When California became a state on Sept. 9, 1850, it was due in large part to the Gold Rush. Thousands of prospectors flowing into the once sparsely populated territory made forming an organized government an urgent necessity. It was a fitting start. California’s trajectory since its founding has been guided by similar trends of migration, innovation and ambition.

At a recent Dornsife Dialogues event hosted by the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, scholars from the College and The Huntington dug into key points across 175 years of California’s history, ranging from ancient wolves to the origins of California’s powerhouse tech industries.

Find a transcript of this audio here under the transcript tab.

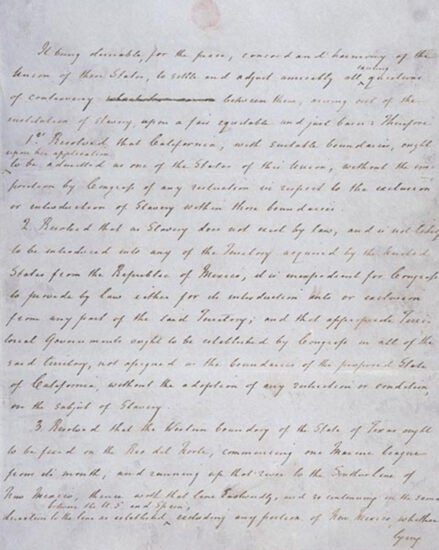

This handwritten resolution introduced by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay eventually formed the basis of the 1850 Compromise. (Image Source: National Archives.)

This handwritten resolution introduced by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay eventually formed the basis of the 1850 Compromise. (Image Source: National Archives.)

The Compromise of 1850

Many may be unaware of California’s role in the eventual abolition of slavery in the United States, says Alice Baumgartner, associate professor of history. “We think of California as very separate from the sectional controversy between North and South, but it really is central to understanding that story.”

After the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, newly acquired territories began to formally join the U.S. as states. Existing slave states and free states clashed on whether legal slavery should be extended to these areas. California had petitioned to join the Union as a free state, which would greatly upset the balance of power between the two sides.

To solve the debate, Congress passed the Compromise of 1850. Among other laws, it left the legality of slavery up to the residents of each state. Although the compromise failed to prevent the Civil War, it likely forestalled it for a decade, says Baumgartner.

California’s Chinatowns

German-American photographer Arnold Genthe took many photos of San Francisco’s Chinatown at the turn of the 20th century. (Image Source: Library of Congress.)

German-American photographer Arnold Genthe took many photos of San Francisco’s Chinatown at the turn of the 20th century. (Image Source: Library of Congress.)

In addition to gold-hunting prospectors, Chinese immigrants also arrived by the thousands to seek theirfortune and a new home. By 1870, they made up some 20% of the adult male working population, says Nayan Shah, professor of history and American studies and ethnicity.

This immigration was followed by legal limits. The Page Act of 1875, which banned the arrival of conscripted laborers and effectively ended immigration of Chinese women, was sponsored by Californian Senator Horace Page. It became the United States’ first federal immigration law.

Despite the obstacles, Chinese arrivals continued to establish themselves. Chinatowns can still be found across California, from large cities to small hamlets. They were a source of fascination for many whites and European immigrants, says Shah, including Arnold Genthe, who captured images of San Francisco’s Chinatown at the start of the 20th century.

Silicon Valley boots up

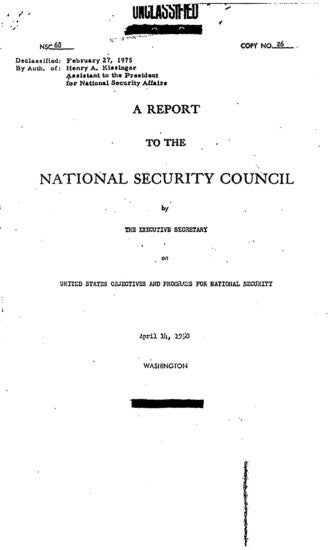

This a top-secret report was completed by the U.S. Department of State’s Policy Planning Staff. (Image Source: National Security Council.)

This a top-secret report was completed by the U.S. Department of State’s Policy Planning Staff. (Image Source: National Security Council.)

California’s technology prowess owes its start in part to National Security Council Paper NSC-68, says Peter Westwick, professor of the practice of thematic option and history.

This 1950 report concluded that a Cold War with the Soviet Union would be long-term and recommended tripling the defense budget. It was a boon for California. Hundreds of billions of federal dollars built up robust defense facilities in the state and provided well-paying jobs to many. This kicked off aerospace, electronics and computing industries in Silicon Valley, laying the groundwork for today’s celebrated technology hub.

With so many employed for the government on defense projects, secrecy became routine. Workers underwent security screenings and often couldn’t share what they did with family. It may have played a role in later, “paranoid” culture vibes of the 1970s, captured well in Thomas Pynchon’s novel Inherent Vice.

“There’s a vast, subterranean aspect of Californian society in this period, the social and cultural implications which, I think, is fundamental for California,” says Westwick.

Cutting-edge environmental protection

California contains 124 marine protected areas. (Image Source: California Ocean Protection Council.)

California contains 124 marine protected areas. (Image Source: California Ocean Protection Council.)

Innovation also extends toward California’s policy choices. In 2000, the state passed a law mandating the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). These are designed to protect fragile ecosystems, rebuild dwindling marine species, and improve recreational opportunities for Californians.

“Carrying out this type of work in 2000 was way ahead of the curve and created an example for the rest of the world,” explains Jill Sohm, professor (teaching) of environmental studies.

One of these MPAs can be found near USC. The Blue Cavern MPA off the coast of Catalina Island sits adjacent to the USC Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability’s Wrigley Marine Science Center. There, species like the Giant Sea Bass are protected from fishing, allowing them safe space to spawn and repopulate California’s waters.

Dire Wolves and Grizzly Bears, oh my!

Long before California became a state, dire wolves roamed the land, says Dan Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator for the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington. Many of these wolves met their end in what is now the La Brea Tar Pits, where gluey asphalt trapped thousands of animals. Paradoxically, their sticky demise has given them a new chance at life.

Dire wolves and a saber-toothed cat fight over a carcass in the La Brea Tar Pits, site of many an ancient creature’s end. (Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Dire wolves and a saber-toothed cat fight over a carcass in the La Brea Tar Pits, site of many an ancient creature’s end. (Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Colossal Biosciences recently made the cover of Time magazine with their claim that they’d resurrected the dire wolf. Using DNA extracted from a jawbone retrieved from the pit, scientists genetically modified grey wolf embryos and produced pups.

How truly dire wolf the cubs are remains contested, but its renewed debate about the ethics of reviving extinct species, says Lewis.

That’s a conversation of deep importance for California today. Its native species of grizzly bear (which adorns the state flag) was hunted to extinction by the 1920s. Relatives from Montana or Idaho could provide the stock for a reintroduction.

Are hikers ready to encounter a grizzly once again in the Sierra mountains? A recent poll showed that two-thirds of Californians support their theoretical return, perhaps a sign that the Californian appetite for adventure ever endures.