John Beam’s death Friday after an on-campus shooting at Laney College left an unmistakable void in Oakland.

For the first time in 43 years, a generation of the city’s young athletes couldn’t seek out the legendary coach’s advice. But if you called his cell phone and waited for his voicemail greeting, you could still hear his raspy voice deliver one of his signature credos: “Remember that I believe in you, so that you can believe in yourself.”

Those 13 words offer a fitting reminder of Beam’s greatest legacy. Though he was one of the winningest high-school and community-college coaches in Bay Area history, many of his most meaningful victories came off the field. For over four decades, Beam spurned more high-profile – and, potentially, more lucrative – opportunities elsewhere to stay in Oakland, where his ability to affect change was unquestioned.

“If you’re from the Bay and have anything to do with football, you know John Beam,” Riordan High School football coach Adhir Ravipati said. “He gave so much back.”

John Beam, drenched after Skyline High School beat Fremont High School 27-18 during the 2000 Silver Bowl, was an Oakland football icon, coaching at Skyline and Laney College. (John O’Hara/S.F. Chronicle)

In 2004, after transforming Oakland’s Skyline High School into a local football powerhouse, Beam joined Laney and outdid himself. In addition to leading the oft-overlooked commuter school to a national community college championship in 2018, he sent 20 players to the NFL and moonlighted as the Eagles’ athletic director.

Along the way, Beam helped thousands of young men gain self-esteem, improve their grades and achieve the ultimate goal for community college students: a bachelor’s degree somewhere, anywhere, and a chance at a better life. For those who knew him best, that’s what made Friday’s news so stunning. Former Skyline football player Cedric Irving Jr. is in police custody for allegedly shooting Beam in the head a day earlier inside Laney’s fieldhouse.

Beam was pronounced dead Friday morning, less than 24 hours after arriving at Highland Hospital in critical condition. He was 66. As of Saturday, details from Thursday’s on-campus incident remained sparse, with Oakland police insisting Irving didn’t go to the campus with the intent to shoot Beam.

What’s clear: For many Oaklanders, Beam’s death represents yet another devastating blow for a city that desperately needs some good news after all three major pro sports teams bolted town and a corruption scandal rocked city hall. Just a day before Beam was shot in his office, there was a separate shooting at Skyline High, where Beam once coached and taught for 22 years. A Skyline student was wounded during the incident; two juveniles were detained.

“How much more can Oakland take?” said former Bishop O’Dowd Football Coach Paul Perenon, who lives near the Beam family in the Oakland hills. “It’s just gut punch after gut punch. And it’s attacking our soul.”

