By Lizeth Tello and Jada Portillo

A growing number of Black residents, many of them elderly, are living alone in the Sacramento region.

In 2024, almost 23,000 Black residents in the Sacramento region lived alone, according to new United States Census Bureau data. The number of Black residents living alone in the area has gone up by about 38% in the past decade.

It is estimated about half of single-person Black households in the region are aged 60 or older.

According to the Institute for Family Studies, the rise in people living alone correlates with a rise in loneliness. Older residents can be at greater risk of loneliness due to childlessness, divorce, deceased family, spatial isolation, spousal deaths, or lack of family time due to busy schedules.

With a rise in loneliness, health issues are more prone to develop as well, especially in older individuals.

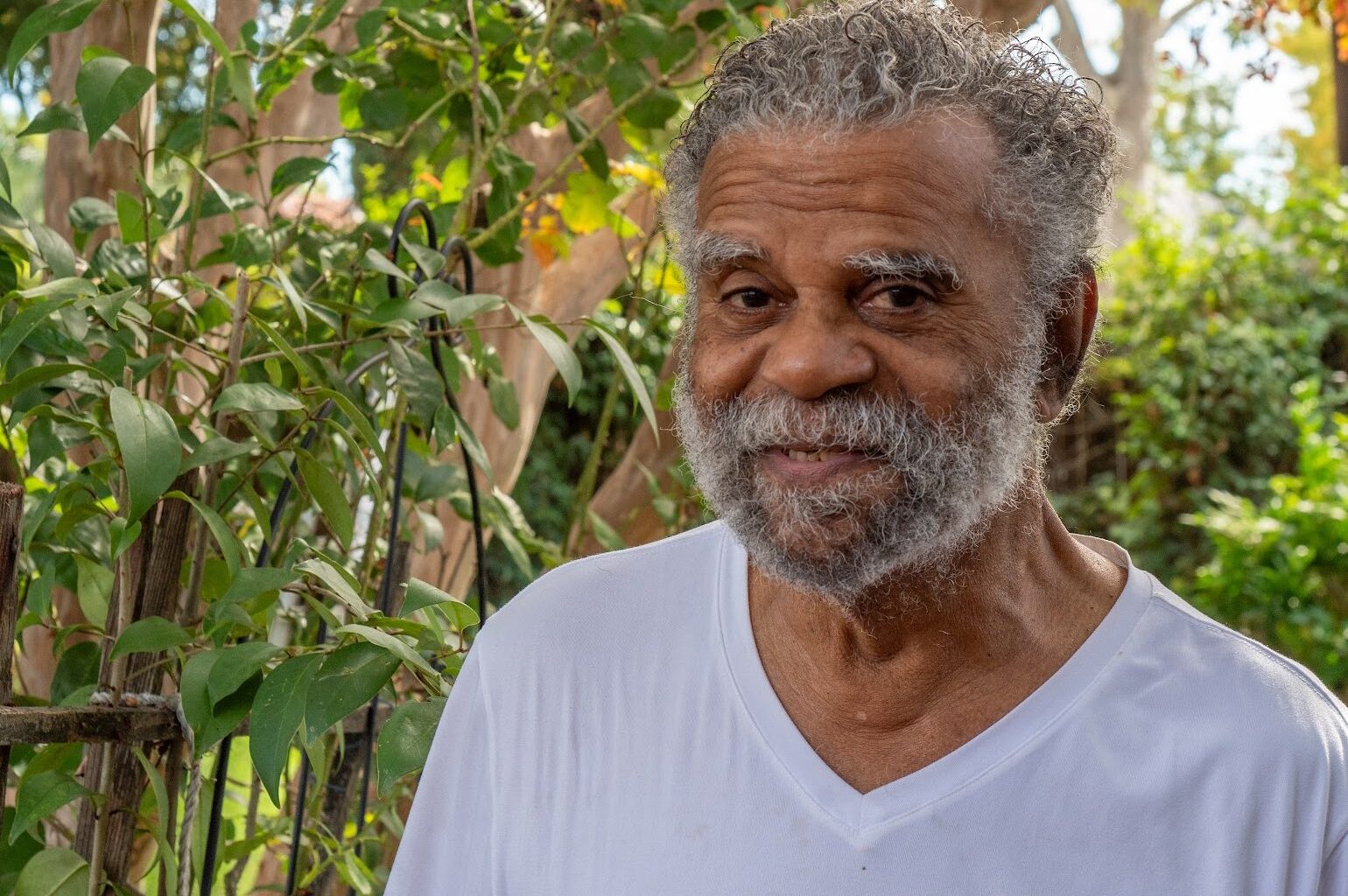

“I’ve been alone my whole life,” says 85-year-old Robbin Ware, a longtime Oak Park resident and former president of the Sacramento NAACP. He has lived alone for several decades.

Nate Woo, a behavioral scientist and assistant professor at Sacramento State, has studied communication and loneliness since 2015. Woo says that when an individual is involuntarily socially isolated, no matter the age, it can lead to an increased risk of depression, anxiety and an overall decline in mental health.

“As a social species, we have this innate need to belong,” Woo says. “And when those belongingness needs are taken away and stripped away from us, there are significant mental and physical health outcomes.”

