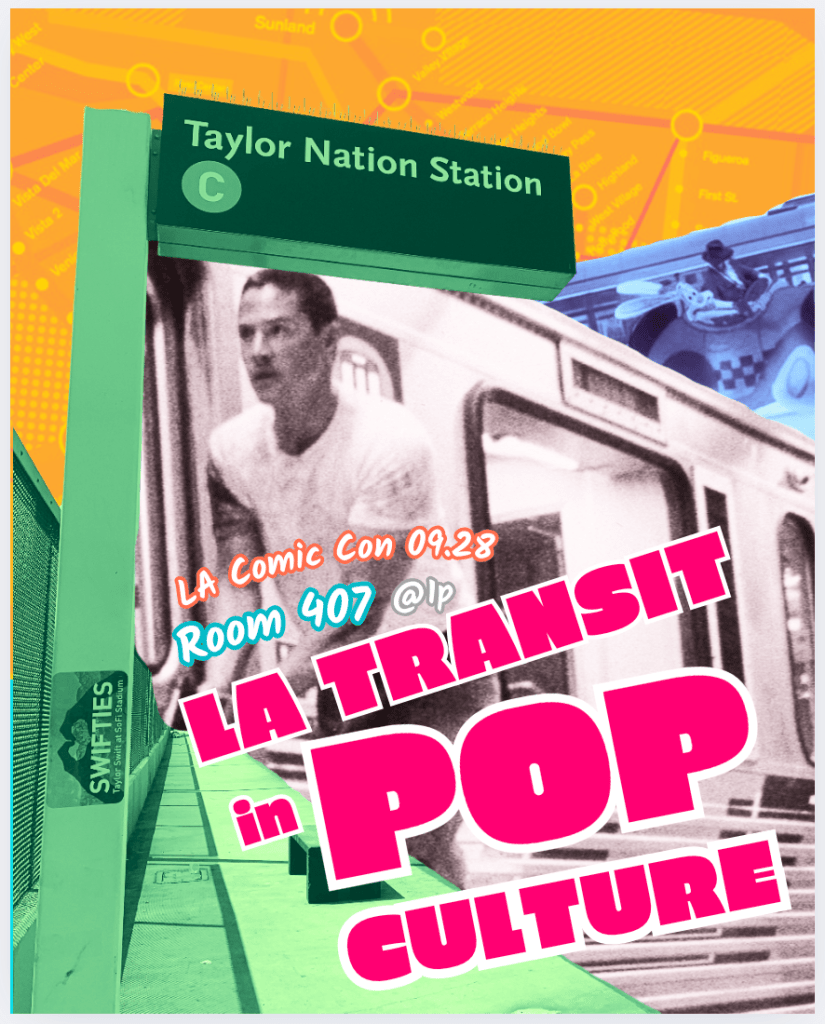

On 28 September, Nobody Drives in LA‘s co-hosts and friends-of-show — Eric Brightwell, Ivy Kwok, Kyle Rebar, and Rogelio Pardo — hosted a panel at LA Comic-Con called LA Transit in Pop Culture. It was filmed by past-guest and friend-of-the-show, Alex Denney. Rogelio talked about Missing Persons‘s radio staple, “Walking in LA” and how it affirms classist and racist ideas about people who don’t exclusively drive. Ivy talked about the renaming of Metro stations after pop culture figure and ways pop culture can raise awareness and positive associations around mass transit. Kyle shared Metro ads featuring Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Super Kind; moderated the whole affair — and did most of the technical work.

Kyle also made the art, which visually referenced a movie about a bus that couldn’t slow down. I think it was called The Bus That Couldn’t Slow Down.

If you weren’t able to make it, we’ve got you covered.

If you want to read the essay my section was adapted from:

Science-Fiction films’ speculative depictions of transit in the future Los Angeles, whilst at least generally superficially forward-thinking, also inevitably reflect the biases of their creators. They are usually Los Angeles as seen through the lens of the wealthy white gaze – and the tinted windshield of a luxury automobile. As a result, these films invariably fail to capture the city’s increasingly multicultural and multimodal direction. Our mass transit is, after all, where that reality is both most on display and where forward-thinking imagination is most required.