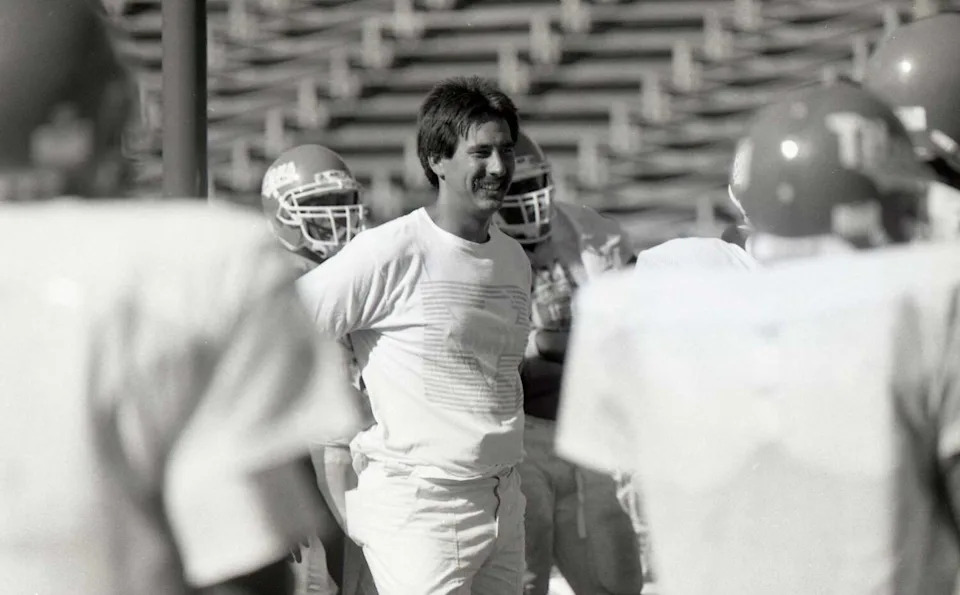

Skyline High School football coach John Beam in 1989. He coached at the Oakland school for 22 years. (Deanne Fitzmaurice/S.F. Chronicle)

Mayor Barbara Lee called Beam a “giant.” City councilmember Ken Houston said he was “a legend in our city.” Bishop O’Dowd boys basketball coach Lou Richie, a close friend of Beam’s, described him as the greatest advocate for Oakland kids in the past 40 years.

It wasn’t so much that Beam helped hundreds of Skyline and Laney football players land full-ride college scholarships. For many young Oakland athletes, he was the first adult to make them believe a college education was even possible.

At both Skyline and Laney, Beam curated academic systems that later became models for other athletic programs throughout the Bay Area. The detailed guides covered everything from how to facilitate study halls to how to find players extra support to how to align practice schedules with class times.

Beam was also instrumental in expanding Oakland’s youth football programs. Each year, high school coaches looked forward to taking their teams to his summer camps, where he’d provide hands-on, individual instruction to players of all skill levels.

Coach John Beam, center, and Skyline High School football players Harrison Smith (2), Davis Young (32) (hidden) and Terry Johnson (28) celebrate after beating Fremont High School 27-18 during the Silver Bowl in 2000. (John O’Hara/S.F. Chronicle)

Among the many people who considered him a mentor are dozens of coaches now working in Oakland public schools, Bay Area high schools and local community organizations. Perhaps the most notable is C.J. Anderson, whose seven-year NFL career included 3,497 rushing yards, a Pro Bowl appearance and a Super Bowl win. He’s now the head football coach at Benicia High School, just a 10-minute drive from his childhood home in Vallejo.

In February 2016, two days before scoring a touchdown in front of a Levi’s Stadium crowd in the Denver Broncos’ Super Bowl 50 victory over the Carolina Panthers, Anderson invited Beam to media festivities in San Jose. After embracing Beam while dozens of cameras snapped photos, Anderson pointed back toward the coach.

“That’s the type of family I have,” Anderson told reporters. “That’s the kind of people I’ve had pushing me in my life.”

Like many of Beam’s other former Laney players, Anderson was a lightly touted recruit raised by a single mother in the Bay Area. As a quarterback/running back at Vallejo’s Bethel High School, he ran for nearly 4,000 yards, only for poor grades to land him at an Oakland community college with no on-campus housing and meager facilities.

For two years, Anderson awoke in his Vallejo home at 3:45 a.m. so he could catch BART to Oakland and make the Laney Eagles’ 6:30 a.m. weightlifting sessions. If he was ever late, he didn’t have to worry about getting cussed out by Beam, who understood the challenges each of his players overcame just to attend school.

More lover than yeller, he was the quintessential “players’ coach” – the kind of leader who made a point to know his players on a personal level. That softer approach endeared Beam to fans of Netflix’s “Last Chance U.”

After spending the documentary series’ first four seasons with expletive-spewing coaches in Mississippi and Kansas, series creators chose to focus the fifth season on Laney, which, at the time, was fresh off a national title. By giving a 30-person film crew complete behind-the-scenes access for an entire season, Beam allowed a national TV audience to see why so many of his players considered him a father figure.

