Student Michelle Ramirez is using computational tools for her Ladino language project, under the mentorship of Carlos Yebra López, assistant professor of modern languages and literatures.

Student Michelle Ramirez is using computational tools for her Ladino language project, under the mentorship of Carlos Yebra López, assistant professor of modern languages and literatures.

Humanities student Michelle Ramirez is using supercomputing and data tools to preserve the centuries-old Ladino language — with the help of a chatbot named “Estreya Perez.”

Ladino, also called Judeo-Spanish, is an endangered language originally spoken by Jewish people from the Iberian Peninsula who were exiled in 1492.

It is estimated that about 50,000 people — mostly older generations —speak Ladino today, said Ramirez’s faculty adviser Carlos Yebra López, assistant professor of modern languages and literatures.

Ramirez participated in the Titan Supercomputing Center’s student research program and learned about integrating high-powered computing, data science and artificial intelligence into her project to revitalize vanishing languages.

“By stepping into high-performance computing, I hope to show that students from the humanities belong in the world of data just as much as anyone else,” said Ramirez, a double major in Spanish and liberal studies.

The Titan Supercomputing Center is expanding the role of computational tools at CSUF and is a resource to students and faculty as they explore high-powered computing and data science, said Jessica Jaynes, center director and professor of mathematics.

“The summer research program allowed students across campus to work with their faculty mentors on cutting-edge computational research projects,” added Andrew Petit, the center’s associate director and associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry.

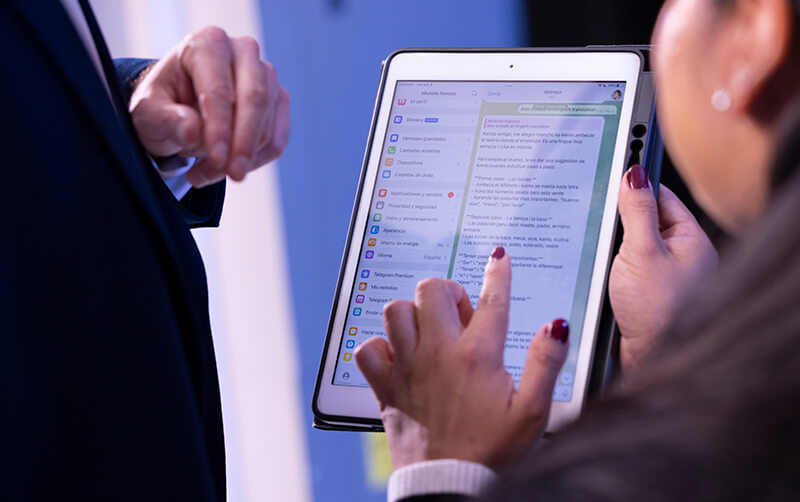

Michelle Ramirez and her faculty research adviser Carlos Yebra López test the chatbot named ‘Estreya Perez’ to preserve the Ladino language.

Michelle Ramirez and her faculty research adviser Carlos Yebra López test the chatbot named ‘Estreya Perez’ to preserve the Ladino language.

Yebra López, a Ladino cultural expert, turned to technology to develop the first AI-powered Ladino chatbot.

He and his collaborators, computational linguist Alp Oktem and romance language expert Alejandro Acero Ayuda, launched the “Estreyika” project, which translates to “little star” in efforts to guide future generations of Ladino learners.

“Estreyika stands as a model for using supercomputing and Al to preserve endangered languages worldwide,” Yebra López said. “By intersecting technology, language, culture and education, the project keeps Ladino alive in the digital age.”

Ramirez wanted to be part of the project, “Revitalizing Endangered Languages With AI: Estreyika, an Interactive Ladino Teacher,” because of the impact the chatbot could make on the Ladino-speaking community.

“When I learned how technology can be used for language revitalization, I realized there’s a need for cultural and linguistic experts who can serve as mediators in training these models,” said Ramirez, whose career goal is to become a state certified interpreter.

Yebra López said the Ladino-speaking chatbot is trained with religious and cultural references. “Estreya Perez” engages in conversation with prompts in English and Spanish, and replies to questions about daily life and community dynamics.

The chatbot is also coded with specific grammatical rules and adjustments that reflect Ladino’s linguistic particularities.

“I like to think of Estreya Perez as a Ladino teacher that fits in your pocket,” Ramirez said. “She draws on conversational capabilities and is accessible through a user-friendly app.”

Yebra López and his students are working on refining the chatbot for system optimization. They analyze chatlogs to understand how Estreyika responds to users, identify and correct grammatical errors and modify code to fix bugs or glitches that affect performance.

“By combining computational analysis with cultural and linguistic expertise, we’re able to shape Estreyika into more than just a chatbot,” Ramirez said.

“We hope it becomes a model on how technology and the humanities can work together to preserve endangered languages with even more limited digital footprints. Most importantly, computation can be a powerful tool for preservation and accessibility.”