Special education teacher Danielle White, 31, lost her life savings to phone scammers in October. Credit: Danielle White

Special education teacher Danielle White, 31, lost her life savings to phone scammers in October. Credit: Danielle White

Around 2 p.m. on Oct 20, Danielle White was at work for her job as a special education teacher at Berkeley’s John Muir Elementary School when she got a call from four Oakland police officers. They said the call was being recorded for her safety and theirs and gave her their badge numbers.

“They said that I had missed a court appearance and that I was supposed to be on this jury,” White told Berkeleyside in a phone interview.

Twenty-seven hours later, and nearly $70,000 poorer, White realized the truth: The cops weren’t cops, there was never any jury assignment and the arrest with which they had threatened her never would have come to be.

But for those 27 hours the scammers, who ripped off the 31-year-old teacher of her life savings, kept her isolated from anyone else in order to control her reality — using fear, sound effects and fake identities, she said, to drown out any reservation that bubbled up in her mind.

“Obviously now, kind of listening and hearing this story, it sounds crazy,” White said.

Not at all, say Berkeley police, who are now investigating.

Over 100 similar fraud cases in Berkeley last year

“Sadly, this is not the first time I have heard a story like this,” Berkeley police spokesperson Officer Byron White (no relation to Danielle White) wrote in an email.

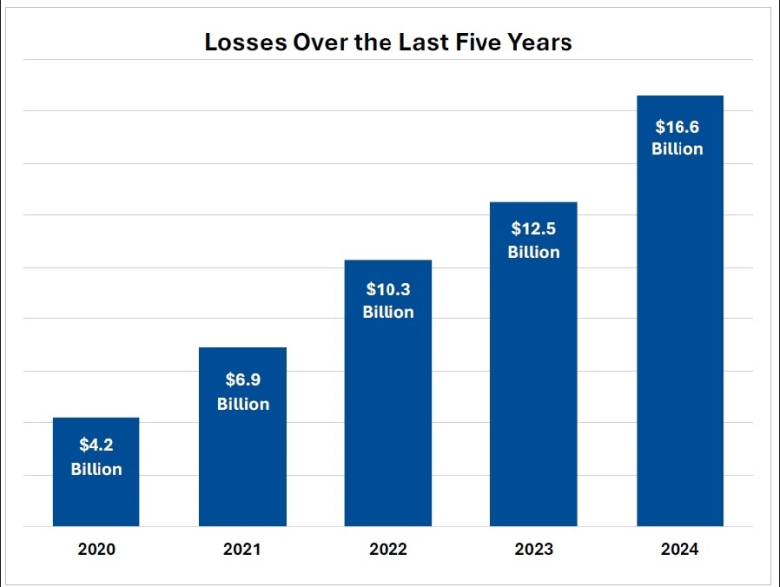

The FBI lists this exact strategy as one of the more common types of fraud. Digital scammers, using phones and the internet, took an estimated $16.6 billion last year across the country, according to the FBI.

Digital scammers have ripped off Americans of tens of billions of dollars since 2020, according to the FBI. Credit: FBI

Digital scammers have ripped off Americans of tens of billions of dollars since 2020, according to the FBI. Credit: FBI

State agencies have made some progress at penalizing the cryptocurrency ATM operators whose machines make these scams possible — White was directed to deposit cash into ATMs around Oakland — but catching the scammers who are actually perpetrating the fraud is more difficult.

The scammers “are often out of the area — often using Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) phone lines that can ‘spoof’ their true locations,” Officer White said.

This type of fraud, officially “false personation and cheats” under California law, is a regular crime in Berkeley, with 110 reports over the last year, according to police data. Of those 110, however, it is unclear how many may have involved a scheme as convoluted as the one that targeted Danielle White.

Pay now, or go to jail for three days

The scammers struck Danielle White at a particularly vulnerable time. Just two months earlier she had been in a crash that totaled her car. Earlier in the year she had moved out of her mother’s home in Richmond into a new home in Berkeley, where she paid higher rent to live in the city where she grew up and now works. And while special ed teachers rarely have quiet months, October becomes especially frenetic between report cards, parent-teacher conferences and education planning for her students all happening at once.

So, she said, she was not at her “best mental state” when the scammers, posing as Oakland cops, said they had her signature agreeing to serve on a jury, tied to an old Oakland address where she had once lived.

The “officers” said there were a number of citations in her name. She could come down to police headquarters to clear the matter up, but not before paying thousands of dollars to “freeze” the citations. If she came in before paying the fees, she would be arrested, and would be held three days before so much as seeing a judge.

To a person facing lockup, a chance to pay the way out seems just good enough to be true. For these scammers it was the worm covering their hook. They sent Danielle White official-looking documents, convincing her she was under a gag order. She was not to speak to anyone other than the “officers,” and under no circumstances could she hang up the phone, even overnight.

They convinced her they could detect data spikes when she used other devices.

California hits back at crypto ATMs popular with scammers

The hook sunk, the scammers pulled harder. The first day they persuaded her to withdraw just a few thousand dollars. But the next day they piled on new imaginary fees, including “overnight charges” to pay the very bogus officers they claimed to be. She would withdraw tens of thousands of dollars at a time from her bank, then feed it, $1,000 increment by $1,000 increment, into crypto ATMs, delivering it to the scammers through QR codes.