Before we return back to the future for inspiration, though, let’s briefly return to our past – to the first film shot in Los Angeles. 1897’s straightforwardly-named South Spring Street, Los Angeles, Cal. (1897), filmed by Frederick Blechynden. It’s not science-fiction, and yet the vibrant streetscape it captures is something we can only dream of in our car-brained present – except during open streets events like CicLAvia, where cars are briefly removed so that the streetscape can temporarily thrive. It is a movie, although in the language of the time it was known as an animated photograph. Its caption reads “Various equipages pass, including a tally-ho and six white horses. A peculiar, open-end trolley car comes along; bicycle riders and pedestrians” — a description that takes nearly as long to read as the movie’s 25-second run time – but somehow manages to say it all.

Now let’s turn to the future. The year? 2019. The film? Blade Runner. It’s one of my favorites but neither I nor anyone else would likely describe it as flawless. There’s perhaps no bigger critic than its director, Ridley Scott, who was seemingly pathologically compelled to tinke with it. Then years after its theatrical release, he released his Director’s Cut. 25 years after that, he was back again, with the Final Cut. To date, there are at least seven publicly available versions.

Blade Runner is more often characterized as a Los Angeles film than a transit one. However, while it incorporates several Los Angeles landmarks, including the Bradbury Building, the Ennis House, and Union Station — it’s primarily a studio-bound affair, created, by and large, on a Burbank backlot. On the other hand, one of its most memorable innovations is its flying cars, called spinners.

A lone Spinner over a Los Angeles with 109 million inhabitants

A lone Spinner over a Los Angeles with 109 million inhabitants

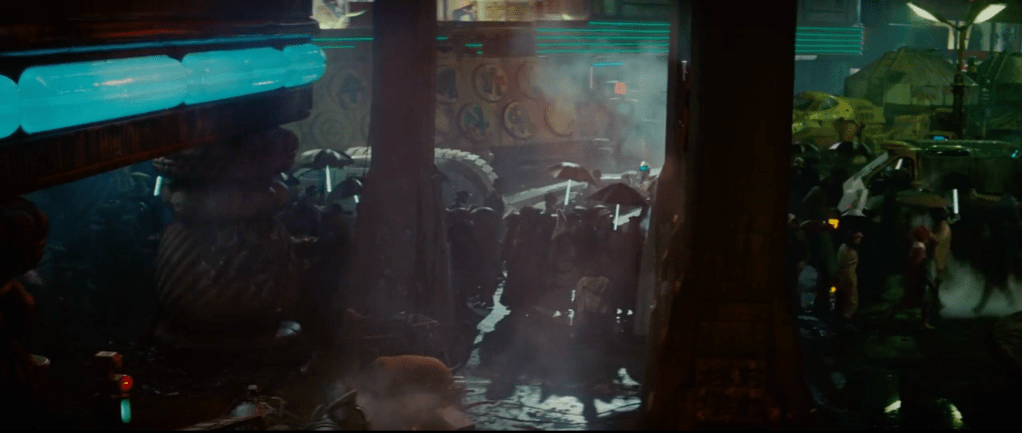

The focus on spinners overshadows the fact that the future transit of Blade Runner is, in fact, surprisingly multimodal. Notably, there are seemingly never more than four spinners in the sky at once – hardly making them the dominant form of transit in a metropolis of 109 million. Interestingly, spinners don’t appear at all in Philip K. Dick’s source novel, but seems to have been invented for the film primarily to bolster its hard-boiled detective and neo-noir vibes – genres that thrived in the 1930s and ‘40s, when flying cars were most common in science-fiction.

A crowded Los Angeles sidewalk in the rain

A crowded Los Angeles sidewalk in the rain

Deckard hanging on the side of a bus

Deckard hanging on the side of a bus

But in Blade Runner’s future Los Angeles, there’s also an elevated railway. In a single shot, seventeen cyclists pass through the frame. And even though the streets are soaked with rain, they’re always crowded with throngs of Angelenos. Nevertheless, the future-minded commercial media still continues to focus on flying Ubers rather than noodle stall density for our consumerist needs. Electric sheep dream of androids.

