Berkeley High School teacher Hasmig Minassian has already instituted a cellphone ban, requiring her students to place their devices in pouches each class period. Berkeley Unified is currently working on a districtwide policy, which must be in place by July 2026 to comply with state law. Courtesy: Hasmig Minassian

Berkeley High School teacher Hasmig Minassian has already instituted a cellphone ban, requiring her students to place their devices in pouches each class period. Berkeley Unified is currently working on a districtwide policy, which must be in place by July 2026 to comply with state law. Courtesy: Hasmig Minassian

How much should students be allowed to use their cellphones at school, and how should the rules be enforced? Those are the central questions facing Berkeley Unified School District (BUSD) as it grapples with updating its mobile-device guidelines to adhere with a new state requirement.

This story was written in partnership with the Berkeley High Jacket, the student newspaper of Berkeley High School.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 3216, also known as the Phone-Free School Act, in fall 2024 to address the potential negative impacts of excessive cellphone use among teens, including reduced attention in classrooms. The law requires all school districts in the state to limit or prohibit students’ use of smartphones, and imposed a deadline of July 2026 for them to develop and adopt policies.

California is one of 26 states with laws restricting or banning student cellphones at schools. Data on the effectiveness of cellphone policies on improving academic performance is limited. But one recent study in Florida found test scores improved in schools that enforced cellphone bans, after an initial adjustment period.

BUSD’s current policy allows students to use mobile devices on campus during non-instructional time. The district’s updated policy, which is still in the draft stage, is more specific: It would require students in all grade levels to turn off their smartphones and mobile devices during instructional time, while imposing stricter rules for younger students.

Specifically, students in preschool through fifth grade would be required to power off their mobile devices during the entire school day. Sixth through 12th grade students, who are much more likely to have their own devices, would only need to shut them off during instructional time. Students would not be prohibited from possessing or using a mobile device during emergencies or threats, while under a physician’s guidance, or if access to a device was part of an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

BUSD Superintendent Enikia Ford Morthel said during a recent school board meeting that the updates are intended to improve on the district’s existing policy — which she said was created in 2024 with community input — by clarifying expectations for students and educators and providing more guidance on how to apply the rules.

“I think we all agree babies of all ages should not have [smartphones] during instructional time,” Ford Morthel said. “Now it’s about: How do we engage folks to have a really thoughtful implementation, considering costs and not adding an extra burden to our educators?”

Some teachers already ban cellphones in class

Nicolas Stephens, a fourth grade teacher at Berkeley Arts Magnet Elementary School, said he doesn’t think the mobile device policy will have much of an impact at the elementary school level. “I could probably count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen kids with devices during the school day,” he said. “It’s not really very prevalent at all.”

Still, his classroom policy is to keep mobile devices in backpacks during class. He said smart watches are fine to have, unless students use them to play games. He tells parents that electronic devices will need to be kept at home if they become distractions in class, but has yet to experience that.

“Middle and especially high school students are texting each other and they’re on social. Eight- or 9- or 10-year-olds are still getting used to interacting with each other in real life,” he said.

Nearly 25% of kids in the U.S. have a personal smartphone by age 8, according to a 2025 report by the nonprofit Common Sense Media.

You can put as many policies in place as you want, but if someone’s not enforcing those policies with consistency on a day-to-day basis, then those policies are not going to be strong.” — Hasmig Minassian, Berkeley High teacher

