A new congressional district map approved by California voters Tuesday in direct response to redistricting in Texas gives Democrats a chance they wouldn’t have had before to take control of the House in 2026, a Northeastern University expert says.

“It’s a very tightly divided Congress,” says Mark Henderson, professor of public policy on Northeastern’s Oakland campus. “In the absence of this measure passing in California, but with Texas adding the seats that they are engineering, it would be entirely impossible for the Democrats to take control of the lower House. With this passing, it’s possible that the Democrats could do it. So it’s gone from impossible to possible.”

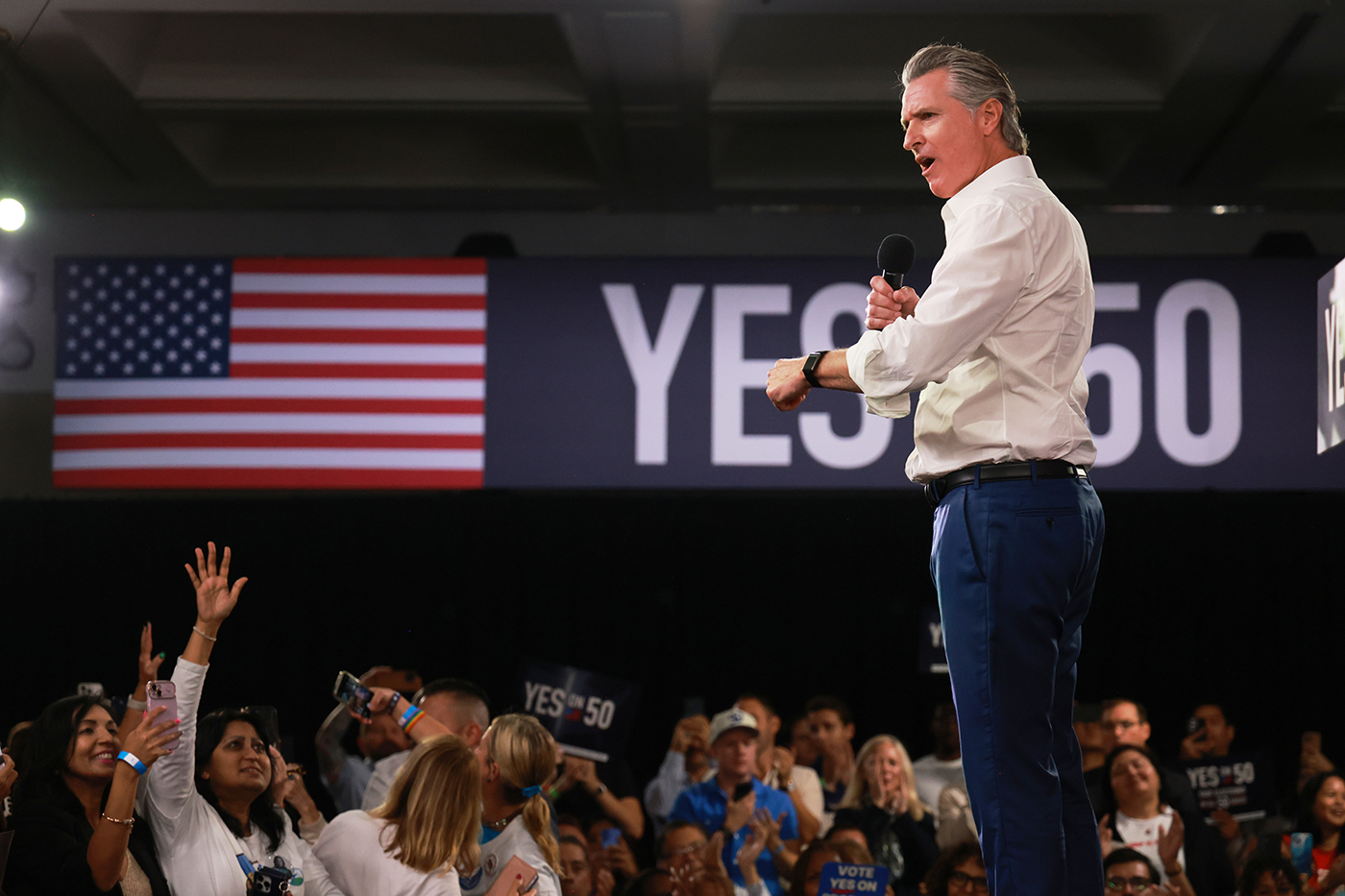

Proposition 50 passed with nearly 64% of the vote and could send up to five additional Democratic representatives to Congress. In a major win for Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, the Associated Press called the results the moment polls closed based on the number of mail-in ballots. A coalition of California Republicans filed a lawsuit Wednesday to block the state’s new map.

The measure asked voters to approve or reject “temporary changes to congressional district maps in response to Texas’ partisan redistricting.” The new map was designed to boost the number of seats for Democrats in the 2026 midterm elections.

Republicans have a six-vote majority over Democrats in the House of Representatives, 219 – 213.

Mid-cycle redistricting efforts in California, Texas and a handful of other states are “unprecedented,” Henderson says. While state procedures for drawing district maps vary, all states use census data collected every 10 years. The next census is scheduled for 2030.

The wave of redistricting efforts was set into motion when the Texas legislature approved a new congressional map in September designed to flip five Democratic seats to favor Republicans, setting off talk of redistricting in a number of other states. Only California took the question to voters this month, but other states are pursuing the process legislatively.

When one state changes its district maps, another state with a majority of voters from the opposite party is likely to follow suit, says Nick Beauchamp, associate professor of political science on Northeastern’s Boston campus.

“States do various things to try to maximize the state level goals,” he says. “So if the state is 52% Republican, they’re going to want to get 100% of their seats to be Republican. If it’s 52% Democrat, they’ll do the opposite.”

In California, an independent Citizens Redistricting Commission draws new maps when new census data becomes available. The new map approved by the passage of Proposition 50 will only apply to elections held in 2026, 2028 and 2030. The commission will redraw that map based on 2030 census data.

In October, the North Carolina state legislature voted to move six coastal counties and precincts in another county into a district currently held by a Democrat, making it more favorable to Republicans. In September, Republican Gov. Mike Kehoe of Missouri signed a revised congressional map into law. Lawmakers in Indiana plan to meet in early December to consider new congressional maps, and the Florida state legislature formed a select committee in August to redraw maps.

“We’ve never had mid-decade redistricting,” Henderson says. “Basically, states set their districts once a decade and that’s the structure of power for the next 10 years. And then we count the people again and reallocate seats.”

But as the two major political parties in the U.S. have become more polarized, Henderson says, congressional district maps have evolved to become more focused on national party platforms than local issues.

“There was a long period of time where we had moderate Republicans and we had more conservative rural Democrats, and that’s basically been filtering out,” he says. “I hate to use the phrase ‘battle lines,’ but the lines between the parties have sharpened for the most part.”

It is easier than ever now to manipulate the outcomes of district lines, says Beauchamp, with data analytics tools that make processing census data faster and more efficient.

“Maybe that was the Pandora’s box,” he says. “This was always the vulnerability in the system and then the technology finally caught up to allow people to really maximize that vulnerability.”