Whilst the Angelenos of Blade Runner are diverse by Hollywood’s impossibly low standards, they barely begin to approach the diversity of reality. The fact that Blade Runner is so remembered for its Japanese influences is a reflection of both the Westerner’s envy and anxiety regarding that country – which seemed for so many in the ‘80s to embody the future. In reality, though, there are only two Japanese actors in the film. One plays a Cambodian, the other a sushi chef. The diversity doesn’t end there, though. The famous geisha in the advertisement is portrayed by a Korean. Mexican American actor, Edward James Olmos, plays a character named Gaff, who speaks CitySpeak – a hybrid of Spanish and Japanese, naturally, but also French, German, and Hungarian – languages that aren’t exactly part of the Los Angeles lingua franca. Surely if we ever evolve a form of CitySpeak here, it will be less linguistically European and include, instead, bits of Mandarin, Tagalog, Armenian, and Korean. Maybe that’s something only an Angeleno who takes public transit would realize. Finally, whilst the cast of Blade Runner was 70% white, the Los Angeles of 2025 is more than 75% not.

It’s now been ages since Blade Runner was released. I think it was Thom Andersen in Los Angeles Plays Itself who said that the more time passes, the less the film seems to be about the future and the more it plays like a documentary about the ‘80s. He also referred to it as “the official nightmare of Los Angeles” — but, for me, it’s close to utopian for all the things it gets right. My official nightmare of Los Angeles is as relentlessly sunny as Blade Runner is dark and rainy – and depicts a Los Angeles that is far more homogenous from both a class and ethnic standpoint. It’s also, in its way, just as much a documentary about the anxieties of its era – in its case, the early 21st century – as Blade Runner was about the late 20th. That film is 2013’s Her, directed by Spike Jonze.

Like Blade Runner, Her reflects the concerns of a privileged Westerner for a perceived Asian economic rival. In the case of Her – and in the mind of the modern American paranoiac – that rival is China. China today, like Japan in the ‘80s, inspires a mix of both envy and anxiety in American audiences. After all, China can seemingly conceive and execute large-scale projects in less time than it takes a Western developer to locate a pair of giant scissors or a golden shovel. We tend to brush aside the social and environmental costs; the inorganic, top-down planning; the hyper-functionalist zoning, and even China’s worsening car-dependency. Who cares? China has more high-speed rail than the rest of the entire world – isn’t that all that matters?

While today Her is mostly remembered as a love story between a dork and an AI, at the time of its release, much of the local media focus was on its depiction of transit in a car-free Los Angeles. Unable to find anywhere sufficiently futuristic within Los Angeles, the cast and crew of Her filmed for two weeks in Shanghai. Within Shanghai, they chose the Pudong District, an area that the Party Central Committee and the State Council decided to modernize, from the top down, in 1990 – mainly by constructing a network of elevated pedways. Her makes such ample use of these pedestrian walkways, in fact, that many critics mistakenly described the Los Angeles that it depicted as car-less. In reality, though, the cars are just below – on streets where bicycles are largely banned and, presumably, most of the amenities people want to take advantage of are actually located. You can actually see cars in several frames – usually somewhat hidden, out-of-focus, and out-of-mind – just like the film’s huge uncredited cast of Chinese extras.

Someone should’ve told the crew about the Calvin S. Hamilton Pedway, built much closer to home in Los Angeles’s Bunker Hill and Financial District in the 1970s, back when Western planners thought transit mode segregation was the future. Today that system is generally quite desolate – used mostly by those who walk mostly for exercise and not to actually get anywhere. The streets below, like Figueroa, meanwhile, are hostile – dominated by cars and as utterly unhappening as anyone who actually walks would expect.

For me, the most appealing scene in Her is the one that is most connected to the past – the Tang and Song dynasties, to be precise. That’s the night market scene filmed not in Pudong but in the slightly older Wujiaochang district. It is the scene in which one of the only Asian actors in the film gets a line – “you want a Coke with that?” But it’s also a past the wrongheaded officials have since mostly erased. Chinese planners, in their infinite wisdom, have shut down most night markets in the past few years, dismissing these vibrant outdoor eventspaces as embarrassing reminders of a less prosperous past. The Party feels strongly that the future is to be found in ‘80s-style mall food courts. I wouldn’t be surprised if Jonze agrees.

