After Theris Coats II, (TC to those who knew him), died of a drug overdose in a San Francisco jail in March of this year, his family sought ways to move forward.

His parents filed a lawsuit against the jail staff who had been responsible for his care. His father is working to pass Theris’ Law, legislation that would empower people to put family members into emergency treatment. And Coats’ father and uncle in recent months created a nonprofit, Brothers Against Drug Deaths, to advocate for mental health and addiction support particularly within Black and other underserved communities.

Now, the family is putting on a play.

The idea arose when Coats’ father, Theris Coats Sr., was discussing with Richard Beal — his brother-in-law and the director of recovery services at the Tenderloin Housing Clinic — about the convoluted ins and outs of the system that the family navigated trying to get help for Coats.

Wanting to visualize the issue, Coats Sr. went to his two playwright nieces, Kamika Hebbert and Roz Coats, and asked them for help.

“Where we come from as writers, we have a family history of people who have dealt with drug addiction, mental health challenges,” said Hebbert, Coats’ older cousin and the play’s director.

That history may have helped Coats’ family know who to contact for help in the months leading up to his death. But still, Coats, dealing with mental illness from a young age and addiction, kept slipping through the cracks — he lost his housing, had his leg amputated, and was repeatedly released to the streets on his own.

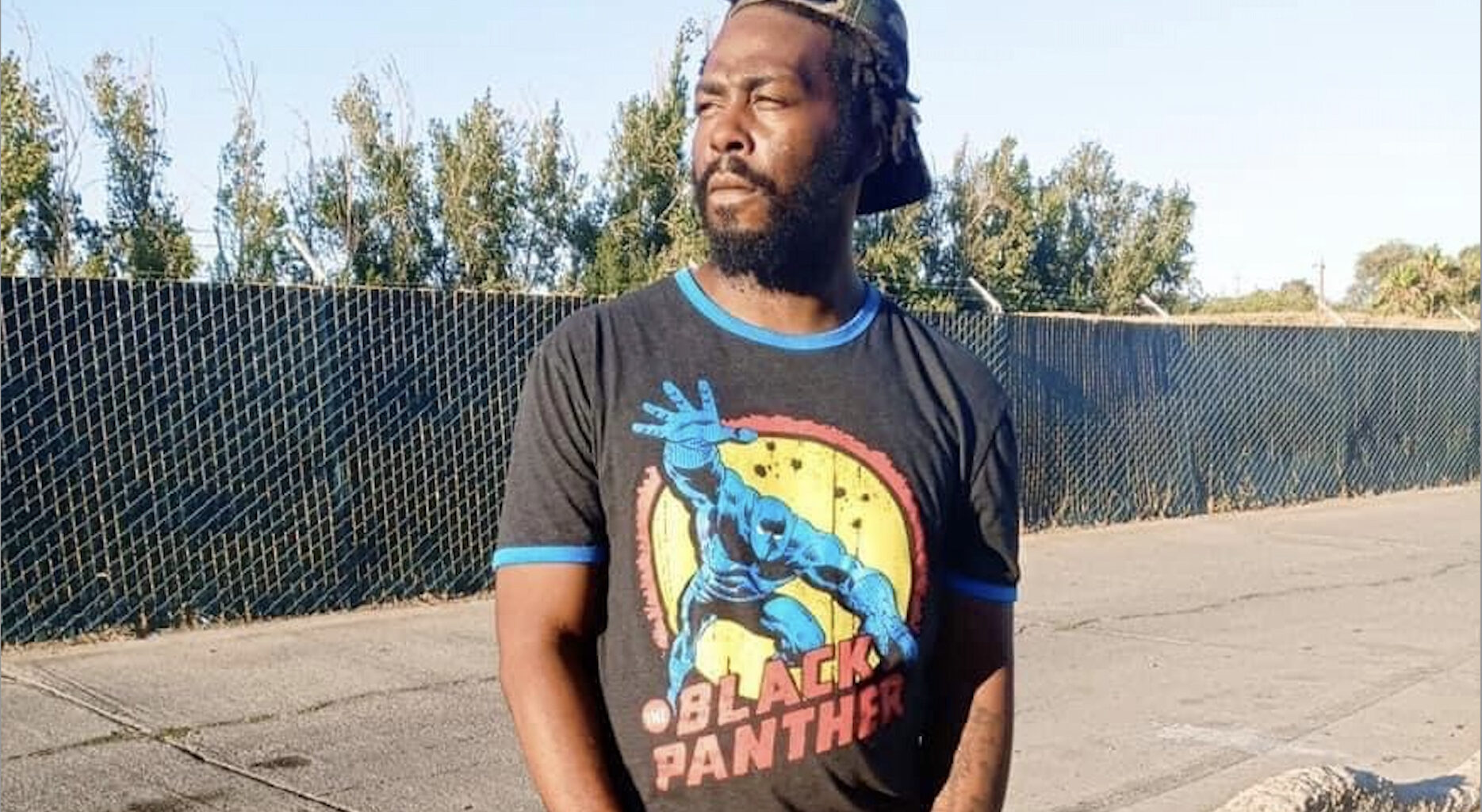

Theris Coats with his father. Photo courtesy of Theris Coats, Sr.

Theris Coats with his father. Photo courtesy of Theris Coats, Sr.

Mission Local first reported on Coats’ death and detailed how Coats Sr. had tried to track him down in the streets of San Francisco.

Coats Sr. worked with a city crisis team, District 6 Supervisor Matt Dorsey’s office, and the police department, trying to trace his son’s path through the streets of San Francisco and place him under conservatorship, which would give him legal authority to make medical decisions for Coats and get him into treatment. But in February, he was released by a judge under a “safe discharge plan” to a treatment center — and promptly disappeared. Soon after, he was arrested, and died the day after he got to jail.

