San Francisco supervisors voted Monday to table many of the proposed amendments to the mayor’s housing upzoning plan, and instead approved only those that California state officials supported.

The plan, which allows housing developers to build taller, denser buildings throughout the city’s north and west, has generated concern that developers will displace tenants and businesses to build taller, more profitable buildings.

But, the state is requiring San Francisco to create capacity for 36,000 additional units. As YIMBYs in San Francisco and the state legislature see it, building a lot more housing is needed to address the city’s affordability crisis, and rezoning is a necessary step.

If the city fails to rezone, it may face the “builder’s remedy,” where it loses control of its ability to approve or reject new housing developments, regardless of where they are and their height and density.

A Sept. 9 letter from state housing authorities warned San Francisco against “introducing potential constraints on development.” While the plan was currently compliant, they said, amendments would need to more or less preserve the new capacity created.

At the Land Use Committee meeting, the planning department explained what officials at the California Department of Housing and Community Development had communicated about each amendment — plus an estimate of how much the amendment would change capacity.

These are some of the amendments that the Land Use Committee accepted:

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Those amendments were accepted because the formula that the planning department used to calculate capacity already assumed that those sites would not be developed.

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Illustration by Neil Ballard

This amendment was acceptable because it provided incentives, not constraints.

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Supervisor Sherrill’s exempted the Safeway in the Marina, Ghirardelli Square, and a senior living facility on Geary, but increased heights on Van Ness Avenue and Pine Street to make up the difference.

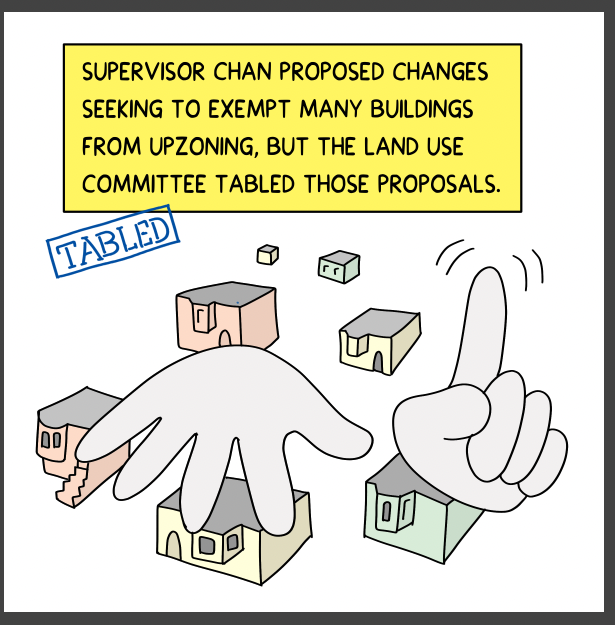

But some amendments were tabled:

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Illustration by Neil Ballard

Chan’s amendments included: removing all existing housing from the plan, lowering heights on commercial corridors within her district, removing areas along the coast from the plan, exempting historic districts, removing provisions that allowed developers to build more units per site, and more.

But each of those changes had the potential to decrease the capacity of the plan by thousands of units, the planning department said, and the amendments were not accompanied by height increases in other areas.

Also tabled was Supervisor Chyanne Chen’s amendment to remove the city’s “priority equity geographies,” areas that have larger proportions of low income people and people of color.

The planning department said that change would decrease capacity by several thousand units — too much for the state. Plus, the planning department added, many of the blocks included in the plan are relatively better off — they are “medium resourced.” Melgar, for example, said that several golf courses in her district were included in the priority equity geographies.

For the tabled amendments, it is likely the end of the road. Theoretically, they could still be integrated when the plan is finally considered at the Land Use Committee meeting on Dec. 1, or when the plan is voted on at the Board of Supervisors meeting on Dec. 2. But unless the sponsor can find a way to offset the number of potential units lost under their amendments, they are unlikely to succeed.

Mayor Daniel Lurie, who sponsored the legislation, will likely have enough votes to pass the measure when it goes before the full Board.

But at the board meeting, Chan continued to push for her changes, calling them “non-negotiable.”

“As elected leaders, we cannot simply agree to demolish San Francisco for the sake of meeting a state mandate legislated by a simple-minded legislature based on unproven housing ideology,” Chan said at the hearing, to loud cheers.

But, failing to meet the state mandate could have bad consequences, Supervisor Bilal Mahmood pointed out. “If we don’t meet the estimates of capacity, then builder’s remedy takes effect and we lose local control,” he said, also bringing up the fact that the city could lose millions in state funding if the zoning plan does not go through.

“The fact that the proposed amendments that we’ve been working on for so long to be rejected today, is a moment for San Franciscans to recognize that we must make some change in this city,” Chan said. “If we can’t do that with our elected leaders, then we must put that power back to the people and make that change.”