Austin Baker and his team at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County are leading an ambitious effort to DNA-barcode every insect species in California as part of the statewide CalATBI initiative to “discover it all, protect it forever.”The project combines traditional specimen collection with modern genetic sequencing to build a comprehensive biodiversity library, revealing surprising hotspots of insect life—from foggy coasts to the species-rich Mojave Desert.By creating a genetic baseline of California’s insect diversity, the team hopes to track future ecological change, inform conservation priorities, and preserve the record of countless species that might otherwise vanish unnoticed.Baker was interviewed by Mongabay’s Rhett Ayers Butler in October 2025.

See All Key Ideas

California has a way of exaggerating things—mountains, deserts, and egos. But its insects? They take excess to another level. Somewhere between the redwoods and the Salton Sea live perhaps 30,000, maybe 35,000 species. Nobody really knows. That’s the problem—and the provocation—behind the California Insect Barcode Initiative, a monumental effort to document them all, one DNA sequence at a time.

Austin Baker, a postdoctoral researcher at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, is leading the charge. His brief is almost absurdly ambitious: to collect, sequence, and catalog every insect species in the state. Every fly, ant, and beetle that hums, crawls, or burrows across the Golden State.

“You could visit any vegetated area across that state and potentially collect several new (undiscovered and unnamed) insect species,” he says.

