A half-dozen businesses along College Avenue in the Elmwood District displayed posters opposing a plan to change zoning rules to allow mid-rise apartment buildings in the area. Credit: Nico Savidge/Berkeleyside

A half-dozen businesses along College Avenue in the Elmwood District displayed posters opposing a plan to change zoning rules to allow mid-rise apartment buildings in the area. Credit: Nico Savidge/Berkeleyside

The City Council signaled its support Thursday night for a plan to raise height limits along portions of College, Solano and North Shattuck avenues, despite mounting opposition from many residents and merchants who charge the proposal threatens the future of three popular shopping districts.

Five council members said they want to go beyond the zoning proposals presented by city planning staff and set a seven-story height cap along the commercial corridors in North Berkeley and the Elmwood District. Those areas have only seen a handful of housing projects proposed in recent years, none of which have broken ground, despite a building boom elsewhere.

“Our community is in dire need of more housing, and it is unfair to expect that certain neighborhoods — specifically districts 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 — should shoulder the entire responsibility of creating new housing,” said Councilmember Cecilia Lunaparra, referring to West Berkeley, South Berkeley, downtown and the Southside neighborhood, which she represents. “The wealthiest neighborhoods are not exempt.”

Opponents of the plan who packed Thursday night’s council meeting, meanwhile, say the proposal would allow for development too large for the low-slung blocks that are home to cherished businesses such as the Cheese Board and the Elmwood movie theater. They argue the rezoning could spark a wave of new development that pushes out small businesses to make way for housing.

“The proposed plan would disfigure our historic neighborhood corridors, displace independent merchants and forever alter the character of Berkeley,” said Claudia Hunka, owner of the Elmwood District pet supply store Your Basic Bird.

Thursday’s meeting marked the first time the council has weighed in on the rezoning proposal, which has become the latest front in a shifting housing debate that has seen Berkeley go from practically banning apartments for decades to encouraging greater density downtown, in the Southside and throughout most of its residential neighborhoods. Council members separately expressed support Thursday night for another proposal to raise height limits on San Pablo Avenue that has attracted less attention.

The council did not cast a vote on the rezoning plan Thursday night. Instead, the feedback from members will inform a round of changes to the proposal by city planning staff, who are expected to bring the plan back to the council for a final vote next summer after taking more input from the public.

Changes could bring hundreds of homes to sought-after areas

The City Council pledged in 2023 to rezone the portions of Solano, North Shattuck and College avenues as part of Berkeley’s Housing Element, an eight-year plan for meeting aggressive state development mandates. Regulators in Sacramento took particular interest in the rezoning, and pushed Berkeley to make firmer commitments to bring more homes to those streets before signing off on the Housing Element.

The effort was driven by complaints that North Berkeley and the Elmwood District weren’t taking on their fair share of new homes. Real estate developers in the Elmwood pioneered the practice of single-family zoning more than a century ago, dividing the city by wealth and race, while deed restrictions and federal loan policies worked to keep those neighborhoods off-limits to people of color for generations after that. The areas are some of the most sought-after in Berkeley today, with high housing prices to match.

The new height caps would apply on Shattuck Avenue between Virginia and Rose streets, College Avenue between Russell and Webster streets, and the parts of Solano between Neilson Street and The Alameda that are within Berkeley.

