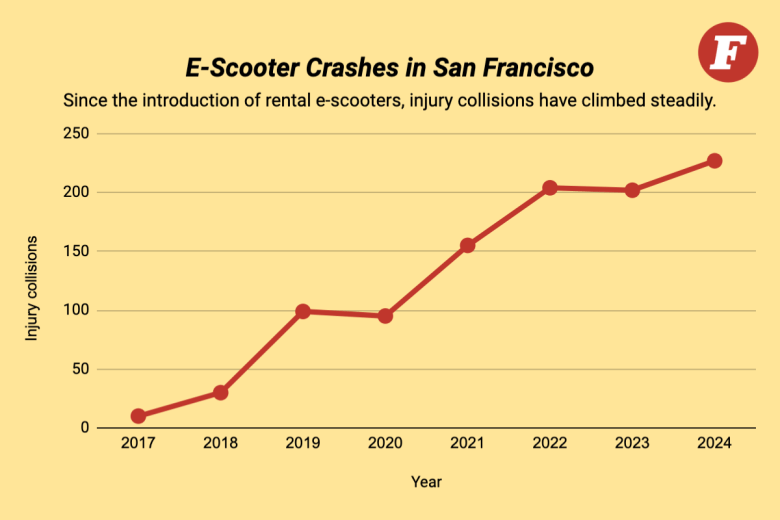

San Francisco has a painful scooter problem. The electric devices are driving a sharp increase in injury crashes. They’ve gone from zero a decade ago to 227 in 2024.

Rental e-scooters arrived on SF streets in 2017. What the SF Municipal Transportation Agency calls “standup powered devices” now account for 6 percent of all injury crashes on city streets.

Those are the data. There are stories, too, such as the death in July of a 77-year-old pedestrian who was struck crossing Market Street. Two years earlier, a 55-year-old Dutch tourist died of injuries after he was struck by an e-scooter rider, also on Market.

There have been local and state efforts to curb the danger. For years, California law has capped scooter speeds at 15 mph, banned them on sidewalks, and required riders to have a driver’s license.

Lime and Spin, the companies licensed to rent e-scooters in SF, can limit device speeds and conduct license checks when customers sign up. Their scooters also have sidewalk-detection technology. But private scooters, a growing category, are another matter.

As SF officials search for answers, others have taken more drastic measures. New York City is about to impose a 15-mph limit. Paris voted to ban the rental companies altogether.

For now, SF seems mostly intent on encouraging e-scooters to join bikers in protected lanes and stay out of traffic.

A new problem

E-scooters entered the SF scene in 2017 when companies began scattering their devices across city sidewalks without permits. The rollout was rocky and chaotic; after a few weeks, SFMTA stepped in to create permits and pilot programs.

Eight years later, e-scooters and e-bikes seem ubiquitous, especially as private ownership has skyrocketed. Nationwide, e-scooter injuries increased 45 percent each year from 2017 to 2022, according to UCSF researchers.

In San Francisco, e-scooter ridership jumped 55 percent from 2020 to 2024, according to Ride Report’s Global Micromobility Index. Collisions have jumped too, as SFMTA reported in August — both solo crashes and collisions with other people.

Injuries involving “stand up powered devices” accounted for 6 percent of all injury crashes on SF streets last year — a number that’s been steadily climbing since 2017. (Source: SFMTA, The Frisc)

Injuries involving “stand up powered devices” accounted for 6 percent of all injury crashes on SF streets last year — a number that’s been steadily climbing since 2017. (Source: SFMTA, The Frisc)

Rutgers University researcher Hannah Younes says part of the problem is inexperienced riders. “When new users gain more experience, the collisions go down,” she tells The Frisc.

As more people get on scooters for the first time, other cities haven’t had much patience.

To e-scoot, or not to e-scoot

Paris first saw scooters, rented via an app, in 2018. But the City of Light made a u-turn in 2023, when 89 percent of voters elected to ban them. One caveat: turnout was less than 8 percent. (Privately-owned e-scooters are still permitted.)

Washington, DC took a different route. The nation’s capital quickly built bike lanes earlier this decade, which encouraged more scooter riders, according to a Lime report. Bikers also reported a 39 percent drop in crashes over the same period.

Seen in 2024, a scooter rider cruises down the new 17th Street bike lane in San Francisco. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Seen in 2024, a scooter rider cruises down the new 17th Street bike lane in San Francisco. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

“If you build more bike lanes, injury rates decline,” says former Lime policy research leader Calvin Thigpen, one of the report’s co-authors.

New York City is working the enforcement angle. This week, the city will impose a 15 mph speed limit on e-bikes and e-scooters. The move has stirred debate over how to incorporate new devices into Big Apple traffic, as well as how to enforce new rules. An Aug. 7 Wall Street Journal story points out that e-scooters and e-bikes aren’t equipped with speedometers, nor do they have license plates or require registration, which makes passive enforcement (such as speed safety cameras) useless.

Meanwhile, e-bikes are getting more powerful, prompting a new wave of California laws. One law bans modifications that make e-bikes go faster, and another bans sales of Class 3 bikes to kids under 16. Another law allows police officers to confiscate “moped-style” bikes, which can go faster than the legal e-bike limit of 28 mph.

