hills of San Francisco to the flatlands of Oakland.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the COVID-19 eviction moratorium in Oakland made removing squatters through the court process temporarily illegal. However, the court process for removing squatters and trespassers, known as forcible detainers, was allowed under the COVID-19 eviction moratorium.

“*” indicates required fields