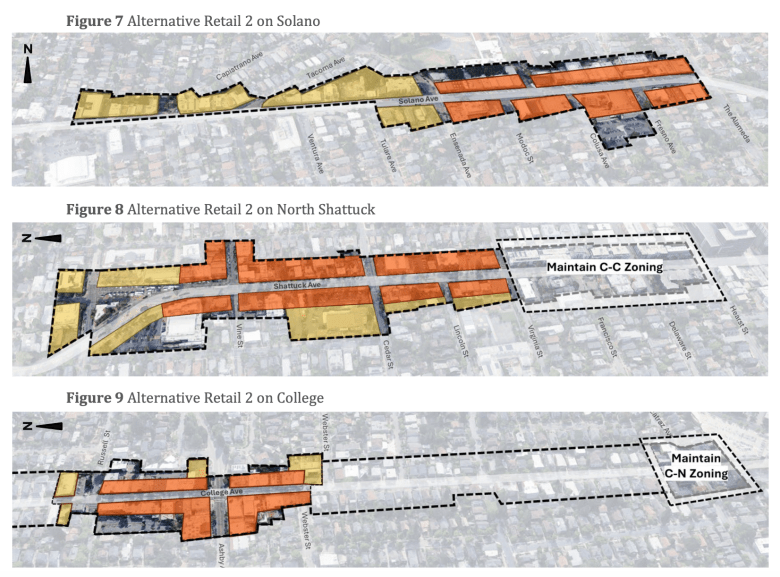

The highlighted areas of these maps are the blocks of Solano, Shattuck and College avenues that would be affected by the zoning changes. Properties marked in orange would be required to have retail space on their ground floor, while those shown in yellow could put housing there. Credit: City of Berkeley

The highlighted areas of these maps are the blocks of Solano, Shattuck and College avenues that would be affected by the zoning changes. Properties marked in orange would be required to have retail space on their ground floor, while those shown in yellow could put housing there. Credit: City of Berkeley

Those blocks have the lowest height limits of any major street in the city — buildings on Solano and College are capped at two stories, while North Shattuck tops out at three.

Draft proposals from city planning staff would raise the limits to as many as four stories on College, five on Solano and six on Shattuck. Developers could build higher by taking advantage of California’s density bonus program, which allows for taller projects in exchange for including a share of affordable apartments.

Opponents of the plan argue that opening the door to mid-rise apartment complexes along those blocks could lead to the kind of business closures that happened at the top of Center Street in downtown Berkeley, where a popular strip of restaurants was cleared out for a housing development that has since stalled.

Hunka’s shop window displays a large photo of that boarded-up block with the message, “Don’t let council do this here!” Another poster in the window shows an image, apparently generated by artificial intelligence, depicting an eight-story apartment block above a foreboding gray street with a sign that reads “Welcome to Elmwood.”

Even if they aren’t directly displaced by development, critics said, having large construction projects in the busy and congested neighborhood will dampen business for the remaining merchants, many of whom have already been battered by the pandemic and competition from online retail giants such as Amazon.

“The noise and disruption is going to scare the customers away, and the rest of the businesses are going to suffer,” said attorney and Elmwood resident Donald Simon. “That is how you kill shopping districts.”

The Elmwood has seemed to be the epicenter of resistance to the rezoning, even though planners estimate that the just over two-block portion of College Avenue is likely to see far less development than the other two streets. Developers might build as many as 130 homes in the next decade or longer along College Avenue, consultant Chris Sensenig told the council, compared to as many as 1,000 on North Shattuck and 650 on Solano.

That’s in large part because the district has only a few sites that are attractive candidates for development, planning staff said, such as the parking lot behind the College Avenue Wells Fargo branch or a strip mall anchored by a 7-Eleven. Planning Director Jordan Klein said property owners prefer to develop large and vacant commercial spaces, and are unlikely to evict tenants who are paying regular rents.

Opponents of the plan weren’t reassured — Klein’s comments were met with jeers from audience members, who interrupted speakers at several points Thursday night with booing.

A rendering prepared for a city forum last summer shows a hypothetical example of the kind of project that would be allowed under the new zoning rules. No project has been proposed for the site. Credit: City of Berkeley

A rendering prepared for a city forum last summer shows a hypothetical example of the kind of project that would be allowed under the new zoning rules. No project has been proposed for the site. Credit: City of Berkeley

Will housing hurt or help businesses?

Critics of the rezoning have rallied around the slogan “Save Berkeley Shops,” which many attendees Thursday night wore on stickers or held aloft on signs.