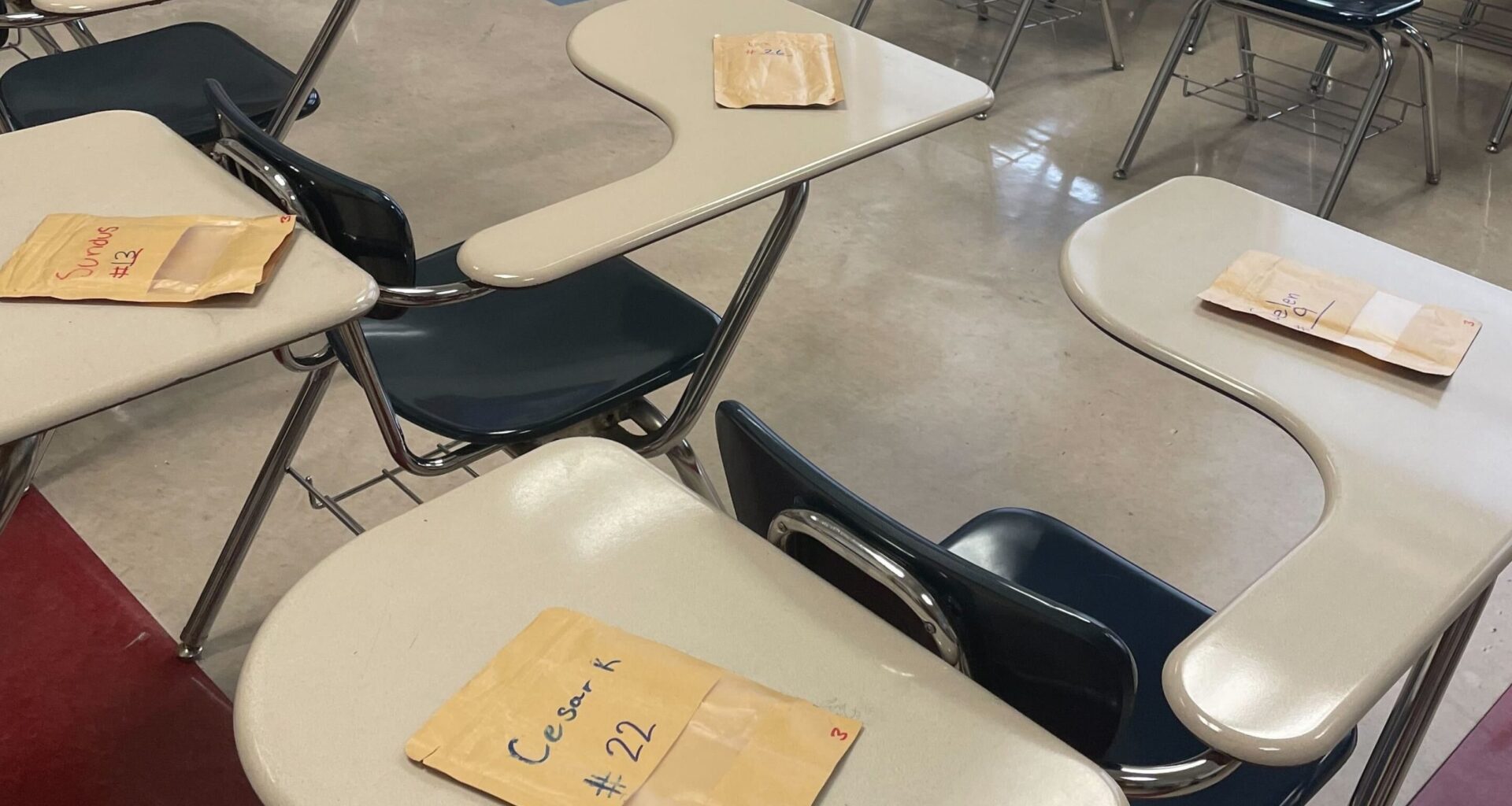

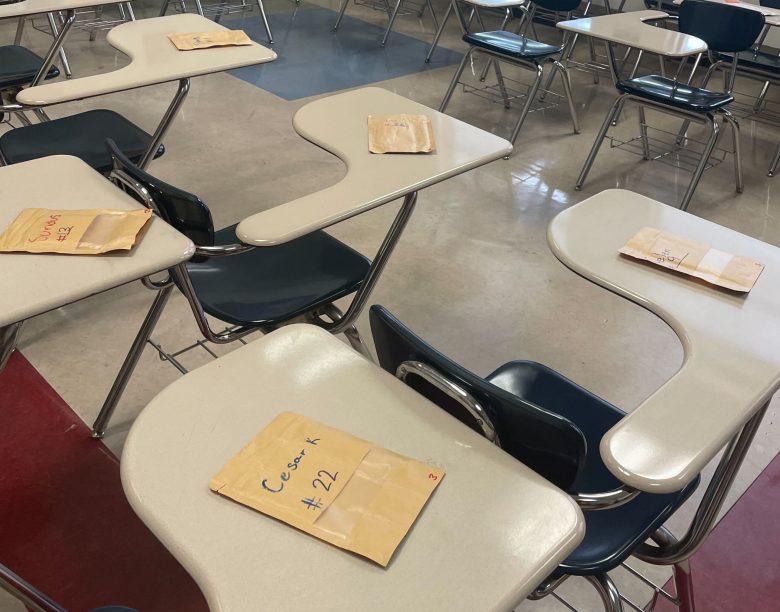

Hasmig Minassian, a Berkeley High School ethnic studies teacher, already has a cellphone ban in her classroom. Minassian is the co-teacher lead of the universal ninth-grade program at BHS, which has had a phone-free policy in place for eight years.

Every class period, her students find pouches with their names on their desks. They place their phones in the pouches, then hang them on a number chart, which is how Minassian takes attendance. “I wasn’t even aware that BUSD was putting a policy together because we didn’t really wait for anybody to tell us to do it,” she said.