Out of that struggle came “Beyond My Family’s Reach,” which follows two families of different backgrounds trying to help their respective sons get into treatment. It will be performed in two 90-minute showings on Nov. 22 at the Bayview Opera House.

Doing informal research for the play, Coats Sr. began asking random people he encountered for their thoughts, ultimately talking with about 90 people. He quickly realized how common his family’s experience was. Hebbert, the director, said she found the same was true among her 12-person cast.

“They’ve got a brother, they got a sister or a cousin, or somebody out there, and they all are facing the same challenge: ‘How do I how do I get help?’” Coats Sr. said.

The play, he hopes, can help address that question. Beyond themes of mental illness and addiction, he said “it also focuses in on how the system responds … and provides some insight into what people can do.”

Hebbert said that even those with little personal experience in the subject matter will be stirred. “You’ll get sad, you’ll get happy… if it doesn’t hit home, you’ll definitely feel something.”

Both of Coats’ cousins have a passion for theater that they pursue outside of their day jobs. Hebbert also produced an award-winning documentary short, We’ve been Sentenced, about the letters received from loved ones in jails, and Roz Coats has written two novels.

The play received grants from Avenue Greenlight, a philanthropic effort from billionaire Chris Larsen, and political advocacy group Neighbors for a Better San Francisco. Most of the 250 seats at each showing have been reserved.

Roz Coats said she hopes the play will show that people on the streets are not necessarily bad or hopeless, and often have family that wants to help them. She also hopes to start more conversations about mental health — while it was openly discussed in her family, the subject is still “sort of taboo” in the Black community.

“It’s not considered a strength,” she said. When people see a family member using drugs, they may miss signs that it’s an outgrowth of existing mental illness.

While they were unable to help Coats, his family wants to ensure others learn about the resources available to avoid deaths like his.

“Not only can we share information on the street, but we can do something on a bigger scale, where more people can get the message,” Coats Sr. said, “Not just about my son dying, but about all of the people that’s dying.”