According to a 2020 study from the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, social isolation plays an important role in mortality patterns, as well as contributing to several negative physical health symptoms like an increased risk of diabetes, arthritis, emphysema, liver disease, kidney disease and chronic inflammation. Social isolation also tended to result in higher mortality rates.

Based on the study, rates of illness were especially high within the African American community, with Black individuals who were subjectively lonely experiencing 1.41 times the risk of depression and 1.31 times the risk of serious psychological distress.

For Ware, solitude is nothing new — and nothing to fear. Yet, perhaps unlike many of the roughly 23,000 Black residents in Sacramento who live alone, he says his life experiences have prepared him to embrace solitude rather than be consumed by it.

“I’ve been lucky,” Ware says, reflecting on the friends and community ties that have sustained him. Over the years, he has formed lasting bonds with people from all walks of life, including a close connection to Sacramento’s Jewish community. “I don’t know why that is,” he says with a smile, “other than the fact that I love them.”

Ware says he feels lonely only “once in a great, great while.” His contentment, he says, comes from a lifetime of learning to be on his own. As a child, he spent long stretches separated from family, shuttled between institutions and his father’s home. In school and later at Yuba College, he often was one of the few Black students in overwhelmingly white spaces. “My life, my trajectory, has prepared me to live alone,” he says. “I’ve always had to find my own way.”

Ware once was married and has a son he sees periodically. He and his wife divorced in the late 1980s, a transition that deepened his independence but never erased his love for people.

“I never felt alone because I was a natural for people,” he says. “I fell in love with people, and they fell in love with me.”

Even now, when moments of isolation arise, Ware reaches for the phone. “I make a call — talk about politics, economics, whatever’s going on in the world,” he says. Living with a mental health-related disability also has shaped how he views connection and resilience. “It’s part of my makeup,” he says, describing how his friendships help keep him grounded. “If it weren’t for people, I wouldn’t have a damn thing. Without them, I’d probably be in the street.”

For Ware, companionship, not constant company, is what keeps him steady. His life, marked by both hardship and enduring connection, underscores that loneliness doesn’t always come from being alone.

“As a society, the worst thing that we have deemed that we could do to one another, short of the death penalty, is social isolation, solitary confinement,” Woo says. “It is the worst punishment that we could inflict on a fellow group or member.”

Woo says loneliness is subjective. A person can have one, five or 50 friends and still feel lonely; it all depends on each person’s subjective perception of their own loneliness. Those who do not feel subjectively lonely are less likely to experience the symptoms and increased risks associated with loneliness.

Janet Hillis, an 86-year-old African American widow from San Francisco, had moved to Sacramento about seven years ago. About three years ago, her 67-year-old son, Dwight Jackson, moved in with her to take care of her after she fell ill with cancer. Prior to his arrival, she spent about four years living alone.

“So, he thinks I need to be out and have people around, but that’s not true,” Hillis said before she died Oct. 9. “Cause I like crossword puzzles. I like watching TV. I like listening to music. So, that’s my company.”

Hillis said she did not feel lonely during her time alone and was actually happy to be so. She said she received visits from her grandchildren almost every day, at least until Jackson moved in.

Jackson says that though his mother claimed to not care, none of the aspects of her social life in Sacramento would have happened without his intervention. Before he moved in, he says, Hillis’ nutrition was not up to par, she got no exercise and she always stayed home.

“I have to facilitate these things so that they actually happen, cause then there wouldn’t be any socialization,” Jackson says. “But as she said, she don’t care, which is — that’s a problem, but she doesn’t recognize it as a problem.”

Jackson introduced Hillis to the Ethel Hart Senior Center in Sacramento to get her to be more active and social. They both regularly visited before her passing. Hillis said she appreciated all that her son had done for her and was glad to be introduced to the senior center, where she got regular exercise and liked to play bingo with the other seniors.

Such centers exemplify the many resources seniors can use to reduce their likelihood of feeling lonely.

“I would say the majority do come for the social interaction,” says Jeremey Hao, a program coordinator at the center. “Just because we have so many people that come here every day, and that’s a great way to connect with others.”

Hao says seniors have approached him expressing gratitude for what the center has done to improve their lives.

Other programs, such as Sacramento County’s In Home Supportive Services, also help seniors by ensuring they are not isolated and that they get the help they need to remain happy and healthy. According to Sacramento County, senior isolation is a problem within the region, especially considering the growing trend in older adults.

The Agency on Aging Area 4 worked on “The Dual Challenge” to investigate how the aging of baby boomers may affect counties such as Sacramento, Nevada, Placer, Sierra, Sutter, Yolo and Yuba.

Based on the report, by 2040 more than 800,000 people aged 60 and older are projected to live in these regions.

Will Tift, the agency’s planning administrator, says greater cultural awareness and recognition are needed for people to address the growing population of older residents. “What we need to move forward is a more positive, more empowering message,” he says.

In 2019, the Master Plan for Aging was created by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s executive order. The California Department of Aging received $50 million from the 2023-24 State Budget General Fund to help community partners meet the behavioral needs of older adults, such as isolation. To support adult behavioral health, about $15 million was given for statewide support.

“It definitely is a societal problem,” Woo says. “And it’s going to require some societal solutions.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was produced by Phillip Reese’s Sac State journalism students for The OBSERVER. OBSERVER Staff Writer Robert J. Hansen contributed to this story.

Related