In her classroom, students are only allowed to use their phones for medical reasons, during emergencies like fire alarm evacuations, and when they use the bathroom. Minassian said having cellphone rules in the ninth grade has helped set a precedent for higher grade levels, but questioned how well the policies will be implemented across the district.

“You can put as many policies in place as you want, but if someone’s not enforcing those policies with consistency, on a day-to-day basis, then those policies are not going to be strong,” she said.

In teacher Hasmig Minassian’s classroom at Berkeley High, students store their phones in pouches then hang them in numbered pockets, which Minassian uses to take attendance. Courtesy: Hasmig Minassian

In teacher Hasmig Minassian’s classroom at Berkeley High, students store their phones in pouches then hang them in numbered pockets, which Minassian uses to take attendance. Courtesy: Hasmig Minassian

BHS 9th grade teacher Jacob Disston has similar reservations. As the math teacher for Hive 5 — one of Berkeley High’s seven learning cohorts for incoming freshmen — his policy, made in agreement with other Hive 5 teachers at the start of the year, requires students to turn their phones in as they walk in the door. While this system has been successful, he said, there are inconsistencies with enforcement, even within the teacher group.

“Even with buy-in at the beginning of the year and everyone having the same [phone caddies], [the system] works differently because different teachers go at it differently,” he said.

The state says districts must engage communities on cellphone policies. Some parents say BUSD hasn’t done enough.

As it stands, BUSD’s current mobile devices policy can be interpreted loosely by teachers, with some choosing not to limit phone use at all. While the proposed guidelines would more clearly define when and where devices can be used, how to enforce the rules remains a gray area.

For example, according to the proposal, district employees could still choose whether or not to require students to turn in their devices at the start of class to “mitigate classroom disruption, applying the rule to students in a fair and equitable manner.”

“It’s frustrating because we really want to just focus our attention on teaching and learning,” Minassian said. “I don’t want to spend a lot of time with my colleagues talking about cellphones, but it is unfortunately one of the things that you have to [be in] lockstep with them or the whole thing falls apart.”

Berkeley High senior Oona Poirier said only three of her teachers actively enforce a phone ban. Poirier is not in favor of a complete ban on mobile devices, however.

“I wouldn’t be as focused because I wouldn’t have music [to listen to while working,” Poirier said. “I feel like it doesn’t factor in people who can be trusted with their phones.”

Disston said that although he’s “generally in favor” of a phone policy, the district should take care not to place the full burden on teachers. He said the policy’s success will ultimately be determined by “how we can partner with parents and the community.”

During the school board meeting on Oct. 15, BUSD parents and community members said they’d had no input on the updated mobile devices policy. One parent, Lindsay Nofelt, said it “does not necessarily fit the community needs” and asked for more opportunities to participate.

Nofelt had previously sent an email to district leaders on Oct. 14, which was shared with Berkeleyside, asking for more community engagement on the cellphone policy updates, as required by AB 3216. Language in the bill calls for “significant stakeholder participation” in the policy development process.

In her email, Nofelt shared the results of a survey she said she conducted over several days with over 100 other BUSD family members, gathering opinions on the district’s cellphone policy. In response to the question, “Do you think Berkeley schools have a good cellphone restriction policy?”, about 90% of those who took the survey replied “no,” and that more structure was needed, according to Nofelt.

“The previous engagement last year might have felt robust within the meetings, but it relied on people coming to the district a couple times, not BUSD seeking out opinion,” Nofelt wrote Berkeleyside about the district’s previous community engagement on the cellphone policy. In her email to district leaders, she suggested student-led research, more engagement with PTAs, and trying out pilot programs before adopting a permanent policy.

“Parents are right in calling it out,” school board member Ana Vasudeo said of the criticism during the board’s Oct. 15 meeting. “They want to understand how this is going to be implemented consistently throughout the district.”

District staff at the meeting proposed drawing on examples from other school districts, such as Los Angeles Unified, which began enforcing its cellphone policy in February of this year. According to early reports, LAUSD students have shown more engagement in school.

After the discussion and public comment, Ford Morthel said the proposal would return policy subcommittee for revisions, and that changes would focus on implementation and how to reduce the burden on educators.

Meanwhile, opinions among local students remain mixed.

Berkeley High sophomore Maximilian Wilhelm said that the commonly used solution at BHS of “phone caddies,” or receptacles where students drop their phones during class, “is already good enough… It should be up to the teachers if they ask students to put [their phones] in or not.”

Others hope that an updated policy will bring positive results.

“If we’re getting our phones taken away each period, I feel like it’ll help us be more focused in class, and a lot of grades will improve,” BHS sophomore Angel Arroyo Bernal said. “I feel like (the updated policy) will be really good for students.”

Co-author Penelope Purchase is a reporter with The Jacket, the student-produced newspaper at Berkeley High School.

“*” indicates required fields