Why this matters

As the Trump administration detains a record number of immigrants across the U.S., judges in San Diego and other parts of the country are finding some were unlawfully detained.

Federal judges in San Diego ruled on more than two dozen occasions this year that immigration officials detained immigrants unlawfully or likely violated their rights in the process, according to a review of court records by inewsource.

The decisions come from legal petitions filed by immigrants inside detention centers in Southern California, many of whom argued with the help of attorneys that they were swiftly arrested by immigration authorities without proper procedure and wrongfully subjected to mandatory detention.

As President Donald Trump’s administration reverses protections for immigrants en masse and overturns decades of standard practice, federal judges are increasingly rejecting the government’s legal basis for individual detentions.

In a statement to inewsource, the Department of Justice defended its actions as appropriate interpretations of the law and suggested that immigration proceedings were before now improperly adjudicated. A spokesperson for the DOJ said the agency would, with the president, continue to enforce the law and protect the American public.

Among those who have been detained and later ordered released by judges are asylum-seekers who entered the country through ports of entry, have no criminal record and were detained after attending their immigration court hearings: a woman who fled Venezuela after suffering a violent rape by police; a U.S. ally left behind in Afghanistan after the Taliban took over Kabul; a teenager who defied an oppressive government regime in Nicaragua and feared grave retaliation, according to federal court records filed by their attorneys.

They also include immigrants with criminal records who have lived in the country for decades. In two cases, judges found “troubling” allegations against the Department of Homeland Security’s actions and, in one of those, that the agency made “blatant procedural errors” and “gravely violated” the petitioner’s rights.

Habeas corpus, a constitutional right through which immigrants are now challenging their detentions, is becoming an increasingly common strategy amid concerns of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions inside detention centers.

So far this year, 16 people have died while in immigration detention across the U.S. The Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego and Imperial Regional Detention Center in El Centro have a combined average daily population of about 2,000 people, according to the most recent data from ICE.

Kirsten Zittlau, who has practiced immigration law in San Diego for seven years, filed her first habeas case in August. Since then, she’s filed five more.

“Habeas is becoming really necessary if you wanna get anybody out of custody, and that can sometimes be the most important factor in the case,” Zittlau said. Outside of custody, they may be better equipped to gather evidence for their case or start working to pay an attorney, she said.

The Venezuelan woman, whom Zittlau represents, entered the U.S. more than two years ago, when she was granted parole, a temporary protection from deportation.

When Trump took office again, his administration sent a mass email to parolees notifying them that their parole would be revoked within seven days. Zittlau’s client never received the email, but immigration authorities still arrested her outside her immigration hearing in August.

“You’re detaining people who did everything exactly right,” Zittlau said of the government.

As petitions rise, judges find violations of law

So far this year, judges in San Diego have granted 26 habeas petitions in full or in part. In some of the cases, the judges have ordered the immigrant’s immediate release and others required that they receive a bond hearing. Only four cases have been denied outright and 22 have been dismissed, according to inewsource’s analysis.

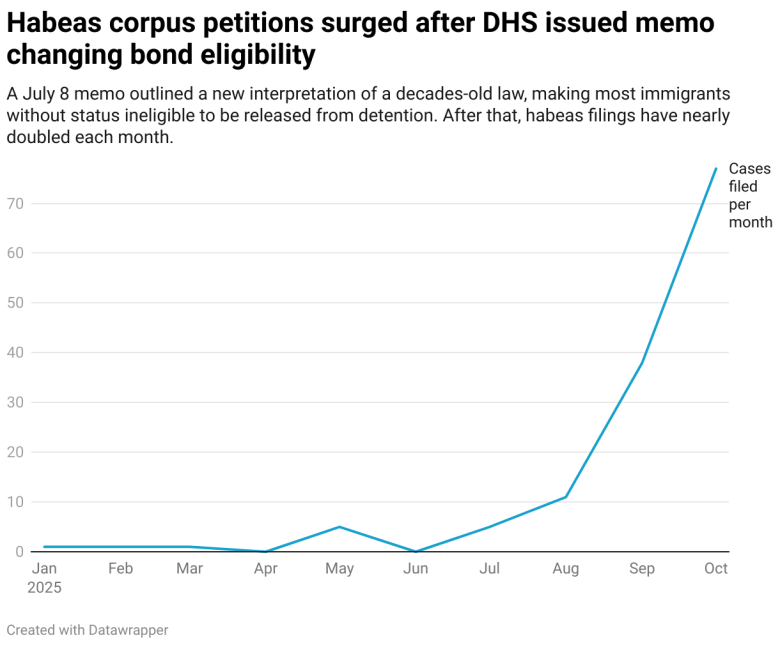

In the Southern District of California, the federal court district that includes San Diego and Imperial counties, the number of filings overall have roughly doubled each month since July.

That month, Todd Lyons, ICE’s acting director, issued a memo explaining that the agency had decided to reinterpret longstanding immigration law. The result of the new interpretation: Most immigrants who crossed the border unlawfully — even if they’ve lived in the U.S for years and have no criminal record — were now ineligible for bond.

Months later, a ruling from the Board of Immigration Appeals, which falls under the Department of Justice and whose members are appointed by the U.S. Attorney General, upheld that position.

Before, migrants who had no significant criminal record and were not deemed a flight risk could be eligible for bond and be released to join their family while their immigration cases proceeded. Now most of those picked up and detained by immigration officials must wait in detention.

The change is one of several reasons why immigration detention has reached record levels this year and why judges are ruling against the government in habeas petitions, according to Suchita Mathur, senior litigation attorney with the American Immigration Council.

“The government is trying to apply this statute to people who have been living in this country in some cases for many, many years. The federal courts are pushing back and saying that is not the correct reading of the statute,” Mathur said.

The bond ruling isn’t the only policy change that attorneys are challenging in the petitions and winning. Earlier this year, the Trump administration revoked parole statuses for immigrants who entered the country through the Biden-era program called CBP One.

More than 900,000 immigrants entered the U.S under the Biden administration after making an appointment with the government officials through the CBP One app. The Trump administration began sending emails to immigrants in April, notifying them that their parole was being revoked.

Attorneys argued in habeas filings that the parole revocation was unlawful, in part because it provided no specific and individualized reason, violating due process rights and federal procedure law. In other cases, attorneys said that the government revoked release orders for immigrants without giving proper notice or an opportunity to respond, as required by law.

In one such case, ICE officials did not provide a warrant for a man’s arrest until weeks after he was taken into custody. The warrant also contained a date discrepancy — it was issued on Sept. 1 but the ICE field office director’s signature was dated July 14 — which the government “was unable to address” in a court hearing, according to court filings.

“After-the-fact determinations in an attempt to justify a noncitizen’s re-detention cannot cure the Government’s blatant procedural errors. Especially when notice is provided in an egregious and untimely manner such as this,” the judge in that case wrote in his order.

In another case, the government kept a Mexican man detained for seven months while officials said they were trying to deport him to a country other than Mexico. The Supreme Court has ruled that immigrants with final removal orders cannot be held in custody longer than six months if the government cannot show that the deportation is likely to happen.

ICE kept the man in custody after three countries refused to receive him and as officials told him that they had not worked on his case for two months, according to allegations in the court filings.

Habeas petitions can require intensive work for attorneys and while they can end someone’s detention, it’s not the end of their immigration proceedings to determine whether they can stay in the country.

Still, attorneys are leaning into the strategy, and according to some groups attempting to track these cases, the number of petitions are on the rise in places across the country and are proving successful.

“It’s a strain on attorneys and the courts and the government, but most of all, it hurts the folks who are in detention for absolutely no reason,” Mathur said.