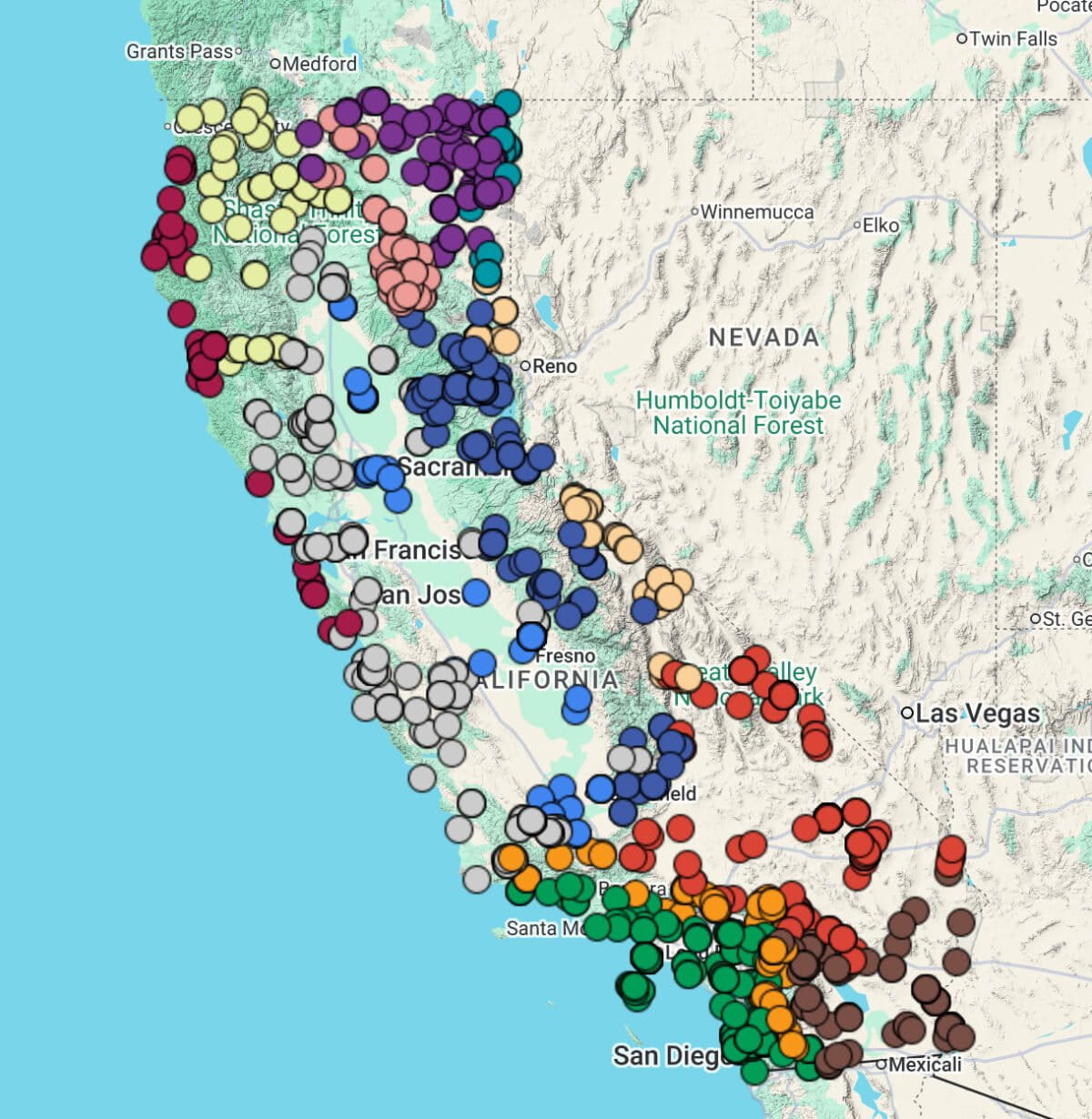

Insect collection locations across California for the barcoding initiative. Points are colored by the ecoregion where the collection occurred.

Insect collection locations across California for the barcoding initiative. Points are colored by the ecoregion where the collection occurred.

The task sounds Sisyphean. California’s habitats are diverse—fog-draped coasts, alpine forests, and blistering high deserts. Baker and his colleagues, working under the umbrella of the California All-Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (CalATBI), are sampling every ecoregion recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency. Each biome gets its turn.

“We’ve decided to try to sample every ecoregion within the state using as many collecting techniques as we can,” Baker explains.

And not just once. Many insects emerge only for a few fleeting weeks each year, so the team deploys passive traps that can sit in place for months, quietly filling with wings, legs, and data.

Their project, part of CalATBI’s larger mandate to “discover it all, protect it forever,” aims to create a genetic library of California’s biodiversity. But it’s not just a modern exercise in sequencing. Every specimen is kept, tagged, and archived.

“DNA barcoding is an excellent way to discover and delimit species, although it is not perfect,” Baker says. “Verifying accuracy requires going back to the voucher material for further examination.”

The phrase favored by the CalATBI—“Without a specimen, an observation is just a rumor”—rings true for him. A pixelated photo of a fly on iNaturalist might help with crowd-sourced identification, but it can’t replace a body in a jar.

Austin sweeping the vegetation for insects at one of the highest elevation collecting points for the project in the White Mountains. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Austin sweeping the vegetation for insects at one of the highest elevation collecting points for the project in the White Mountains. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Collecting those bodies has taken a small army. Scientists from UC Berkeley, the California Academy of Sciences, and a dozen other institutions coordinate with park rangers and volunteers to fan out across the state. Collaboration, Baker admits, hasn’t always been simple.

“Scientists have a lot of really good, but often differing, opinions about what the goals and methods should be,” he says. “Getting everyone on board with a unified approach early on was essential.”

For Baker, who once spent his days chasing parasitoid wasps that lay eggs inside ants, this is a leap in scale but not in spirit. He likes messy systems—things with too many moving parts. “Knowing about the life history and biogeography of insects was important for figuring out when, where, and how to collect them,” he says. His earlier work on crickets and katydids, heavy on genetics, gave him the sequencing chops for the current project.

California’s abundance never fails to impress him.

“It was surprising to learn that the Mojave Desert is one of the most species-rich areas that we sampled,” he says. “Some areas in the Mojave and the Southern California Mountains could host over 8,000 species per square kilometer.” You wouldn’t know it from the silence and dust, but a desert hillside may host more life than a rainforest leaf.

Insects, like these weevils, are often camouflaged to blend in with their environments. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Insects, like these weevils, are often camouflaged to blend in with their environments. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Baker bristles a little at the term “insect apocalypse,” popularized by reports of collapsing insect biomass around the world. He prefers precision to panic.

“Losses in insect diversity and abundance aren’t happening in a uniform way across the world,” he says. “This project is taking measurements of diversity and abundance across California for the first time to provide future surveys a baseline point of comparison.”

If that sounds abstract, consider what’s at stake. Insects pollinate crops, decompose waste, and feed birds and fish. They are, as Baker puts it, “the base of many food webs.” And because they react quickly to temperature shifts and habitat changes, they are also the first to signal environmental trouble.

A female Arizona mantis taking a defensive posture. Image by Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

A female Arizona mantis taking a defensive posture. Image by Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Baker’s own path began far from home, in the damp forests of Queensland, Australia.

“This class required building an insect collection, which I found very fun,” he recalls. “The area was full of gigantic, beautiful insects.”