Hunka was one of several North Berkeley and Elmwood merchants who spoke against the plan at Thursday’s meeting, along with owners from Nabolom Bakery, Pegasus Books and the home and garden shop Fern’s Garden. The North Shattuck Association, which represents the area’s businesses, wrote in a letter that the city should permit development “that maintains the integrity and character of our neighborhood.”

Many complained they hadn’t received more direct outreach from the city about the zoning proposal. Vanessa Vichit-Vadakan, a worker-owner at the Cheese Board Collective, said the legendary North Shattuck business is concerned about the potential for the zoning changes to allow a taller apartment building at the vacant site of a former bank branch next door to its pizzeria.

“That might or might not be a good thing,” Vichit-Vadakan said, “I don’t know, because I don’t have that information.”

Supporters of the zoning changes, who included young families and members of “Yes in My Backyard” advocacy groups, rejected the idea that new development would harm the area’s merchants.

“Housing and small businesses cannot and should not be put against each other,” said Brianna Morales, an organizer with the Housing Action Coalition. “More homes means more customers, more stability and more life on our streets.”

Several said adding housing would inject vitality into neighborhoods where few other than longtime homeowners or the very wealthy can afford to live today.

“Solano is dying — it’s the central corridor of a retirement home that only works for privileged old folks,” said Glenn Wolkenfeld, a retired teacher who lives near the avenue. “We need more foot traffic. Because of our anti-zoning history, my adult children can’t live here; we need more housing to lower prices.”

Klein said the city has contracted with a consulting firm to study ways Berkeley can support small businesses during new development, and plans to present those ideas to the City Council before a final vote on the rezoning proposal.

Solano Avenue is one of three major streets that could soon have taller height limits under a rezoning plan. Credit: Kelly Sullivan for Berkeleyside

Solano Avenue is one of three major streets that could soon have taller height limits under a rezoning plan. Credit: Kelly Sullivan for Berkeleyside

Council mostly backs upzoning

Council members broadly backed the idea that the new zoning rules would help, rather than hurt, the areas’ small businesses, and agreed that Berkeley needs to change its land use rules to allow more housing in historically exclusive neighborhoods.

Mayor Adena Ishii and councilmembers Rashi Kesarwani, Terry Taplin, Ben Bartlett and Lunaparra all voiced support for a seven-story height limit, which they said should be a consistent standard for major corridors throughout the city. Taplin and Kesarwani also said they would support an eight-story cap along Shattuck.

“It’s important to have parity across the corridors,” Taplin said, “because I don’t see any utility in reinforcing the segregationist history of exclusionary zoning.”

Taplin and others also said they were open to allowing developers to put apartments, rather than retail space, on the ground floors of some buildings, and weren’t interested in requiring step-backs for upper floors or more-prescriptive design standards for the projects.

Councilmember Mark Humbert, who represents the Elmwood District, was the only one to directly call for scaling back the zoning changes, albeit in a limited way. Humbert said he supported an idea floated by opponents of the plan to rezone only the three properties in the Elmwood that planning staff consider likely candidates for new development — the 7-Eleven, Wells Fargo lot and U.S. Post Office branch at Webster Street — while leaving regulations for other parts of the avenue the same. The city could do the same, he suggested, with properties on nearby Claremont Avenue and southern stretches of Telegraph Avenue that could take on new housing as well.

It was a notable break for Humbert, who was elected three years ago with the support of YIMBY advocates and has consistently backed efforts to encourage more housing in Berkeley. But he argued a tightly focused rezoning would still allow development to proceed without risking the kind of displacement opponents of the changes fear.

“If we can get the exact same projected housing potential or something similar, but take an approach that addresses neighbors’ and merchants’ concerns, why wouldn’t we take that opportunity?” Humbert said. “I think we should work smarter, not harder, when it comes to rezoning, specifically in the Elmwood.”

“*” indicates required fields