Is it surprising that Jonze’s vision of the future Los Anglees is different from that of a car-free, working class Angeleno? After all, Jonze grew up in a wealthy east coast family and, when he moved to Los Angeles bought a home in an area of the Hollywood Hills with a walkscore of 11 out of 100. By his own admission, Her’s aesthetics were influenced not primarily by either Japan or China, but that old time mall food court staple, Jamba Juice – a chain I wrongly assumed didn’t survive Y2K. Whilst Jonze may’ve opted for a car-dependant neighborhood, there is a Jamba, as I learned the chain is now known, just 23 minutes away on a Metro bus – but does anyone actually think that Jonze’s Los Angeles transit vision is informed by anything other than his view from his multiple homes and from within a car? Do you think, in other words, that he’s ever walked in Westlake or biked in Boyle Heights?

With Her, what wasn’t filmed in China was filmed in Los Angeles — where Asians are the largest “racial” minority and where there are more Cambodians, Filipinos, Iranians, Koreans, Taiwanese, Thai, and Vietnamese than anywhere else outside of their respective home countries – and yet not one of whom appear in the film. In fact, the combined dialog of Asian American characters in Her adds up, across the entire film, to just 21 seconds – less than the entire running time of South Spring Street, Los Angeles, Cal.

Theodore Twombly walks past an expanded Metro rail map

Theodore Twombly walks past an expanded Metro rail map

Nevertheless, upon its release, Her was championed amongst many white urbanists for its supposedly progressive portrayal of transit. When I saw it in a Los Feliz cinema, the crowd cheered – not without cause – when they saw the imagined and greatly expanded Los Angeles rail map. They cheered, too, when the wealthy white protagonist emerged in unfortunate sweatpants from his train station at a beach in the South Bay. Writers at Gizmodo, KCRW, LAist, the Los Angeles Times, and other outlets all gushed over the film’s depiction of imagined public transit to the beach… even though, by then, public transit had provided beach access for 139 years… and even though the very first Metro train, which began service in 1990, terminated in Long Beach, a town which rather famously has a beach, and, famously, a long one at that. But actual mass transit users knew, implicitly, that for these articles’ white writers, “public transit” means trains, not buses – and “beaches” mean those on the Westside and South Bay – not the working class Harbor Area.

Does it really matter, though, if wealthier white car-brains are the only ones behind the wheel of our collective imagination? These are just films after all, right? They’re just entertainment, no? If only. In reality, science-fiction has always profoundly informed and influenced the transit-sphere. If you don’t include working class Angelenos in the conversation; talk inevitably turns to expensive and hairbrained tech solutions like Tesla Tubes, aerial trams, and DoorDash Drones when what the present and future really demand are simple and sustainable solutions like street trees and bus lanes. And if people of color exist only in your blindspot, you get transit in Hollywood panels where all of the panelists are white and most drive. In a city this big and diverse, it’s not a big ask to include, listen to, and learn from working class and/or non-white Angelenos. Most Angelenos are working class, after all – and in addition to the aforementioned groups – Los Angeles is the city with the largest diasporic communities of Armenians, Belizeans, Guatemalans, Mexicans, and Salvadorans. If you look around and all the faces look like yours and all the voices you hear sound like yours, you’re in a bubble and you’re damn sure not on the bus!

TRAILERS AND VIDEOS

Blade Runner (dir. Ridley Scott, 1982)

Her (dir. Spike Jonze, 2013)

Joanna Wang‘s rejected demo for Metro’s Super Kind PSA

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ SCRTD Metro Blue Line PSA campaign 1990

Nobody Drives in LA Autumn 2025 Meet-Up

South Spring Street, Los Angeles, Cal. (dir. Frederick Blechynden., 1897)

Taylor Swift‘s “Delicate”

Volcano (1997, dir. Mick Jackson)

LINKS

Fahrenheit-182 by Dan Ozzi and Mark Hoppus

Los Angeles, the City in Cinema (dir. Colin Marshall, 2013)

Los Angeles Plays Itself (dir. Thom Andersen, 2003)

My Life as an Architect in Seoul by Byoung Cho

Pacific Railroad Society Museum

Riding the Rails: Tourist Guide to America’s Scenic Train Rides by William C. Herow

T00b N00b Gr00p R1d3

Transit and Hollywood: Telling the Story that Moves Us

We Are Legion (We Are Bob) by Dennis E. Taylor

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between, that he hopes to have published. If you’re a literary agent or publisher, please contact him.

You can follow him on:

Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Threads, and TikTok.