That spark carried him through a Ph.D., and now into a statewide search for species no one has ever seen before.

It’s work that depends as much on patience as passion. Sorting thousands of tiny bodies, comparing DNA sequences that differ by fractions of a percent. But every vial, every barcode, is a story—proof that something once lived here. And perhaps, if the effort succeeds, will live on.

Austin Baker

Austin Baker

An interview with Austin Baker

Rhett Ayers Butler for Mongabay: You’ve described California as one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. What does it mean, in practice, to attempt to barcode every insect species in the state?

Austin Baker: The California Floristic Province is described as one of the world’s 25 “biodiversity hotspots”, defined by containing an exceptional concentration of endemic species facing severe habitat loss. What this means as a collector attempting to barcode every insect species is that you could visit any vegetated area across that state and potentially collect several new (undiscovered and unnamed) insect species. California has an enormous diversity of habitats (coast, mountains, deserts, and everything in between), so to sample all of the species, or at least as many as humanly possible, within the project’s timeframe, we’ve decided to try to sample every ecoregion (as defined by the Environmental Protection Agency) within the state using as many collecting techniques as we can. In addition to the spatial diversity, we also need to consider seasonal diversity, because many species of insects are only active at certain times of the year. This requires deploying many passive traps that can stay in the field for months or even years, and collecting samples from those traps on a weekly basis.

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles field technicians at Stunt Ranch Reserve (from left to right): Nathan Tang, Jesse Laine, Sylvia Reyes

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles field technicians at Stunt Ranch Reserve (from left to right): Nathan Tang, Jesse Laine, Sylvia Reyes

Mongabay: The California Insect Barcode Initiative (CIBI) is part of the larger CalATBI effort to “discover it all, protect it forever.” How does your work fit into that vision?

Austin Baker: When it comes to invertebrates (insects, arachnids, nematodes, etc.), there are a huge number of species that have yet to be discovered and formally named in a scientific way. Because of this, we have no way of knowing how many species there are, where those species can be found, if the distributions or populations of those species are expanding or declining, or if invasive species are impacting the native ones. We desperately need some baseline knowledge of the biodiversity of California if we want to understand things like extinction rates and conservation priorities for the future.

Mongabay: CalATBI emphasizes both DNA sequencing and voucher-based specimens. Why is it so important to maintain physical collections in an age of genomics?

Austin Baker: DNA barcoding is an excellent way to discover and delimit species, although it is not perfect. Species of some groups can be recognized with over 98% accuracy with this method, but other groups may have a lower percentage, and verifying accuracy requires going back to the voucher material for further examination. If new species are discovered from their DNA sequences, voucher specimens are required for further study, including describing those species. Maintaining physical collections is also essential for any older collections that cannot be sequenced. In order to associate DNA sequences to species names for those that are already described, it requires comparing the sequenced voucher specimens to the described type specimens.

Austin is digging through cow dung for beetles. Collecting is not always pleasant. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Austin is digging through cow dung for beetles. Collecting is not always pleasant. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Mongabay: The project relies heavily on partnerships across institutions and parks statewide. What have you learned about collaboration—scientifically and logistically—through this process?

Austin Baker: Large collaborations require a coordinated effort to maximize efficiency and to build a dataset that has the highest utility possible. I learned that clear cut goals and methods are necessary for the larger effort to be successful. Scientists have a lot of really good, but often differing, opinions about what the goals and methods should be, so getting everyone on board with a unified approach early on was essential.

Mongabay: Insects are often underappreciated despite being the foundation of most ecosystems. What do you wish more people understood about their importance to California’s environment?

Austin Baker: Insects provide many important ecosystem services: pollination, decomposition, pest control, and providing the base of many food webs for birds, fish, reptiles, etc. What many people don’t realize is that insects are also an excellent model group for monitoring large-scale changes in communities and ecosystems. There are many species that are highly endemic, sensitive to changing environments, and reliant on temperature for development, which means that changes in the local environment are going to be seen first and most dramatically in the insects. Additionally, the number of species per unit area is greater than any other group, allowing for more precise measurements of biodiversity for comparison across sites and over time.

Mongabay: You’ve spoken about the “insect apocalypse”—declines in both abundance and diversity. How can barcoding and large-scale inventories help us understand or respond to those losses?