All of these devices, regulated or not, have changed how street traffic flows.

Can we build our way out of the problem?

The rapid rise in crashes shouldn’t distract us from the real menace, says one sustainable transit researcher.

Dillon Fitch-Polse, co-director of the BicyclingPlus Research Collaborative at UC Davis, says e-scooter injuries are an issue, but “speeding cars are far more dangerous, and we should be doing everything we can to reduce car speeds.”

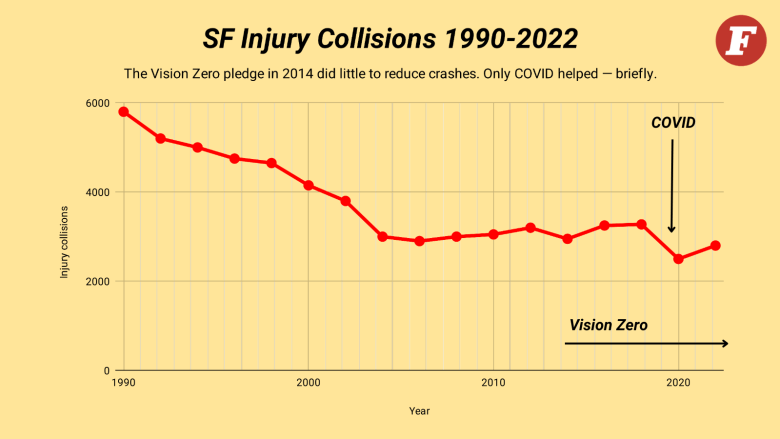

Speeding was the chief cause of collisions resulting in injuries and deaths between 2020 and 2024 in the SFMTA report. Of 13,744 people injured in collisions, 47 percent were vehicle drivers and passengers, while 22 percent were pedestrians. Of the 164 fatalities in that same time period, pedestrians accounted for more than half.

Injury collisions involving cars have remained steady since the mid-2000s (dropping only during the pandemic), with speed a primary cause. (Source: SF OpenData, The Frisc)

Injury collisions involving cars have remained steady since the mid-2000s (dropping only during the pandemic), with speed a primary cause. (Source: SF OpenData, The Frisc)

The city has crafted full-scale street overhauls as well as lighter touches, such as corner bulb-outs and bike lanes marked with plastic posts and paint. Still, injuries have hovered around 3,000 a year since the mid-2000s, except for a brief dip at the start of the pandemic.

SF is now turning more to tech, with speed cameras at 33 locations across the city. Initial early reports are promising, showing a 72 percent reduction in speeding at 15 sample locations over September.

But slower cars might not solve a key issue: keeping everyone in their lanes — especially the newer riders.

SF Bicycle Coalition director Christopher White says new e-scooter users might not know that they should ride in the bike lane. (Photo: Taylor Barton)

SF Bicycle Coalition director Christopher White says new e-scooter users might not know that they should ride in the bike lane. (Photo: Taylor Barton)

In his previous research for Lime, Thigpen found 40 to 50 percent of trips taken on rented e-bikes and e-scooters replaced walking. Some number of those riders are newbies.

In making that switch, people don’t always know where to go, says San Francisco Bicycle Coalition executive director Christopher White: “Riders may not know they belong in the bike lane, and some cyclists don’t know that scooters belong in the bike lanes.”

Safer shared lanes, which have seen some success in DC, are one of SF’s main goals.

“From the traffic engineering standpoint, we’re committed to keeping all road users safe. For e-bikes and e-scooters, this means providing infrastructure like bicycle facilities, traffic signals, and other signage (yield, speed limit) to make sure that there’s separation between the various modes of travel,” says SFMTA spokesperson Michael Roccaforte.

While scooters crashes are up, bike injury crashes are down 25 percent since 2019, according to SFMTA.

But bike-lane buildouts in SF, even with funding in hand, can be contentious, painfully slow, or both. SFMTA’s uncertain financial future has also stymied other street safety measures, like speed bumps on residential streets.

More budget cuts could be coming. Last month, SFMTA’s chief financial officer called on divisions to cut 5 to 7 percent as the agency waits for a state rescue loan and hopes that voters in 2026 approve higher taxes for funding.

The Bicycle Coalition’s White says agency cuts also hit an education program that would have taught new e-scooter riders how to ride safely in the city.

Complicating the issue even more is the divide between shared and privately-owned e-scooters. Lime and Spin’s city contracts require them to use technology that essentially forces riders to follow the law. But “you can’t enforce these restrictions on privately-owned devices,” says Rutgers researcher Younes.

SFPD did not respond to multiple requests for comment about enforcement of traffic laws for e-scooter riders. Roccaforte says that regulation of privately-owned devices is not in SFMTA’s purview: “It’s done at the state or federal level.”

White has his own first-hand experience. Riding his bike on Market Street on election night last year, he saw someone on a private e-scooter crash into a Bay Wheels bike rack. The impact smashed a couple of the docking stations and apparently broke the rider’s leg. (White called an ambulance.)

The sale of non-street-legal devices, he says, are “contributing to an atmosphere where people don’t feel safe.”

More from The Frisc…