Viewers watched as he joined his wife on morning walks around their neighborhood, asked a social worker to help athletes apply for food stamps and counseled players as they navigated situations far more serious than wins and losses.

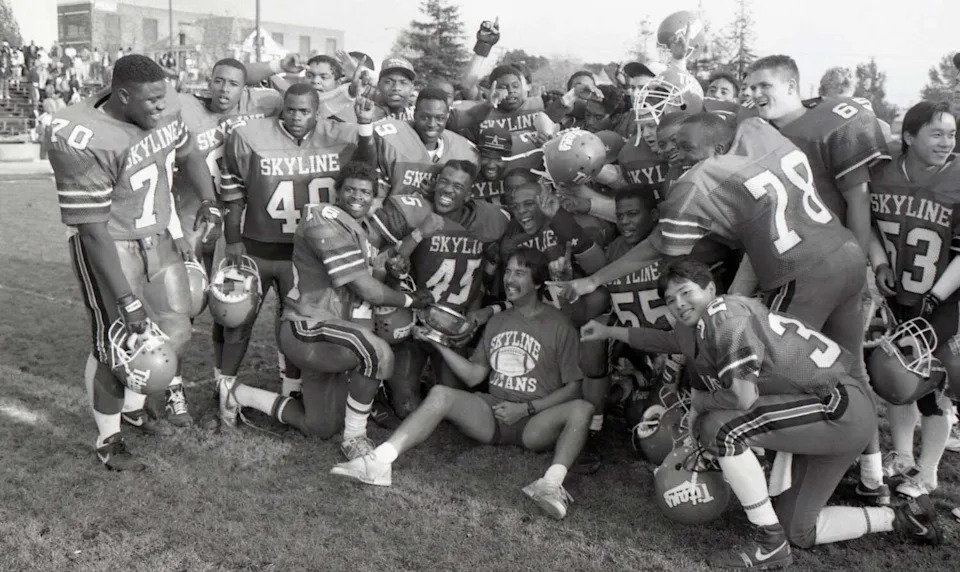

Coach John Beam, center bottom, and the Skyline High School football team pose together after beating Oakland High School 19-0 for a championship in 1989. (John O’Hara/S.F. Chronicle)

The season’s most memorable storyline centered on wide receiver-turned-emergency quarterback Dior Walker-Scott, who juggled a work-study job, a full course load, football responsibilities and a part-time gig at Wingstop. Most nights, he slept under a pile of blankets in his SUV.

In one scene, Walker-Scott left practice with a panic attack. Instead of barking at his starting quarterback for cutting drills, Beam had Walker-Scott speak to his wife, who talked him through breathing exercises over the phone.

Football players at Campolindo High School in Moraga became so captivated by that season that their head coach, Kevin Macy, organized team watch parties. “Honestly, that ‘Last Chance U’ series did John and Oakland proud,” Macy said. “You got to see all the people he impacted.”

Well, not all the people. Since news of the shooting went national Thursday, dozens of Beam’s former athletes, including several NFL players, have posted tributes on social media.

John Beam, Laney College athletic director and former head football coach, watches from the sidelines during the third quarter of a North Coast Section Division 3-AA high school football championship between Amador Valley and McClymonds in December 2024, at McClymonds High School in Oakland. (D. Ross Cameron/Bay Area News Group)

Next to an Instagram photo of current New Orleans Saints cornerback Rejzohn Wright with Beam, Wright had a six-word caption: “You mean the world to me.” Under a slideshow of pictures from their time together at Laney, Walker-Scott thanked Beam for helping a “kid who was broken and had no confidence” believe in himself again.

“That (‘I-believe-in-you’) saying was something he started putting out regularly,” Chris Kyriacou, a former Skyline assistant under Beam, said of Beam’s voicemail greeting. “However, he has been living that for the 40 years that I’ve known him.”

This article originally published at John Beam gave Oakland hope. The ‘Last Chance U’ coach’s death is a ‘gut punch’ to the city.