Austin Baker: Losses in insect diversity and abundance aren’t happening in a uniform way across the world, some areas are experiencing greater declines than others, but these patterns are not well understood due to a lack of long-term monitoring. This project is taking measurements of diversity and abundance across California for the first time to provide future surveys a baseline point of comparison. This will help us respond to losses in the long-term by providing critical data needed to assess changes in species distributions, environmental factors that may be correlated to population declines, and areas that may be the most critical for conservation efforts.

(left) A hairstreak butterfly about the size of a fingernail; (center) Timema are walking sticks endemic to California; (right) The ceanothus silkmoth is one of the largest moth species in California. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

(left) A hairstreak butterfly about the size of a fingernail; (center) Timema are walking sticks endemic to California; (right) The ceanothus silkmoth is one of the largest moth species in California. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Mongabay: Are there particular species or habitats in California that have surprised you—places where biodiversity turned out to be far richer or stranger than expected?

Austin Baker: California is full of insects everywhere you look, but it was surprising to learn that the Mojave Desert is one of the most species-rich areas that we sampled. Our estimates suggest that some areas in the Mojave and the Southern California Mountains could host over 8,000 species per square kilometer.

Austin and his technician, Nathan Tang, searching the sand dunes for insects at Death Valley National Park. Image credit Jesse Laine

Austin and his technician, Nathan Tang, searching the sand dunes for insects at Death Valley National Park. Image credit Jesse Laine

Mongabay: Much of your background focuses on parasitoid wasps and the evolution of hearing in crickets and katydids. How do these earlier studies inform your approach to large-scale biodiversity work today?

Austin Baker: My Ph.D. research on parasitoid wasps involved a lot of field work across the United States and a few other countries as well, including Trinidad, Costa Rica, and New Zealand. This field experience was very important for learning many of the techniques that we use in this study. Having a background in taxonomy was also very helpful for understanding the groups we are collecting for the present study. Knowing about the life history and biogeography of insects was important for figuring out when, where, and how to collect them. My postdoctoral research on crickets and katydids was very genetics-heavy, which gave me a very good background on sequencing and interpreting genetic data, which is a major part of the current project.

Mongabay: The phrase “Without a specimen, an observation is just a rumor” captures the ethos behind CalATBI. How does that sentiment resonate with your own philosophy as a researcher?

Austin Baker: I am a huge advocate for natural history collections. A physical specimen is far more valuable than just an observation record, however, with modern digital imaging technology constantly improving, platforms like iNaturalist have a lot of value for the scientific community too. That said, certain groups of insects will never be identifiable from images alone, like small flies and parasitic wasps, which even experts can misidentify without examining several lines of evidence, including DNA. Taxonomy can change as new data is acquired, for example, what was once thought to be a single species could end up being two or more different species twenty years later, so preserving specimens allows us to revisit and update identifications.

Austin hand collecting beetles at night in the desert. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Austin hand collecting beetles at night in the desert. Image credit Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Mongabay: What was your own path into entomology—was there an early experience or mentor that first sparked your fascination with insects?

Austin Baker: I took my first entomology class while studying abroad at James Cook University in the tropical rainforests of Queensland, Australia. This class required building an insect collection, which I found very fun, especially since the area was full of gigantic, beautiful insects. When I returned to my home institution, Oregon State University, I joined Dr. David Maddison’s lab as an undergraduate research assistant. David taught me a lot about beetles, systematics, and working in a laboratory, and he piqued my interest enough that I decided to pursue insect systematics for my Ph.D. research.

(left) Darkling beetles excrete foul-smelling chemicals from their abdomens when disturbed; (center) A skimmer dragonfly waiting at the edge of a pond; (right) Austin sweeping flowers to look for pollinating insects. Images by Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

(left) Darkling beetles excrete foul-smelling chemicals from their abdomens when disturbed; (center) A skimmer dragonfly waiting at the edge of a pond; (right) Austin sweeping flowers to look for pollinating insects. Images by Nathan Tang and Jesse Laine

Mongabay: Many of the next generation of scientists come to biodiversity through community science or photography rather than formal study. What advice would you give to people who want to get involved in insect research or conservation?

Austin Baker: Joining groups like Adventure Scientists is a great way to get involved in real research that has a biodiversity and conservation focus. Adventure Scientists helped us connect with community members that collected insect specimens for our barcoding project. iNaturalist is another great platform to get involved in research projects. We have collaborators who image specimens and then collect them to provide the community with observation records and provide the barcoding project with specimens to sequence.