Two of the ATMs, both belonging to Chicago-based CoinFlip, were in smoke shops, one on San Pablo Avenue at the Emeryville Border, the other on Webster Street downtown. The third, belonging to Atlanta-based Bitcoin Depot, was in a gas station in East Oakland.

The reason the ATMs only accept $1,000 at a time is because the state has forbidden them from distributing or accepting more than that to or from the same person in a given day.

Danielle White made several trips to a downtown Oakland smoke shop to deposit much of her life savings, $1,000 at a time, into this crypto ATM. Credit: Alex N. Gecan/Berkeleyside

Danielle White made several trips to a downtown Oakland smoke shop to deposit much of her life savings, $1,000 at a time, into this crypto ATM. Credit: Alex N. Gecan/Berkeleyside

Just this summer the state Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) served the first enforcement action under the 2023 law that established the transaction limit. They fined Seattle-based Coinme Inc., another crypto ATM operator, $300,000 for violating the limit and other offenses. Of that, $51,700 went to Californians who had fallen prey to similar scams as the one that cleaned out Danielle White.

White said she made just a single, $1,000 deposit at the East Oakland Bitcoin Depot ATM on Oct 20, within the transaction cap. The balance went into the CoinFlip ATMs, both of which she visited several times Oct. 20 and 21. One of those displayed a placard indicating the transaction limit, but with no clarification that the onus was on the operator.

In an email, a CoinFlip spokesperson said the company was “saddened to hear about this experience, and we never want to profit from honest people being scammed.” The spokesperson said the company refunds transaction fees — though not transaction amounts — to fraud victims, “and our team is working with the customer on that process.” Those fees range from roughly 5% to roughly 22% of transaction amounts.

Bitcoin Depot also emailed a statement to Berkeleyside, writing that “we will take appropriate steps to review and, if warranted, refund the transaction based on our findings.” It emphasized that White’s transaction with Bitcoin Depot was within California’s cap.

Phone scammers used police jargon and radio noises

The scammers, all men to White’s ears, told her she would get all her cash back once she’d cleared up the whole jury service mixup. They spoke in police jargon, and had what sounded like official radio transmissions playing in the background. Four different men took turns speaking to White through the ordeal, sometimes calling her “honey,” sometimes “ma’am.” One man had a slight Southern accent. The rest, she said, sounded local.

One man did most of the talking, and did so in a “calming and comforting” way, she said.

At first overwhelmed, then confused, stifling her own fears, “I just kind of followed what they were saying, trying to convince myself that everything would be OK,” she said. “I wanted it to be real, in a sense, because I wanted to get my money back. … When I found out it was a scam, it was completely devastating and heartbreaking.”

With her savings drained, the scammers were still demanding more money, but they finally let White make a phone call to someone else — then after she had, accused her of violating the gag order. That was one inconsistency too many. She contacted a friend who convinced her of what was really going on and, after more than a day, she finally hung up on the fraud team.

The friend and White’s mother came to meet her, and she went straight to Berkeley police. She has also filed complaints with the state DFPI and the FBI, but has not yet had any update.

White’s friends and family have started a GoFundMe account to try to help her recoup some of her savings which, she had hoped, she could someday use toward buying a house and starting a family. As of Thursday it was a little over halfway to its $7,000 goal, just one tenth of what the scammers took from White.

“You live your life trying to be a good person and believe in people and their intentions, and want to believe that other people are good and honest and unfortunately it’s not always the case,” White said.

Challenging as this has been, White counts herself blessed to have loved ones that have her back when she’s down — friends, like those in her Berkeley hula community; family, like her cousin Alaina Brookmyer, who set up the GoFundMe; and colleagues like her principal, Paco Furlan, who first brought the scam to Berkeleyside’s attention and praised White’s dedication to the Bay Area’s children with special needs.

“That’s not always the case with other people that this happens to,” White said.

Here are some tips from the FBI and Berkeley police to keep yourself safe:

Scammers will change aliases and tactics; however, the scheme generally remains the same.

Never share sensitive information with people you have met only online or over the phone.

Scam victims can file complaints with BPD or with the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), the division that investigates scams. (Note: Law enforcement scammers are so brazen they have begun posing as IC3 agents.)

The IC3 will not ask for payment to recover lost funds, nor will they refer a victim to a company requesting payment for recovering funds.

Do not send money, gift cards, cryptocurrency, or other assets to people you do not know or have met only online or over the phone.

The Berkeley Police Department will never ask you for payment over the telephone.

Any payment to the City of Berkeley would be through traditional payment means (no bitcoin, no pre-pay cards, etc).

If you are scammed, Berkeley police recommend you keep as much documentation handy as possible, including:

Names of the scammer and/or company

Dates of contact

Methods of communication

Phone numbers, email addresses, mailing addresses, and websites used by the perpetrator

Methods of payment

Where you sent funds, including wire transfers and prepaid cards (provide financial institution names, account names, and account numbers)

Descriptions of your interactions with the scammer and the instructions you were given

Whenever possible, you should keep original documentation, emails, faxes, and logs of communications.

“*” indicates required fields